America’s History: Printed Page 808

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 734

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 715

The Containment Strategy

In the late 1940s, American officials developed a clear strategy toward the Soviet Union that would become known as containment. Convinced that the USSR was methodically expanding its reach, the United States would counter by limiting Stalin’s influence to Eastern Europe while reconstituting democratic governments in Western Europe. In 1946–1947, three specific issues worried Truman and his advisors. First, the Soviet Union was pressing Iran for access to oil and Turkey for access to the Mediterranean. Second, a civil war was roiling in Greece, between monarchists backed by England and insurgents supported by the Greek and Yugoslavian Communist parties. Third, as European nations suffered through terrible privation in 1946 and 1947, Communist parties gained strength, particularly in France and Italy. All three developments, as seen from the United States, threatened to expand the influence of the Soviet Union outside of Eastern Europe.

Toward an Uneasy Peace In this anxious context, the strategy of containment emerged in a series of incremental steps between 1946 and 1949. In February 1946, American diplomat George F. Kennan first proposed the idea in an 8,000-word cable — a confidential message to the U.S. State Department — from his post at the U.S. embassy in Moscow. Kennan argued that the Soviet Union was an “Oriental despotism” and that communism was merely the “fig leaf” justifying Soviet aggression. A year after writing this cable (dubbed the Long Telegram), he published an influential Foreign Affairs article, arguing that the West’s only recourse was to meet the Soviets “with unalterable counter-force at every point where they show signs of encroaching upon the interests of a peaceful and stable world.” Kennan called for “long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies.” Containment, the key word, came to define America’s evolving strategic stance toward the Soviet Union.

|

To see a longer excerpt of the Long Telegram, along with other primary sources from this period, see Sources for America’s History. |

Kennan believed that the Soviet system was inherently unstable and would eventually collapse. Containment would work, he reasoned, as long as the United States and its allies opposed Soviet expansion in all parts of the world. Kennan’s attentive readers included Stalin himself, who quickly obtained a copy of the classified Long Telegram. The Soviet leader saw the United States as an imperialist aggressor determined to replace Great Britain as the world’s dominant capitalist power. Just as Kennan thought that the Soviet system was despotic and unsustainable, Stalin believed that the West suffered from its own fatal weaknesses. Neither side completely understood or trusted the other, and each projected its worst fears onto the other.

In fact, Britain’s influence in the world was declining. Exhausted by the war, facing enormous budget deficits and a collapsing economy at home, and confronted with a determined independence movement in India led by Mohandas Gandhi and growing nationalist movements throughout its empire, Britain was waning as a global power. “The reins of world leadership are fast slipping from Britain’s competent but now very weak hands,” read a U.S. State Department report. “These reins will be picked up either by the United States or by Russia.” The United States was wedded to the notion — dating to the Wilson administration — that communism and capitalism were incompatible on the world stage. With Britain faltering, American officials saw little choice but to fill its shoes.

It did not take long for the reality of Britain’s decline to resonate across the Atlantic. In February 1947, London informed Truman that it could no longer afford to support the anticommunists in the Greek civil war. Truman worried that a communist victory in Greece would lead to Soviet domination of the eastern Mediterranean and embolden Communist parties in France and Italy. In response, the president announced what became known as the Truman Doctrine. In a speech on March 12, he asserted an American responsibility “to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” To that end, Truman proposed large-scale assistance for Greece and Turkey (then involved in a dispute with the Soviet Union over the Dardanelles, a strait connecting the Aegean Sea and the Sea of Marmara). “If we falter in our leadership, we may endanger the peace of the world,” Truman declared (Thinking Like a Historian). Despite the open-endedness of this military commitment, Congress quickly approved Truman’s request for $300 million in aid to Greece and $100 million for Turkey.

Soviet expansionism was part of a larger story. Europe was sliding into economic chaos. Already devastated by the war, in 1947 the continent suffered the worst winter in memory. People were starving, credit was nonexistent, wages were stagnant, and the consumer market had collapsed. For both humanitarian and practical reasons, Truman’s advisors believed something had to be done. A global depression might ensue if the European economy, the largest foreign market for American goods, did not recover. Worse, unemployed and dispirited Western Europeans might fill the ranks of the Communist Party, threatening political stability and the legitimacy of the United States. Secretary of State George C. Marshall came up with a remarkable proposal: a massive infusion of American capital to rebuild the European economy. Speaking at the Harvard University commencement in June 1947, Marshall urged the nations of Europe to work out a comprehensive recovery program based on U.S. aid.

This pledge of financial assistance required congressional approval, but the plan ran into opposition in Washington. Republicans castigated the Marshall Plan as a huge “international WPA.” But in the midst of the congressional stalemate, on February 25, 1948, Stalin supported a communistled coup in Czechoslovakia. Congress rallied and voted overwhelmingly in 1948 to approve the Marshall Plan. Over the next four years, the United States contributed nearly $13 billion to a highly successful recovery effort that benefitted both Western Europe and the United States. European industrial production increased by 64 percent, and the appeal of Communist parties waned in the West. Markets for American goods grew stronger and fostered economic interdependence between Europe and the United States. Notably, however, the Marshall Plan intensified Cold War tensions. U.S. officials invited the Soviets to participate but insisted on certain restrictions that would virtually guarantee Stalin’s refusal. When Stalin refused, ordering Soviet client states to do so as well, the onus of dividing Europe appeared to fall on the Soviet leader and deprived his threadbare partners of assistance they sorely needed.

East and West in the New Europe The flash point for a hot war remained Germany, the most important industrial economy and the key strategic landmass in Europe. When no agreement could be reached to unify the four zones of occupation into a single state, the Western allies consolidated their three zones in 1947. They then prepared to establish an independent federal German republic. Marshall Plan funds would jump-start economic recovery. Some of those funds were slated for West Berlin, in hopes of making the city a capitalist showplace 100 miles deep inside the Soviet zone.

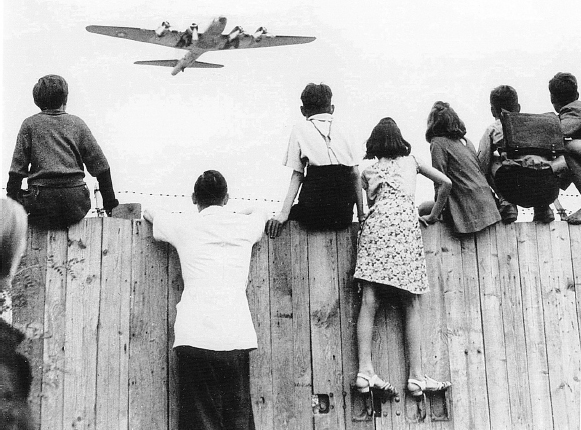

Stung by the West’s intention to create a German republic, in June 1948 Stalin blockaded all traffic to West Berlin. Instead of yielding, as Stalin had expected, Truman and the British were resolute. “We are going to stay, period,” Truman said plainly. Over the next year, American and British pilots, who had been dropping bombs on Berlin only four years earlier, improvised the Berlin Airlift, which flew 2.5 million tons of food and fuel into the Western zones of the city — nearly a ton for each resident. Military officials reported to Truman that General Lucius D. Clay, the American commander in Berlin, was nervous and on edge, “drawn as tight as a steel spring.” But after a prolonged stalemate, Stalin backed down: on May 12, 1949, he lifted the blockade. Until the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, the Berlin crisis was the closest the two sides came to actual war, and West Berlin became a symbol of resistance to communism.

The crisis in Berlin persuaded Western European nations to forge a collective security pact with the United States. In April 1949, for the first time since the end of the American Revolution, the United States entered into a peacetime military alliance, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Under the NATO pact, twelve nations — Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Great Britain, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, and the United States — agreed that “an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all.” In May 1949, those nations also agreed to the creation of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), which eventually joined NATO in 1955. In response, the Soviet Union established the German Democratic Republic (East Germany); the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON); and, in 1955, the Warsaw Pact, a military alliance for Eastern Europe that included Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and the Soviet Union. In these parallel steps, the two superpowers had institutionalized the Cold War through a massive division of the continent.

By the early 1950s, West and East were the stark markers of the new Europe. As Churchill had observed in 1946, the line dividing the two stretched “from Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic,” cutting off tens of millions of Eastern Europeans from the rest of the continent. Stalin’s tactics had often been ruthless, but they were not without reason. The Soviet Union acted out of the sort of self-interest that had long defined powerful nations — ensuring a defensive perimeter of allies, seeking access to raw materials, and pressing the advantage that victory in war allowed.

NSC-68 Atomic developments, too, played a critical role in the emergence of the Cold War. As the sole nuclear power at the end of World War II, the United States entertained the possibility of international control of nuclear technology but did not wish to lose its advantage over the Soviet Union. When the American Bernard Baruch proposed United Nations oversight of atomic energy in 1946, for instance, the plan assured the United States of near-total control of the technology, which further increased Cold War tensions. America’s brief tenure as sole nuclear power ended in September 1949, however, when the Soviet Union detonated an atomic bomb. Truman then turned to the U.S. National Security Council (NSC), established by the National Security Act of 1947, for a strategic reassessment.

In April 1950, the NSC delivered its report, known as NSC-68. Bristling with alarmist rhetoric, the document marked a decisive turning point in the U.S. approach to the Cold War. The report’s authors described the Soviet Union not as a typical great power but as one with a “fanatic faith” that seeks to “impose its absolute authority.” Going beyond even the stern language used by George Kennan, NSC-68 cast Soviet ambitions as nothing short of “the domination of the Eurasian landmass.”

To prevent that outcome, the report proposed “a bold and massive program of rebuilding the West’s defensive potential to surpass that of the Soviet world” (America Compared). This included the development of a hydrogen bomb, a thermonuclear device that would be a thousand times more destructive than the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, as well as dramatic increases in conventional military forces. Critically, NSC-68 called for Americans to pay higher taxes to support the new military program and to accept whatever sacrifices were necessary to achieve national unity of purpose against the Soviet enemy. Many historians see the report as having “militarized” the American approach to the Cold War, which had to that point relied largely on economic measures such as aid to Greece and the Marshall Plan. Truman was reluctant to commit to a major defense buildup, fearing that it would overburden the national budget. But shortly after NSC-68 was completed, events in Asia led him to reverse course.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

Why did the United States enact the Marshall Plan, and how did the program illustrate America’s new role in the world?