America’s History: Printed Page 736

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 666

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 648

Enter Herbert Hoover

President Herbert Hoover and Congress responded to the downturn by drawing on two powerful American traditions. The first was the belief that economic outcomes were the product of individual character. People’s fate was in their own hands, and success went to those who deserved it. The second tradition held that through voluntary action, the business community could right itself and recover from economic downturns without relying on government assistance. Following these principles, Hoover asked Americans to tighten their belts and work hard. After the stock market crash, he cut federal taxes in an attempt to boost private spending and corporate investment. “Any lack of confidence in the economic future or the strength of business in the United States is foolish,” Hoover assured the country in late 1929. Treasury secretary Andrew Mellon suggested that the downturn would help Americans “work harder” and “live a more moral life.”

While many factors caused the Great Depression, Hoover’s adherence to the gold standard was a major reason for its length and severity in the United States. Faced with economic catastrophe, both Britain and Germany abandoned the gold standard in 1931; when they did so, their economies recovered modestly. But the Hoover administration feared that such a move would weaken the value of the dollar. In reality, an inflexible money supply discouraged investment and therefore prevented growth. The Roosevelt administration would ultimately remove the United States from the burdens of the gold standard in 1933. By that time, however, the crisis had achieved catastrophic dimensions. Billions had been lost in business and bank failures, and the economy had stalled completely.

Along with their adherence to the gold standard, the Hoover administration and many congressional Republicans believed in another piece of economic orthodoxy that had protected American manufacturing in good economic times but that proved damaging during the downturn: high tariffs (taxes on imported goods designed to encourage American manufacturing). In 1930, Republicans enacted the Smoot-Hawley Tariff. Despite receiving a letter from more than a thousand economists urging him to veto it, Hoover approved the legislation. What served American interests in earlier eras now confounded them. Smoot-Hawley triggered retaliatory tariffs in other countries, which further hindered global trade and led to greater economic contraction throughout the industrialized world.

The president recognized that individual initiative, voluntarism, and high tariffs might not be enough, given the depth of the crisis, so he proposed government action as well. He called on state and local governments to provide jobs by investing in public projects. And in 1931, he secured an unprecedented increase of $700 million in federal spending for public works. Hoover’s most innovative program was the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), which provided federal loans to railroads, banks, and other businesses. But the RFC lent money too cautiously, and by the end of 1932, after a year in operation, it had loaned out only 20 percent of its $1.5 billion in funds. Like most federal initiatives under Hoover, the RFC was not nearly aggressive enough given the severity of the depression. With federal officials fearing budget deficits and reluctant to interfere with the private market, caution was the order of the day.

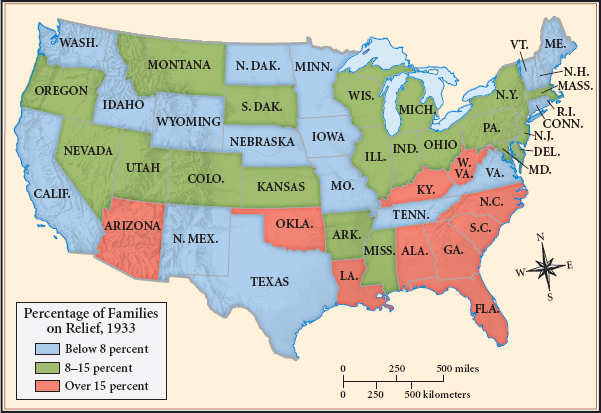

Few chief executives could have survived the downward economic spiral of 1929–1932, but Hoover’s reluctance to break with the philosophy of limited government and his insistence that recovery was always just around the corner contributed to his unpopularity. By 1932, Americans perceived Hoover as insensitive to the depth of the country’s economic suffering. The nation had come a long way since the depressions of the 1870s and 1890s, when no one except the most radical figures, such as Jacob Coxey, called for direct federal aid to the unemployed. Compared with previous chief executives — and in contrast to his popular image as a “do-nothing” president — Hoover had responded to the national emergency with unprecedented government action. But the nation’s needs were even more unprecedented, and Hoover’s programs failed to meet them (Map 23.1).

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

What economic principles guided President Hoover and Congress in their response to the Great Depression?