America’s History: Printed Page 850

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 772

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 753

The Baby Boom

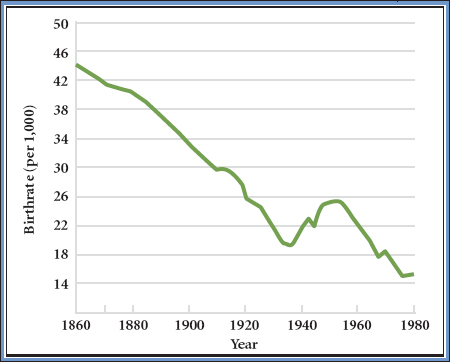

A popular 1945 song was called “Gotta Make Up for Lost Time,” and Americans did just that. Two things were noteworthy about the families they formed after World War II: First, marriages were remarkably stable. Not until the mid-1960s did the divorce rate begin to rise sharply. Second, married couples were intent on having babies. Everyone expected to have several children — it was part of adulthood, almost a citizen’s responsibility. After a century and a half of decline, the birthrate shot up. More babies were born in the six years between 1948 and 1953 than in the previous thirty years (Figure 26.3).

One of the reasons for this baby boom was that people were having children at the same time. A second was a drop in the average marriage age — down to twenty-two for men and twenty for women. Younger parents meant a bumper crop of children. Women who came of age in the 1930s averaged 2.4 children; their counterparts in the 1950s averaged 3.2 children. Such a dramatic turnaround reflected couples’ decisions during the Great Depression to limit childbearing and couples’ contrasting decisions in the postwar years to have more children. The baby boom peaked in 1957 and remained at a high level until the early 1960s. Far from “normal,” all of these developments were anomalies, temporary reversals of long-standing demographic trends. From the perspective of the whole of the twentieth century, the 1950s and early 1960s stand out as exceptions to declining birthrates, rising divorce rates, and the steadily rising marriage age.

The passage of time revealed the ever-widening impact of the baby boom. When baby boomers competed for jobs during the 1970s, the labor market became tight. When career-oriented baby boomers belatedly began having children in the 1980s, the birthrate jumped. And in our own time, as baby boomers begin retiring, huge funding problems threaten to engulf Social Security and Medicare. The intimate decisions of so many couples after World War II continued to shape American life well into the twenty-first century.

Improving Health and Education Baby boom children benefitted from a host of important advances in public health and medical practice in the postwar years. Formerly serious illnesses became merely routine after the introduction of such “miracle drugs” as penicillin (introduced in 1943), streptomycin (1945), and cortisone (1946). When Dr. Jonas Salk perfected a polio vaccine in 1954, he became a national hero. The free distribution of Salk’s vaccine in the nation’s schools, followed in 1961 by Dr. Albert Sabin’s oral polio vaccine, demonstrated the potential of government-sponsored public health programs.

The baby boom also gave the nation’s educational system a boost. Postwar middle-class parents, America’s first college-educated generation, placed a high value on education. Suburban parents approved 90 percent of school bond issues during the 1950s. By 1970, school expenditures accounted for 7.2 percent of the gross national product, double the 1950 level. In the 1960s, the baby boom generation swelled college enrollments. State university systems grew in tandem: the pioneering University of California, University of Wisconsin, and State University of New York systems added dozens of new campuses and offered students in their states a low-cost college education.

Dr. Benjamin Spock To keep baby boom children healthy and happy, middle-class parents increasingly relied on the advice of experts. Dr. Benjamin Spock’s Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care sold 1 million copies every year after its publication in 1946. Spock urged mothers to abandon the rigid feeding and baby-care schedules of an earlier generation. New mothers found Spock’s commonsense approach liberating. “Your little paperback is still in my cupboard, with loose pages, rather worn from use because I brought up two babies using it as my ‘Bible,’” a California housewife wrote to Spock.

Despite his commonsense approach to child rearing, Spock was part of a generation of psychological experts whose advice often failed to reassure women. If mothers were too protective, Spock and others argued, they might hamper their children’s preparation for adult life. On the other hand, mothers who wanted to work outside the home felt guilty because Spock recommended that they be constantly available for their children. As American mothers aimed for the perfection demanded of them seemingly at every turn, many began to question these mixed messages. Some of them would be inspired by the resurgence of feminism in the 1960s.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

Why was there an increase in births in the decades after World War II, and what were some of the effects of this baby boom?