America’s History: Printed Page 793

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 719

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 700

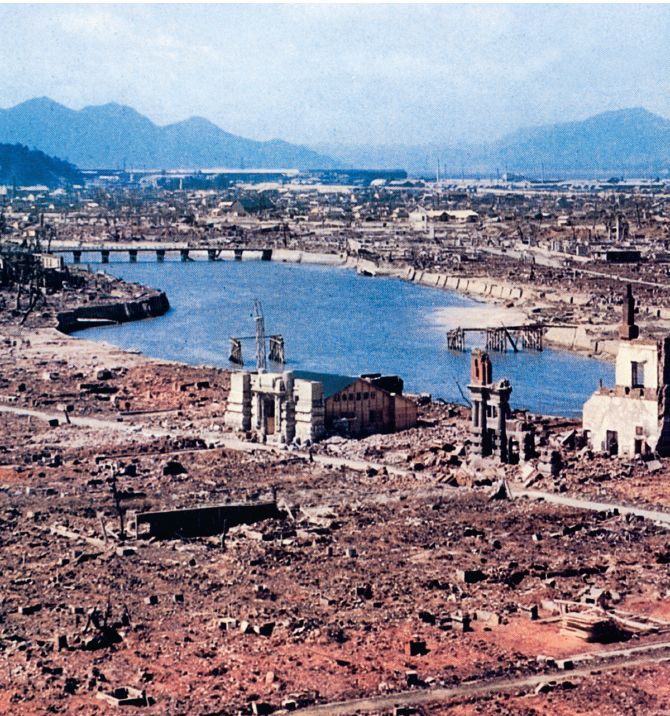

The Atomic Bomb and the End of the War

When Harry Truman assumed the presidency, he learned for the first time about the top-secret Manhattan Project, which was on the verge of testing a new weapon: the atomic bomb. Working at the University of Chicago in December 1942, Enrico Fermi and Leo Szilard, refugees from fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, produced the first controlled atomic chain reaction using highly processed uranium. With the aid of German-born refugee Albert Einstein, the greatest theorist of modern physics and a scholar at Princeton, they persuaded Franklin Roosevelt to develop an atomic weapon, warning that German scientists were also working on such nuclear reactions.

The Manhattan Project cost $2 billion, employed 120,000 people, and involved the construction of thirty-seven installations in nineteen states — with all of its activity hidden from Congress, the American people, and even Vice President Truman. Directed by General Leslie Graves and scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer, the nation’s top physicists assembled the first bomb in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and successfully tested it on July 16, 1945. Overwhelmed by its frightening power, as he witnessed the first mushroom cloud, Oppenheimer recalled the words from the Bhagavad Gita, one of the great texts of Hindu scripture: “I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds.”

Three weeks later, President Truman ordered the dropping of atomic bombs on two Japanese cities: Hiroshima on August 6 and Nagasaki on August 9. Truman’s rationale for this order — and the implications of his decision — have long been the subject of scholarly and popular debate. The principal reason was straightforward: Truman and his American advisors, including Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall, believed that Japan’s military leaders would never surrender unless their country faced national ruin. Moreover, at the Potsdam Conference on the outskirts of Berlin in July 1945, the Allies had agreed that only the “unconditional surrender” of Japan was acceptable — the same terms under which Germany and Italy had been defeated. To win such a surrender, an invasion of Japan itself seemed necessary. Stimson and Marshall told Truman that such an invasion would produce between half a million and a million Allied casualties.

Before giving the order to drop the atomic bomb, Truman considered other options. His military advisors rejected the most obvious alternative: a nonlethal demonstration of the bomb’s awesome power, perhaps on a remote Pacific island. If the demonstration failed — not out of the question, as the bomb had been tested only once — it would embolden Japan further. A detailed advance warning designed to scare Japan into surrender was also rejected. Given Japan’s tenacious fighting in the Pacific, the Americans believed that only massive devastation or a successful invasion would lead Japan’s military leadership to surrender. After all, the deaths of more than 100,000 Japanese civilians in the U.S. firebombing of Tokyo and other cities in the spring of 1945 had brought Japan no closer to surrender.

In any event, the atomic bombs achieved the immediate goal. The deaths of 100,000 people at Hiroshima and 60,000 at Nagasaki prompted the Japanese government to surrender unconditionally on August 10 and to sign a formal agreement on September 2, 1945. Fascism had been defeated, thanks to a fragile alliance between the capitalist nations of the West and the communist government of the Soviet Union. The coming of peace would strain and then destroy the victorious coalition. Even as the global war came to an end, the early signs of the coming Cold War were apparent, as were the stirrings of independence in the European colonies.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

What factors influenced Truman’s decision to use atomic weapons against Japan?