America’s History: Printed Page 788

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 715

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 695

The War in Europe

Throughout 1942, the Allies suffered one defeat after another. German armies pushed deep into Soviet territory, advancing through the wheat farms of the Ukraine and the rich oil region of the Caucasus. Simultaneously, German forces began an offensive in North Africa aimed at seizing the Suez Canal. In the Atlantic, U-boats devastated American convoys carrying oil and other vital supplies to Britain and the Soviet Union.

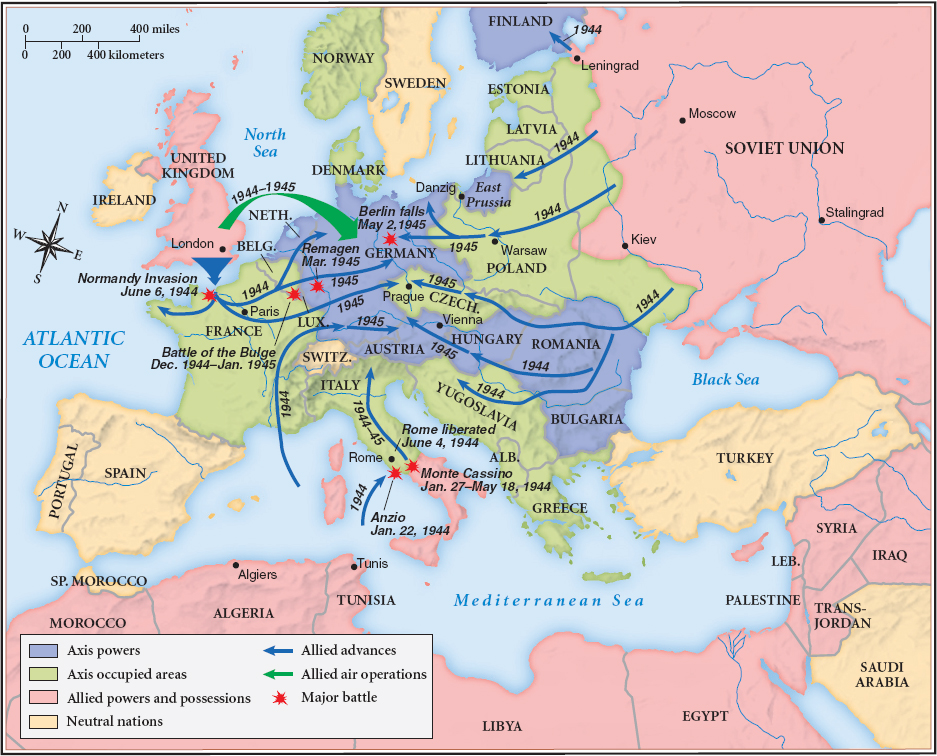

Over the winter of 1942–1943, however, the tide began to turn in favor of the Allies. In the epic Battle of Stalingrad, Soviet forces not only halted the German advance but also allowed the Russian army to push westward (Map 24.2). By early 1944, Stalin’s troops had driven the German army out of the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, as Churchill’s temporary substitute for a second front in France, the Allies launched a major counteroffensive in North Africa. Between November 1942 and May 1943, Allied troops under the leadership of General Dwight D. Eisenhower and General George S. Patton defeated the German Afrika Korps, led by General Erwin Rommel.

From Africa, the Allied command followed Churchill’s strategy of attacking the Axis through its “soft underbelly”: Sicily and the Italian peninsula. Faced with an Allied invasion, the Italian king ousted Mussolini’s fascist regime in July 1943. But German troops, who far outmatched the Allies in skill and organization, took control of Italy and strenuously resisted the Allied invasion. American and British divisions took Rome only in June 1944 and were still fighting German forces in northern Italy when the European war ended in May 1945 (Map 24.3). Churchill’s southern strategy proved a time-consuming and costly mistake.

D-Day The long-promised invasion of France came on D-Day, June 6, 1944. That morning, the largest armada ever assembled moved across the English Channel under the command of General Eisenhower. When American, British, and Canadian soldiers hit the beaches of Normandy, they suffered terrible casualties but secured a beachhead. Over the next few days, more than 1.5 million soldiers and thousands of tons of military supplies and equipment flowed into France. Much to the Allies’ advantage, they never faced more than one-third of Hitler’s Wehrmacht (armed forces), because the Soviet Union continued to hold down the Germans on the eastern front. In August, Allied troops liberated Paris; by September, they had driven the Germans out of most of France and Belgium. Meanwhile, long-range Allied bombers attacked German cities such as Hamburg and Dresden as well as military and industrial targets. The air campaign killed some 305,000 civilians and soldiers and injured another 780,000 — a grisly reminder of the war’s human brutality.

The Germans were not yet ready to give up, however. In December 1944, they mounted a final offensive in Belgium, the so-called Battle of the Bulge, before being pushed back across the Rhine River into Germany. American and British troops drove toward Berlin from the west, while Soviet troops advanced east through Poland. On April 30, 1945, as Russian troops massed outside Berlin, Hitler committed suicide; on May 7, Germany formally surrendered.

The Holocaust When Allied troops advanced into Poland and Germany in the spring of 1945, they came face-to-face with Hitler’s “final solution” for the Jewish population of Germany and the German-occupied countries: the extermination camps in which 6 million Jews had been put to death, along with another 6 million Poles, Slavs, Gypsies, homosexuals, and other “undesirables.” Photographs of the Nazi death camps at Buchenwald, Dachau, and Auschwitz showed bodies stacked like cordwood and survivors so emaciated that they were barely alive. Published in Life and other mass-circulation magazines, the photographs of the Holocaust horrified the American public and the world.

The Nazi persecution of German Jews in the 1930s was widely known in the United States. But when Jews had begun to flee Europe, the United States refused to relax its strict immigration laws to take them in. In 1939, when the SS St. Louis, a German ocean liner carrying nearly a thousand Jewish refugees, sought permission from President Roosevelt to dock at an American port, FDR had refused. Its passengers’ futures uncertain, the St. Louis was forced to return to Europe, where many would later be deported to Auschwitz and other extermination camps. American officials, along with those of most other nations, continued this exclusionist policy during World War II as the Nazi regime extended its control over millions of Eastern European Jews.

Various factors inhibited American action, but the most important was widespread anti-Semitism: in the State Department, Christian churches, and the public at large. The legacy of the immigration restriction legislation of the 1920s and the isolationist attitudes of the 1930s also discouraged policymakers from assuming responsibility for the fate of the refugees. Taking a narrow view of the national interest, the State Department allowed only 21,000 Jewish refugees to enter the United States during the war. But the War Refugee Board, which President Roosevelt established in 1944 at the behest of Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, helped move 200,000 European Jews to safe havens in other countries.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

How did the Allies disagree over military strategy?