America’s History: Printed Page 745

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 676

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 656

The New Deal Under Attack

As New Dealers waited anxiously for the economy to revive, Roosevelt turned his attention to the reform of Wall Street, where reckless speculation and overleveraged buying of stocks had helped trigger the financial panic of 1929. In 1934, Congress established the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to regulate the stock market. The commission had broad powers to determine how stocks and bonds were sold to the public, to set rules for margin (credit) transactions, and to prevent stock sales by those with inside information about corporate plans. The Banking Act of 1935 authorized the president to appoint a new Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, placing control of interest rates and other money-market policies in a federal agency rather than in the hands of private bankers.

Critics on the Right Such measures exposed the New Deal to attack from economic conservatives — also known as the political right. A man of wealth, Roosevelt saw himself as the savior of American capitalism, declaring simply, “To preserve we had to reform.” Many bankers and business executives disagreed. To them, FDR became “That Man,” a traitor to his class. In 1934, Republican business leaders joined with conservative Democrats in the Liberty League to fight what they called the “reckless spending” and “socialist” reforms of the New Deal. Herbert Hoover condemned the NRA as a “state-controlled or state-directed social or economic system.” That, declared the former president, was “tyranny, not liberalism.”

The National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) was even more important than the Liberty League in opposing the New Deal, as the NAM’s influence stretched far into the post-World War II decades. Sparked by a new generation of business leaders who believed that a publicity campaign was needed to “serve the purposes of business salvation,” the NAM produced radio programs, motion pictures, billboards, and direct mail in the late 1930s. In response to what many conservatives perceived as Roosevelt’s antibusiness policies, the NAM promoted free enterprise and unfettered capitalism. After World War II, the NAM emerged as a staunch critic of liberalism and forged alliances with influential conservative politicians such as Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan.

For its part, the Supreme Court repudiated several cornerstones of the early New Deal. In May 1935, in Schechter v. United States, the Court unanimously ruled the National Industrial Recovery Act unconstitutional because it delegated Congress’s lawmaking power to the executive branch and extended federal authority to intrastate (in contrast to interstate) commerce. Roosevelt protested but watched helplessly as the Court struck down more New Deal legislation: the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the Railroad Retirement Act, and a debt-relief law known as the Frazier-Lemke Act.

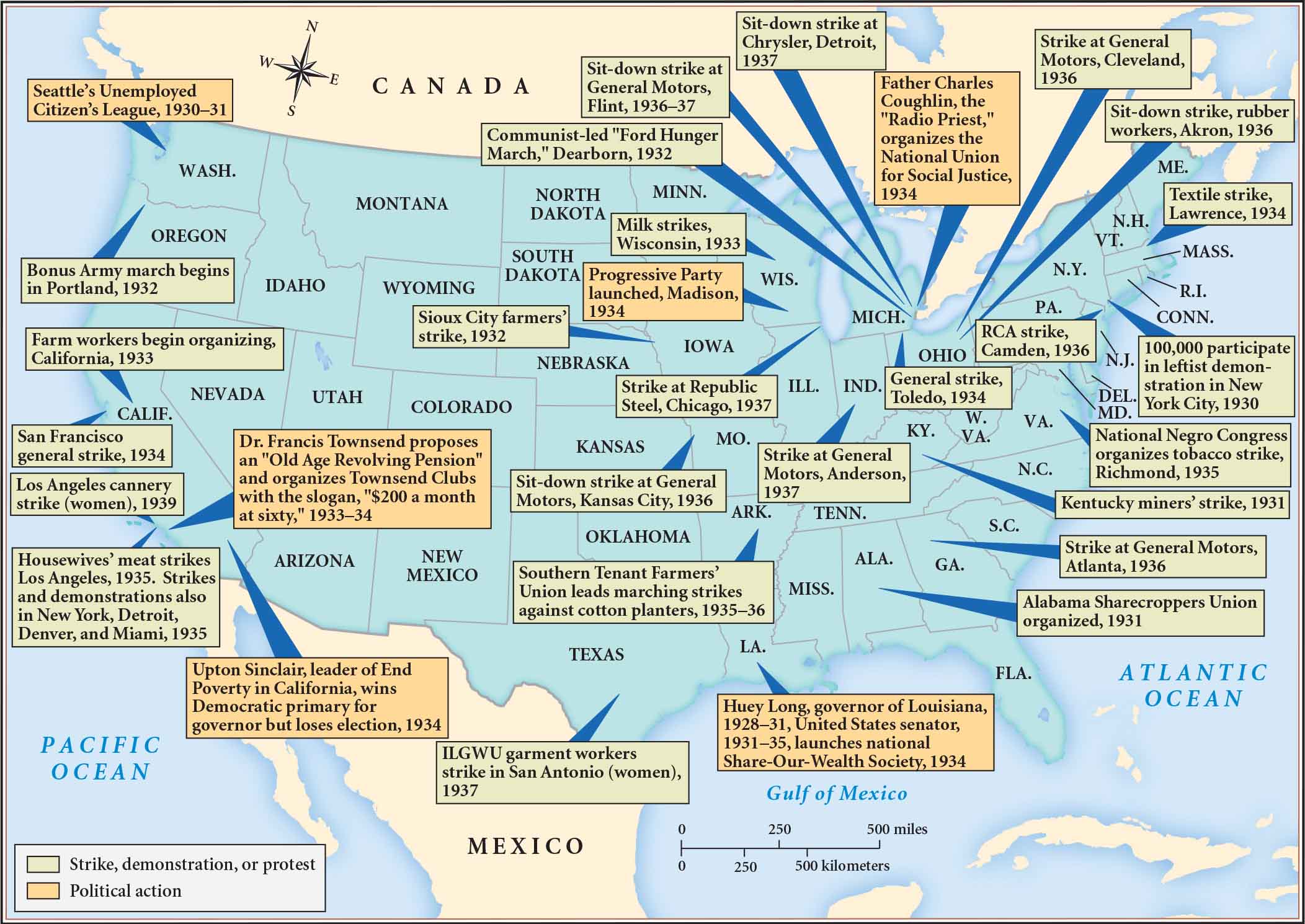

Critics on the Populist Left If business leaders and the Supreme Court thought that the New Deal had gone too far, other Americans believed it had not gone far enough. Among these were public figures who, in the tradition of American populism, sought to place government on the side of ordinary citizens against corporations and the wealthy. Francis Townsend, a doctor from Long Beach, California, spoke for the nation’s elderly, most of whom had no pensions and feared poverty. In 1933, Townsend proposed the Old Age Revolving Pension Plan, which would give $200 a month (about $3,300 today) to citizens over the age of sixty. To receive payments, the elderly would have to retire and open their positions to younger workers. Townsend Clubs sprang up across the country in support of the Townsend Plan, mobilizing mass support for old-age pensions.

The most direct political threat to Roosevelt came from Louisiana senator Huey Long. As the Democratic governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932, the flamboyant Long had achieved stunning popularity. He increased taxes on corporations, lowered the utility bills of consumers, and built new highways, hospitals, and schools. To push through these measures, Long seized almost dictatorial control of the state government. Now a U.S. senator, Long broke with the New Deal in 1934 and, like Townsend, established a national movement. According to his Share Our Wealth Society, inequalities in the distribution of wealth prohibited millions of ordinary families from buying goods, which kept factories humming. Long’s society advocated a tax of 100 percent on all income over $1 million and on all inheritances over $5 million. He hoped that this populist program would carry him into the White House.

That prospect encouraged conservatives, who hoped that a split between New Dealers and populist reformers might return the Republican Party, and its ideology of limited government and free enterprise, to political power. In fact, Roosevelt feared that Townsend and Long, along with the popular “radio priest,” Father Charles Coughlin, might join forces to form a third party. He had to respond or risk the political unity of the country’s liberal forces (Map 23.3).

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

How did critics on the right and left represent different kinds of challenges to Roosevelt and the New Deal?