America’s History: Printed Page 769

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 696

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 679

War Approaches

As Hitler pushed his initiatives in Europe, which was mired in economic depression as deeply as the United States, the Roosevelt administration faced widespread isolationist sentiment at home. In part, this desire to avoid European entanglements reflected disillusion with American participation in World War I. In 1934, Gerald P. Nye, a progressive Republican senator from North Dakota, launched an investigation into the profits of munitions makers during that war. Nye’s committee alleged that arms manufacturers (popularly labeled “merchants of death”) had maneuvered President Wilson into World War I.

Although Nye’s committee failed to prove its charge against weapon makers, its factual findings prompted an isolationist-minded Congress to pass a series of acts to prevent the nation from being drawn into another overseas war. The Neutrality Act of 1935 imposed an embargo on selling arms to warring countries and declared that Americans traveling on the ships of belligerent nations did so at their own risk. In 1936, Congress banned loans to belligerents, and in 1937 it imposed a “cash-and-carry” requirement: if a warring country wanted to purchase nonmilitary goods from the United States, it had to pay cash and carry them in its own ships, keeping the United States out of potentially dangerous naval warfare.

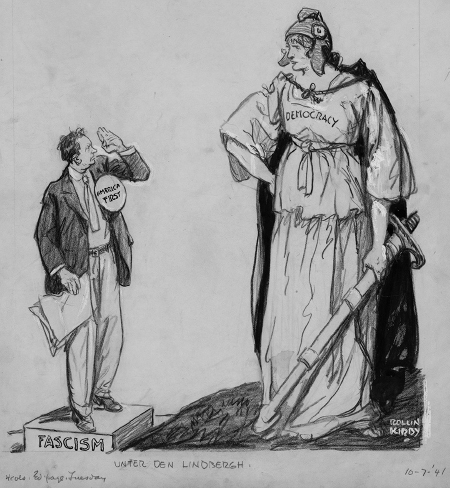

Americans for the most part had little enthusiasm for war, and a wide variety of groups and individuals espoused isolationism. Many isolationists looked to Republican Ohio senator Robert Taft, who distrusted both Roosevelt and European nations with equal conviction, or to the aviator hero Charles A. Lindbergh, who delivered impassioned speeches against intervention in Europe. Some isolationists, such as the conservative National Legion of Mothers of America, combined anticommunism, Christian morality, and even anti-Semitism. Isolationists were primarily conservatives, but a contingent of progressives (or liberals) opposed America’s involvement in the war on pacifist or moral grounds. Whatever their philosophies, ardent isolationists forced Roosevelt to approach the brewing war cautiously.

The Popular Front Other Americans responded to the rise of European fascism by advocating U.S. intervention. Some of the most prominent Americans pushing for greater involvement in Europe, even if it meant war, were affiliated with the Popular Front. Fearful of German and Japanese aggression, the Soviet Union instructed Communists in Western Europe and the United States to join with liberals in a broad coalition opposing fascism. This Popular Front supported various international causes — backing the Loyalists in their fight against fascist leader Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), for example, even as the United States, France, and Britain remained neutral.

In the United States, the Popular Front drew from a wide range of social groups. The American Communist Party, which had increased its membership to 100,000 as the depression revealed flaws in the capitalist system, led the way. African American civil rights activists, trade unionists, left-wing writers and intellectuals, and even a few New Deal administrators also joined the coalition. In time, however, many supporters in the United States grew uneasy with the Popular Front because of the rigidity of Communists and the brutal political repression in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin. Nevertheless, Popular Front activists were among a small but vocal group of Americans encouraging Roosevelt to take a stronger stand against European fascism.

The Failure of Appeasement Encouraged by the weak worldwide response to the invasions of China, Ethiopia, and the Rhineland, and emboldened by British and French neutrality during the Spanish Civil War, Hitler grew more aggressive in 1938. He sent troops to annex German-speaking Austria while making clear his intention to seize part of Czechoslovakia. Because Czechoslovakia had an alliance with France, war seemed imminent. But at the Munich Conference in September 1938, Britain and France capitulated, agreeing to let Germany annex the Sudetenland — a German-speaking border area of Czechoslovakia — in return for Hitler’s pledge to seek no more territory. The agreement, declared British prime minister Neville Chamberlain, guaranteed “peace for our time.” Hitler drew a different conclusion, telling his generals: “Our enemies are small fry. I saw them in Munich.”

Within six months, Hitler’s forces had overrun the rest of Czechoslovakia and were threatening to march into Poland. Realizing that their policy of appeasement — capitulating to Hitler’s demands — had been disastrous, Britain and France warned Hitler that further aggression meant war. Then, in August 1939, Hitler and Stalin shocked the world by signing a mutual nonaggression pact. For Hitler, this pact was crucial, as it meant that Germany would not have to wage a two-front war against Britain and France in the west and the Soviet Union in the east. On September 1, 1939, Hitler launched a blitzkrieg against Poland. Two days later, Britain and France declared war on Germany. World War II had officially begun.

Two days after the European war started, the United States declared its neutrality. But President Roosevelt made no secret of his sympathies. When war broke out in 1914, Woodrow Wilson had told Americans to be neutral “in thought as well as in action.” FDR, by contrast, now said: “This nation will remain a neutral nation, but I cannot ask that every American remain neutral in thought as well.” The overwhelming majority of Americans — some 84 percent, according to a poll in 1939 — supported Britain and France rather than Germany, but most wanted America to avoid another European war.

At first, the need for U.S. intervention seemed remote. After Germany conquered Poland in September 1939, calm settled over Europe. Then, on April 9, 1940, German forces invaded Denmark and Norway. In May, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg fell to the swift German army. The final shock came in mid-June, when France too surrendered. Britain now stood alone against Hitler’s plans for domination of Europe.

Isolationism and Internationalism What Time magazine would later call America’s “thousand-step road to war” had already begun. After a bitter battle in Congress in 1939, Roosevelt won a change in the neutrality laws to allow the Allies to buy arms as well as nonmilitary goods on a cash-and-carry basis. Interventionists, led by journalist William Allen White and his Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, became increasingly vocal in 1940 as war escalated in Europe. (Interventionists were also known as “internationalists,” since they believed in engaging with, rather than withdrawing from, international developments.) In response, isolationists formed the America First Committee (AFC), with well-respected figures such as Lindbergh and Senator Nye urging the nation to stay out of the war. The AFC held rallies across the United States, and its posters, brochures, and broadsides warning against American involvement in Europe suffused many parts of the country, especially the Midwest.

Because of the America Firsters’ efforts, Roosevelt proceeded cautiously in 1940 as he moved the United States closer to involvement. The president did not want war, but he believed that most Americans “greatly underestimate the serious implications to our own future,” as he confided to White. In May, Roosevelt created the National Defense Advisory Commission and brought two prominent Republicans, Henry Stimson and Frank Knox, into his cabinet as secretaries of war and the navy, respectively. During the summer, the president traded fifty World War I destroyers to Great Britain in exchange for the right to build military bases on British possessions in the Atlantic, circumventing neutrality laws by using an executive order to complete the deal. In October 1940, a bipartisan vote in Congress approved a large increase in defense spending and instituted the first peacetime draft in American history. “We must be the great arsenal of democracy,” FDR declared.

As the war in Europe and the Pacific expanded, the United States was preparing for the 1940 presidential election. The crisis had convinced Roosevelt to seek an unprecedented third term. The Republicans nominated Wendell Willkie of Indiana, a former Democrat who supported many New Deal policies. The two parties’ platforms differed only slightly. Both pledged aid to the Allies, and both candidates promised not to “send an American boy into the shambles of a European war,” as Willkie put it. Willkie’s spirited campaign resulted in a closer election than that of 1932 or 1936; nonetheless, Roosevelt won 55 percent of the popular vote.

Having been reelected, Roosevelt now undertook to persuade Congress to increase aid to Britain, whose survival he viewed as key to American security. In January 1941, he delivered one of the most important speeches of his career. Defining “four essential human freedoms” — freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from want, and freedom from fear — Roosevelt cast the war as a noble defense of democratic societies. He then linked the fate of democracy in Western Europe with the new welfare state at home. Sounding a decidedly New Deal note, Roosevelt pledged to end “special privileges for the few” and to preserve “civil liberties for all.” Like President Wilson’s speech championing national self-determination at the close of World War I, Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” speech outlined a liberal international order with appeal well beyond its intended European and American audiences.

|

To see a longer excerpt of the “Four Freedoms” speech, along with other primary sources from this period, see Sources for America’s History. |

Two months later, in March 1941, with Britain no longer able to pay cash for arms, Roosevelt persuaded Congress to pass the Lend-Lease Act. The legislation authorized the president to “lease, lend, or otherwise dispose of” arms and equipment to Britain or any other country whose defense was considered vital to the security of the United States. When Hitler abandoned his nonaggression pact with Stalin and invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the United States extended lend-lease to the Soviets. The implementation of lend-lease marked the unofficial entrance of the United States into the European war.

Roosevelt underlined his support for the Allied cause by meeting in August 1941 with British prime minister Winston Churchill (who had succeeded Chamberlain in 1940). Their joint press release, which became known as the Atlantic Charter, provided the ideological foundation of the Western cause. Drawing from Wilson’s Fourteen Points and Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms, the charter called for economic cooperation, national self-determination, and guarantees of political stability after the war to ensure “that all men in all the lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want.” It would become the basis for a new American-led transatlantic alliance after the war’s conclusion. Its promise of national self-determination, however, set up potential conflict in Asia and Africa, where European powers would be reluctant to abandon their imperial holdings.

In the fall of 1941, the reality of U.S. involvement in the war drew closer. By September, Nazi U-boats and the American navy were exchanging fire in the Atlantic. With isolationists still a potent force, Roosevelt hesitated to declare war and insisted that the United States would defend itself only against a direct attack. But behind the scenes, the president openly discussed American involvement with close advisors and considered war inevitable.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

How did Roosevelt use the Four Freedoms speech and the Atlantic Charter to define the war for Americans?