America’s History: Printed Page 804

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 730

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 710

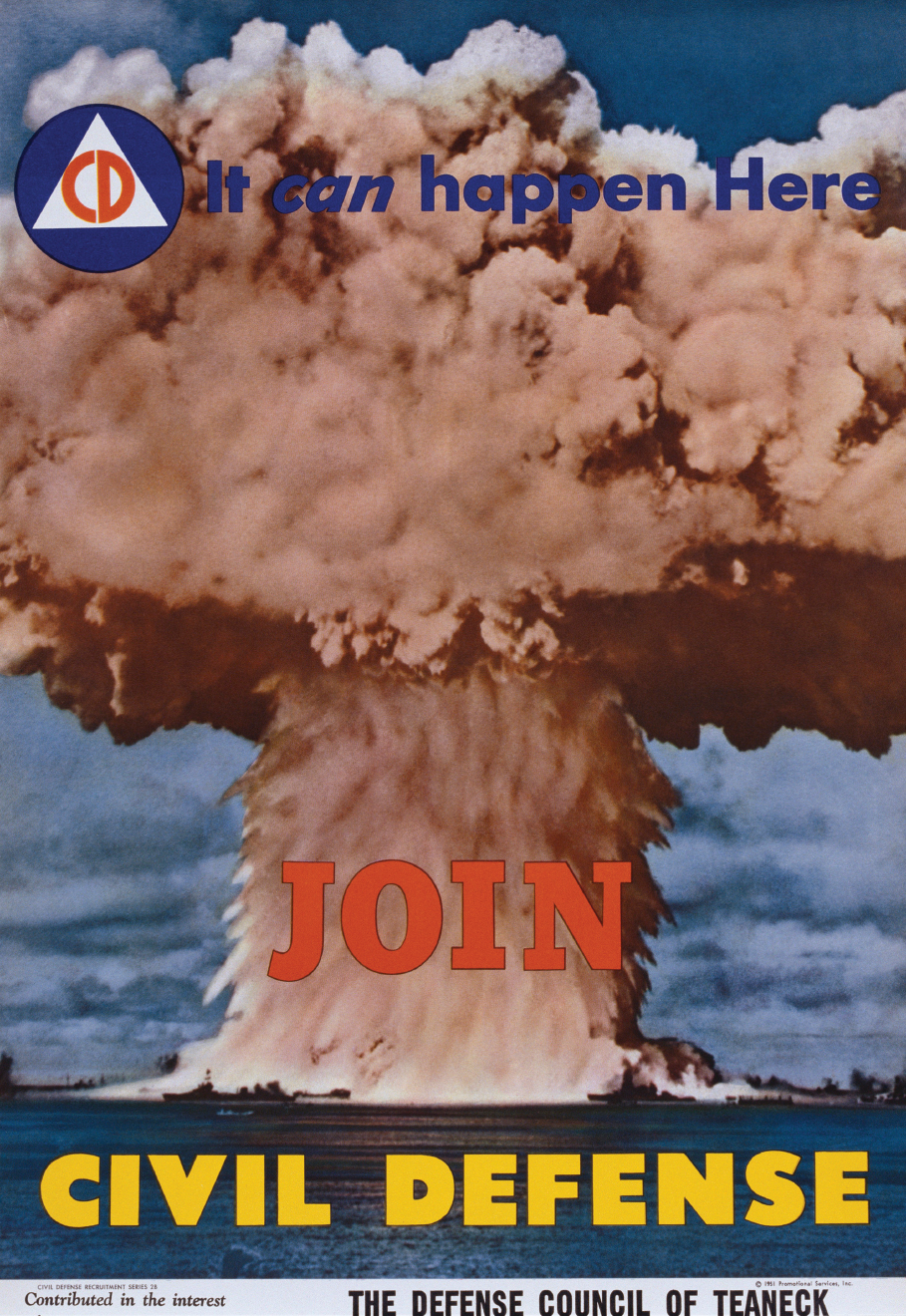

Cold War America

1945–1963

25

CHAPTER

IDENTIFY THE BIG IDEA

In the first two decades of the Cold War, how did competition on the international stage and a climate of fear at home affect politics, society, and culture in the United States?

In the autumn of 1950, a little-known California congressman running for the Senate named Richard M. Nixon stood before reporters in Los Angeles. His opponent, Helen Gahagan Douglas, was a Hollywood actress and a New Deal Democrat. Nixon told the gathered reporters that Douglas had cast “Communist-leaning” votes and that she was “pink right down to her underwear.” Gahagan’s voting record was not much different from Nixon’s. But tarring her with communism made her seem un-American, and Nixon defeated the “pink lady” with nearly 60 percent of the vote.

A few months earlier, U.S. tanks, planes, and artillery supplies had arrived in French Indochina. A French colony since the nineteenth century, Indochina (present-day Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) was home to an independence movement led by Ho Chi Minh and supported by the Soviet Union and China. In the summer of 1950, President Harry S. Truman authorized $15 million worth of military supplies to aid France, which was fighting Ho’s army to keep possession of its Indochinese empire. “Neither national independence nor democratic evolution exists in any area dominated by Soviet imperialism,” Secretary of State Dean Acheson warned ominously as he announced U.S. support for French imperialism.

Connecting these coincidental historical moments, one domestic and the other international, was a decades-old force in American life that gained renewed strength after World War II: anticommunism. The events in Los Angeles and Vietnam, however different on the surface, were part of the global geopolitical struggle between the democratic United States and the communist, authoritarian Soviet Union known as the Cold War. Beginning in Europe as World War II ended and extending to Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa by the mid-1950s, the Cold War reshaped international relations and dominated global politics for more than forty years.

In the United States, the Cold War fostered suspicion of “subversives” in government, education, and the media. The arms race that developed between the two superpowers prompted Congress to boost military expenditures. The resulting military-industrial complex enhanced the power of the corporations that built planes, munitions, and electronic devices. In politics, the Cold War stifled liberal initiatives as the New Deal coalition tried to advance its domestic agenda in the shadow of anticommunism. In these ways, the line between the international and the domestic blurred — and that blurred line was another enduring legacy of the Cold War.