America’s History: Printed Page 777

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 706

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 686

Workers and the War Effort

As millions of working-age citizens joined the military, the nation faced a critical labor shortage. Consequently, many women and African Americans joined the industrial workforce, taking jobs unavailable to them before the conflict. Unions, benefitting from the demand for labor, negotiated higher wages and improved conditions for America’s workers. By 1943, with the economy operating at full capacity, the breadlines and double-digit unemployment of the 1930s were a memory.

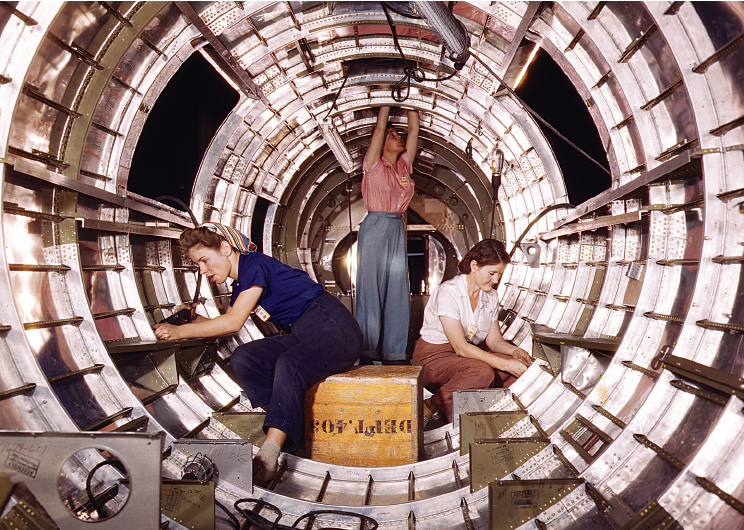

Rosie the Riveter Government officials and corporate recruiters urged women to take jobs in defense industries, creating a new image of working women. “Longing won’t bring him back sooner … GET A WAR JOB!” one poster urged, while artist Norman Rockwell’s famous “Rosie the Riveter” illustration beckoned to women from the cover of the Saturday Evening Post. The government directed its publicity at housewives, but many working women gladly abandoned low-paying “women’s jobs” as domestic servants or secretaries for higher-paying work in the defense industry. Suddenly, the nation’s factories were full of women working as airplane riveters, ship welders, and drill-press operators (American Voices). Women made up 36 percent of the labor force in 1945, compared with 24 percent at the beginning of the war. War work did not free women from traditional expectations and limitations, however. Women often faced sexual harassment on the job and usually received lower wages than men did. In shipyards, women with the most seniority and responsibility earned $6.95 a day, whereas the top men made as much as $22.

Wartime work was thus bittersweet for women, because it combined new opportunities with old constraints. The majority labored in low-wage service jobs. Child care was often unavailable, despite the largest government-sponsored child-care program in history. When the men returned from war, Rosie the Riveter was usually out of a job. Government propaganda now encouraged women back into the home — where, it was implied, their true calling lay in raising families and standing behind the returning soldiers. But many married women refused, or could not afford, to put on aprons and stay home. Women’s participation in the paid labor force rebounded by the late 1940s and continued to rise over the rest of the twentieth century, bringing major changes in family life (discussed in Chapter 26).

Wartime Civil Rights Among African Americans, a new militancy prevailed during the war. Pointing to parallels between anti-Semitism in Germany and racial discrimination in the United States, black leaders waged the Double V campaign: calling for victory over Nazism abroad and racism at home. “This is a war for freedom. Whose freedom?” the renowned black leader W. E. B. Du Bois asked. If it meant “the freedom of Negroes in the Southern United States,” Du Bois answered, “my gun is on my shoulder.”

Even before Pearl Harbor, black labor activism was on the rise. In 1940, only 240 of the nation’s 100,000 aircraft workers were black, and most of them were janitors. African American leaders demanded that the government require defense contractors to hire more black workers. When Washington took no action, A. Philip Randolph, head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the largest black labor union in the country, announced plans for a march on Washington in the summer of 1941.

Roosevelt was not a strong supporter of African American equality, but he wanted to avoid public protest and a disruption of the nation’s war preparations. So the president made a deal: he issued Executive Order 8802, and in June 1941 Randolph canceled the march. The order prohibited “discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin” and established the Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC). Mary McLeod Bethune called the wartime FEPC “a refreshing shower in a thirsty land.” This federal commitment to black employment rights was unprecedented but limited: it did not affect segregation in the armed forces, and the FEPC could not enforce compliance with its orders.

Nevertheless, wartime developments laid the groundwork for the civil rights revolution of the 1960s. The NAACP grew ninefold, to 450,000 members, by 1945. In Chicago, James Farmer helped to found the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in 1942, a group that would become known nationwide in the 1960s for its direct action protests such as sit-ins. The FEPC inspired black organizing against employment discrimination in hundreds of cities and workplaces. Behind this combination of government action and black militancy, the civil rights movement would advance on multiple fronts in the postwar years.

Mexican Americans, too, challenged long-standing practices of discrimination and exclusion. Throughout much of the Southwest, it was still common for signs to read “No Mexicans Allowed,” and Mexican American workers were confined to menial, low-paying jobs. Several organizations, including the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and the Congress of Spanish Speaking Peoples, pressed the government and private employers to end anti-Mexican discrimination. Mexican American workers themselves, often in Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) unions such as the Cannery Workers and Shipyard Workers, also led efforts to enforce the FEPC’s equal employment mandate.

Exploitation persisted, however. To meet wartime labor demands, the U.S. government brought tens of thousands of Mexican contract laborers into the United States under the Bracero Program. Paid little and treated poorly, the braceros (who took their name from the Spanish brazo, “arm”) highlighted the oppressive conditions of farm labor in the United States. After the war, the federal government continued to participate in labor exploitation, bringing hundreds of thousands of Mexicans into the country to perform low-wage agricultural work. Future Mexican American civil rights leaders Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez began to fight this labor system in the 1940s.

Organized Labor During the war, unions solidified their position as the most powerful national voice for American workers and extended gains made during the New Deal. By 1945, almost 15 million workers belonged to a union, up from 9 million in 1939. Representatives of the major unions made a no-strike pledge for the duration of the war, and Roosevelt rewarded them by creating the National War Labor Board (NWLB), composed of representatives of labor, management, and the public. The NWLB established wages, hours, and working conditions and had the authority to seize manufacturing plants that did not comply. The Board’s “maintenance of membership” policy, which encouraged workers in major defense industries to join unions, also helped organized labor grow.

Despite these arrangements, unions endured government constraints and faced a sometimes hostile Congress. Frustrated with limits on wage increases and the no-strike pledge, in 1943 more than half a million United Mine Workers went out on strike, demanding a higher wage increase than that recommended by the NWLB. Congress responded by passing (over Roosevelt’s veto) the Smith-Connally Labor Act of 1943, which allowed the president to prohibit strikes in defense industries and forbade political contributions by unions. Congressional hostility would continue to hamper the union movement in the postwar years. Although organized labor would emerge from World War II more powerful than at any time in U.S. history, its business and corporate opponents, too, would emerge from the war with new strength.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

How does the slogan “A Jim Crow army cannot fight for a free world” connect the war abroad with the civil rights struggle at home?