America’s History: Printed Page 707

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 641

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 623

Erosion of Labor Rights

African Americans were not the only ones who faced challenges to their hard-won gains. The war effort, overseen by a Democratic administration sympathetic to labor, had temporarily increased the size and power of labor unions. The National War Labor Board had instituted a series of prolabor measures, including recognition of workers’ right to organize. Membership in the American Federation of Labor (AFL) grew by a third during World War I, reaching more than 3 million by war’s end, and continued to climb afterward. Workers’ expectations also rose as the war economy brought higher pay and better working conditions.

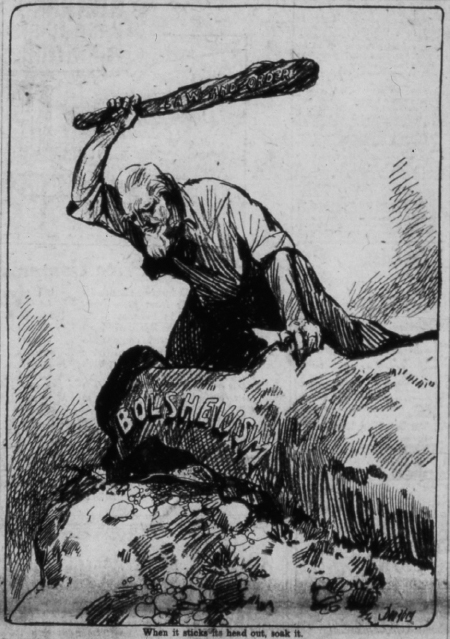

But when workers tried to maintain these standards after the war, employers cut wages and rooted out unions, prompting massive confrontations. In 1919, more than four million wage laborers — one in every five — went on strike, a proportion never since equaled. A walkout of shipyard workers in Seattle sparked a general strike that shut down the city. Another strike disrupted the steel industry, as 350,000 workers demanded union recognition and an end to twelve-hour shifts. Elbert H. Gary, head of United States Steel Corporation, refused to negotiate; he hired Mexican and African American replacements and broke the strike. Meanwhile, business leaders in rising industries, such as automobile manufacturing, resisted unions, creating more and more nonunionized jobs.

Public employees fared no better. Late in 1919, Boston’s police force demanded a union and went on strike to get it. Massachusetts governor Calvin Coolidge won national fame by declaring, “There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, anytime.” Coolidge fired the entire police force; the strike failed. A majority of the public supported the governor. Republicans rewarded Coolidge by nominating him for the vice-presidency in 1920.

Antilabor decisions by the Supreme Court were an additional key factor in unions’ decline. In Coronado Coal Company v. United Mine Workers (1925), the Court ruled that a striking union could be penalized for illegal restraint of trade. The Court also struck down federal legislation regulating child labor; in Adkins v. Children’s Hospital (1923), it voided a minimum wage for women workers in the District of Columbia, reversing many of the gains that had been achieved through the groundbreaking decision in Muller v. Oregon. Such decisions, along with aggressive antiunion campaigns, caused membership in labor unions to fall from 5.1 million in 1920 to 3.6 million in 1929 — just 10 percent of the nonagricultural workforce.

In place of unions, the 1920s marked the heyday of welfare capitalism, a system of labor relations that stressed management’s responsibility for employees’ well-being. Automaker Henry Ford, among others, pioneered this system before World War I, famously paying $5 a day. Ford also offered a profit-sharing plan to employees who met the standards of its Social Department, which investigated to ensure that workers’ private lives met the company’s moral standards. At a time when government unemployment compensation and Social Security did not exist, General Electric and U.S. Steel provided health insurance and old-age pensions. Other employers, like Chicago’s Western Electric Company, built athletic facilities and selectively offered paid vacations. Employers hoped this would build a loyal workforce and head off labor unrest. But such plans covered only about 5 percent of the industrial workforce. Facing new financial pressures in the 1920s, even Henry Ford cut back his $5 day. In the tangible benefits it offered workers, welfare capitalism had serious limitations.