America’s History: Printed Page 829

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 755

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 733

John F. Kennedy and the Cold War

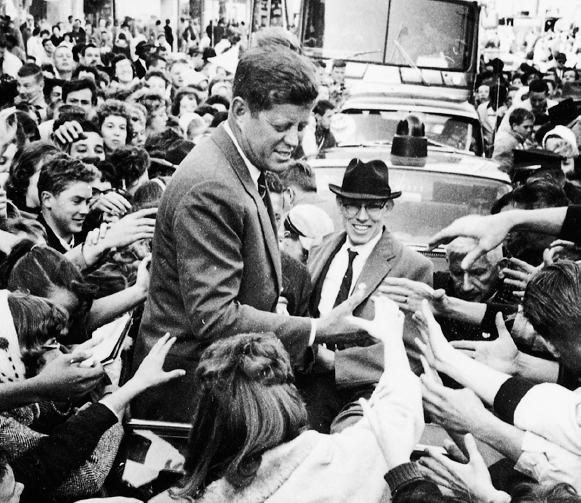

Charisma, style, and personality — these, more than platforms and issues, defined a new brand of politics in the early 1960s. This was John F. Kennedy’s natural environment. Kennedy, a Harvard alumnus, World War II hero, and senator from Massachusetts, had inherited his love of politics from his grandfathers — colorful, and often ruthless, Irish Catholic politicians in Boston. Ambitious and deeply aware of style, the forty-three-year-old Kennedy made use of his many advantages to become, as novelist Norman Mailer put it, “our leading man.” His one disadvantage — that he was Catholic in a country that had never elected a Catholic president — he masterfully neutralized. And thanks to both media advisors and his youthful attractiveness, Kennedy projected a superb television image.

At heart, however, Kennedy was a Cold Warrior who had come of age in the shadow of Munich, Yalta, and McCarthyism. He projected an air of idealism, but his years in the Senate (1953–1960) had proved him to be a conventional Cold War politician. Once elected president, Kennedy would shape the nation’s foreign policy by drawing both on his ingenuity and on old-style Cold War power politics.

The Election of 1960 and the New Frontier Kennedy’s Republican opponent in the 1960 presidential election, Eisenhower’s vice president, Richard Nixon, was a seasoned politician and Cold Warrior himself. The great innovation of the 1960 campaign was a series of four nationally televised debates. Nixon, less photogenic than Kennedy, looked sallow and unshaven under the intense studio lights. Voters who heard the first debate on the radio concluded that Nixon had won, but those who viewed it on television favored Kennedy. Despite the edge Kennedy enjoyed in the debates, he won only the narrowest of electoral victories, receiving 49.7 percent of the popular vote to Nixon’s 49.5 percent. Kennedy attracted Catholics, African Americans, and the labor vote; his vice-presidential running mate, Texas senator Lyndon Baines Johnson, helped bring in southern Democrats. Yet only 120,000 votes separated the two candidates, and a shift of a few thousand votes in key states would have reversed the outcome.

Kennedy brought to Washington a cadre of young, ambitious newcomers, including Robert McNamara, a renowned systems analyst and former head of Ford Motor Company, as secretary of defense. A host of trusted advisors and academics flocked to Washington to join the New Frontier — Kennedy’s term for the challenges the country faced. Included on the team as attorney general was Kennedy’s younger brother Robert, who had made a name as a hard-hitting investigator of organized crime. Relying on an old American trope, Kennedy’s New Frontier suggested masculine toughness and adventurism and encouraged Americans to again think of themselves as exploring uncharted terrain. That terrain proved treacherous, however, as the new administration immediately faced a crisis.

Crises in Cuba and Berlin In January 1961, the Soviet Union announced that it intended to support “wars of national liberation” wherever in the world they occurred. Kennedy took Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev’s words as a challenge, especially as they applied to Cuba, where in 1959 Fidel Castro had overthrown the right-wing dictator Fulgencio Batista and declared a revolution. Determined to keep Cuba out of the Soviet orbit, Kennedy followed through on Eisenhower administration plans to dispatch Cuban exiles to foment an anti-Castro uprising. The invaders, trained by the Central Intelligence Agency, were ill-prepared for their task. On landing at Cuba’s Bay of Pigs on April 17, 1961, the force of 1,400 was crushed by Castro’s troops. Kennedy prudently rejected CIA pleas for a U.S. air strike. Accepting defeat, Kennedy went before the American people and took full responsibility for the fiasco (Map 25.6).

Already strained by the Bay of Pigs incident, U.S.-Soviet relations deteriorated further in June 1961 when Khrushchev stopped movement between Communist-controlled East Berlin and the city’s Western sector. Kennedy responded by dispatching 40,000 more troops to Europe. In mid-August, to stop the exodus of East Germans, the Communist regime began constructing the Berlin Wall, policed by border guards under shoot-to-kill orders. Until the 12-foot-high concrete barrier came down in 1989, it served as the supreme symbol of the Cold War.

A perilous Cold War confrontation came next, in October 1962. In a somber televised address on October 22, Kennedy revealed that U.S. reconnaissance planes had spotted Soviet-built bases for intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Cuba. Some of those weapons had already been installed, and more were on the way. Kennedy announced that the United States would impose a “quarantine on all offensive military equipment” on its way to Cuba. As the world held its breath waiting to see if the conflict would escalate into war, on October 25, ships carrying Soviet missiles turned back. After a week of tense negotiations, both sides made concessions: Kennedy pledged not to invade Cuba, and Khrushchev promised to dismantle the missile bases. Kennedy also secretly ordered U.S. missiles to be removed from Turkey, at Khrushchev’s insistence. The risk of nuclear war, greater during the Cuban missile crisis than at any other time in the Cold War, prompted a slight thaw in U.S.-Soviet relations. As National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy put it, both sides were chastened by “having come so close to the edge.”

Kennedy and the World Kennedy also launched a series of bold nonmilitary initiatives. One was the Peace Corps, which embodied a call to public service put forth in his inaugural address (“Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country”). Thousands of men and women agreed to devote two or more years as volunteers for projects such as teaching English to Filipino schoolchildren or helping African villagers obtain clean water. Exhibiting the idealism of the early 1960s, the Peace Corps was also a low-cost Cold War weapon intended to show the developing world that there was an alternative to communism. Kennedy championed space exploration, as well. In a 1962 speech, he proposed that the nation commit itself to landing a man on the moon within the decade. The Soviets had already beaten the United States into space with the 1957 Sputnik satellite and the 1961 flight of cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin. Capitalizing on America’s fascination with space, Kennedy persuaded Congress to increase funding for the government’s space agency, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), enabling the United States to pull ahead of the Soviet Union. Kennedy’s ambition was realized when U.S. astronauts arrived on the moon in 1969.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

How was Kennedy’s approach to the Cold War similar to and different from Eisenhower’s and Truman’s?