America’s History: Printed Page 787

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 713

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 693

Japanese Removal

Unlike World War I, which evoked widespread harassment of German Americans, World War II produced relatively little condemnation of European Americans. Federal officials held about 5,000 potentially dangerous German and Italian aliens during the war. Despite the presence of small but vocal groups of Nazi sympathizers and Mussolini supporters, German American and Italian American communities were largely left in peace during the war. The relocation and temporary imprisonment of Japanese immigrants and Japanese American citizens was a glaring exception to this otherwise tolerant policy. Immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the West Coast remained calm. Then, as residents began to fear spies, sabotage, and further attacks, California’s long history of racial animosity toward Asian immigrants surfaced. Local politicians and newspapers whipped up hysteria against Japanese Americans, who numbered only about 112,000, had no political power, and lived primarily in small enclaves in the Pacific coast states.

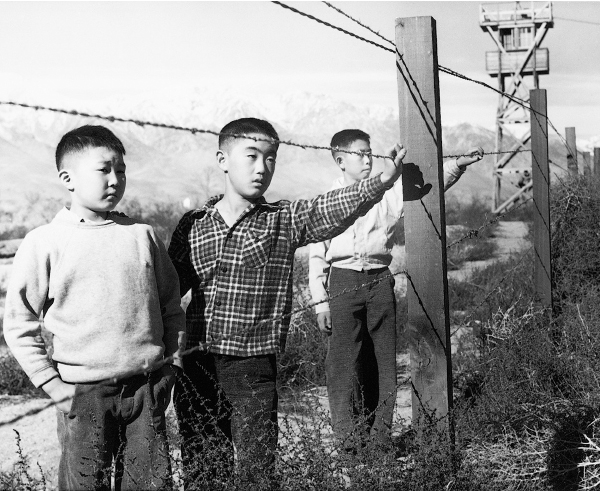

Early in 1942, President Roosevelt responded to anti-Japanese fears by issuing Executive Order 9066, which authorized the War Department to force Japanese Americans from their West Coast homes and hold them in relocation camps for the rest of the war. Although there was no disloyal or seditious activity among the evacuees, few public leaders opposed the plan. “A Jap’s a Jap,” snapped General John DeWitt, the officer charged with defense of the West Coast. “It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen or not.”

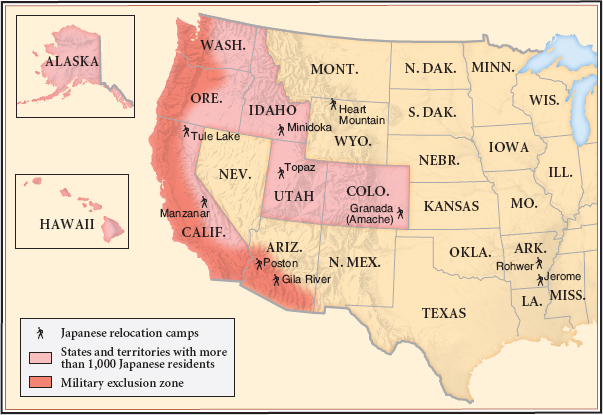

The relocation plan shocked Japanese Americans, more than two-thirds of whom were Nisei; that is, their parents were immigrants, but they were native-born American citizens. Army officials gave families only a few days to dispose of their property. Businesses that had taken a lifetime to build were liquidated overnight. The War Relocation Authority moved the prisoners to hastily built camps in desolate areas in California, Arizona, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, and Arkansas (Map 24.1). Ironically, the Japanese Americans who made up one-third of the population of Hawaii, and presumably posed a greater threat because of their numbers and proximity to Japan, were not imprisoned. They provided much of the unskilled labor in the island territory, and the Hawaiian economy could not have functioned without them.

Cracks soon appeared in the relocation policy. An agricultural labor shortage led the government to furlough seasonal farmworkers from the camps as early as 1942. About 4,300 students were allowed to attend colleges outside the West Coast military zone. Other internees were permitted to join the armed services. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a unit composed almost entirely of Nisei volunteers, served with distinction in Europe.

Gordon Hirabayashi was among the Nisei who actively resisted incarceration. A student at the University of Washington, Hirabayashi was a religious pacifist who had registered with his draft board as a conscientious objector. He refused to report for evacuation and turned himself in to the FBI. “I wanted to uphold the principles of the Constitution,” Hirabayashi later stated, “and the curfew and evacuation orders which singled out a group on the basis of ethnicity violated them.” Tried and convicted in 1942, he appealed his case to the Supreme Court in Hirabayashi v. United States (1943). In that case and in Korematsu v. United States (1944), the Court allowed the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast on the basis of “military necessity” but avoided ruling on the constitutionality of the incarceration program. The Court’s decision underscored the fragility of civil liberties in wartime. Congress issued a public apology in 1988 and awarded $20,000 to each of the eighty thousand surviving Japanese Americans who had once been internees.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

Why were Japanese Americans treated differently than German and Italian Americans during the war?