America’s History: Printed Page 818

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 743

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 723

Truman and the End of Reform

Truman and the Democratic Party of the late 1940s and early 1950s forged what historians call Cold War liberalism. They preserved the core programs of the New Deal welfare state, developed the containment policy to oppose Soviet influence throughout the world, and fought so-called subversives at home. But there would be no second act for the New Deal. The Democrats adopted this combination of moderate liberal policies and anticommunism — Cold War liberalism — partly by choice and partly out of necessity. A few high-level espionage scandals and the Communist victories in Eastern Europe and China reenergized the Republican Party, which forced Truman and the Democrats to retreat to what historian Arthur Schlesinger called the “vital center” of American politics. However, Americans on both the progressive left and the conservative right remained dissatisfied with this development. Cold War liberalism was a practical centrist policy for a turbulent era. But it would not last.

Organized labor remained a key force in the Democratic Party and played a central role in championing Cold War liberalism. Stronger than ever, union membership swelled to more than 14 million by 1945. Determined to make up for their wartime sacrifices, unionized workers made aggressive demands and mounted major strikes in the automobile, steel, and coal industries after the war. Republicans responded. They gained control of the House in a sweeping repudiation of Democrats in 1946 and promptly passed — over Truman’s veto — the Taft-Hartley Act (1947), an overhaul of the 1935 National Labor Relations Act.

Taft-Hartley crafted changes in procedures and language that, over time, weakened the right of workers to organize and engage in collective bargaining. Unions especially disliked Section 14b, which allowed states to pass “right-to-work” laws prohibiting the union shop. Additionally, the law forced unions to purge communists, who had been among the most successful labor organizers in the 1930s, from their ranks. Taft-Hartley effectively “contained” the labor movement. Trade unions would continue to support the Democratic Party, but the labor movement would not move into the largely non-union South and would not extend into the many American industries that remained unorganized.

The 1948 Election Democrats would have dumped Truman in 1948 had they found a better candidate. But the party fell into disarray. The left wing split off and formed the Progressive Party, nominating Henry A. Wallace, an avid New Dealer whom Truman had fired as secretary of commerce in 1946 because Wallace opposed America’s actions in the Cold War. A right-wing challenge came from the South. When northern liberals such as Mayor Hubert H. Humphrey of Minneapolis pushed through a strong civil rights platform at the Democratic convention, the southern delegations bolted and, calling themselves Dixiecrats, nominated for president South Carolina governor Strom Thurmond, an ardent supporter of racial segregation. The Republicans meanwhile renominated Thomas E. Dewey, the politically moderate governor of New York who had run a strong campaign against FDR in 1944.

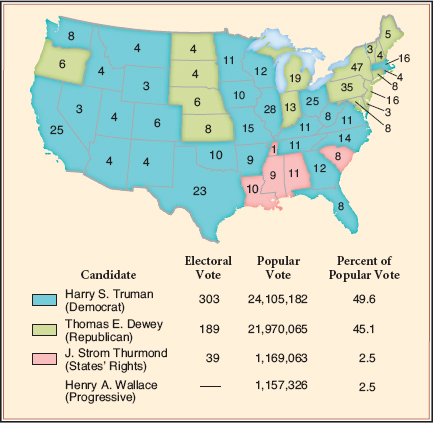

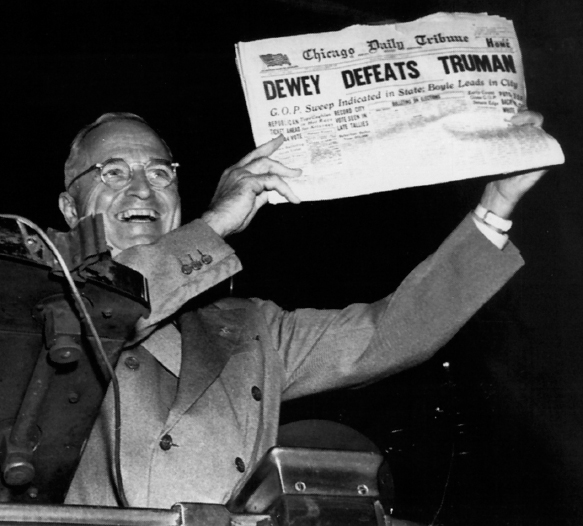

Truman surprised everyone. He launched a strenuous cross-country speaking tour and hammered away at the Republicans for opposing progressive legislation and, in general, for running a “do-nothing” Congress. By combining these issues with attacks on the Soviet menace abroad, Truman began to salvage his troubled campaign. At his rallies, enthusiastic listeners shouted, “Give ’em hell, Harry!” Truman won, receiving 49.6 percent of the vote to Dewey’s 45.1 percent (Map 25.4).

This remarkable election foreshadowed coming political turmoil. Truman occupied the center of FDR’s sprawling New Deal coalition. On his left were progressives, civil rights advocates, and anti-Cold War peace activists. On his right were segregationist southerners, who opposed civil rights and were allied with Republicans on many economic and foreign policy issues. In 1948, Truman performed a delicate balancing act, largely retaining the support of Jewish and Catholic voters in the big cities, black voters in the North, and organized labor voters across the country. But Thurmond’s strong showing — he carried four states in the Deep South — demonstrated the fragile nature of the Democratic coalition and prefigured the revolt of the party’s southern wing in the 1960s. As he tried to manage contending forces in his own party, Truman faced mounting pressure from Republicans to denounce radicals at home and to take a tough stand against the Soviet Union.

The Fair Deal Despite having to perform a balancing act, Truman and progressive Democrats forged ahead. In 1949, reaching ambitiously to extend the New Deal, Truman proposed the Fair Deal: national health insurance, aid to education, a housing program, expansion of Social Security, a higher minimum wage, and a new agricultural program. In its attention to civil rights, the Fair Deal also reflected the growing role of African Americans in the Democratic Party. Congress, however, remained a huge stumbling block, and the Fair Deal fared poorly. The same conservative coalition that had blocked Roosevelt’s initiatives in his second term continued the fight against Truman’s. Cold War pressure shaped political arguments about domestic social programs, while the nation’s growing paranoia over internal subversion weakened support for bold extensions of the welfare state. Truman’s proposal for national health insurance, for instance, was a popular idea, with strong backing from organized labor. But it was denounced as “socialized medicine” by the American Medical Association and the insurance industry. In the end, the Fair Deal’s only significant breakthrough, other than improvements to the minimum wage and Social Security, was the National Housing Act of 1949, which authorized the construction of 810,000 low-income units.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

How was the Democratic Party divided in 1948, and what were its primary constituencies?