America’s History: Printed Page 852

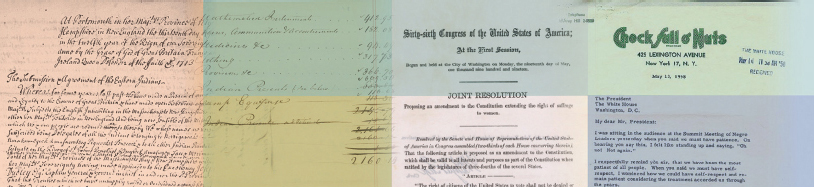

AMERICAN VOICES |  |

Coming of Age in the Postwar Years

At the dawn of the postwar era, Americans faced new opportunities and new anxieties. Many former soldiers attended college and purchased new homes on the GI Bill, which forever changed their lives. Women faced new pressures to realize the ideal role of housewife and mother. On the horizon, both in reality and in the American imagination, lurked communism, which Americans feared but little understood. And racial segregation continued to shape the ordinary lives of Americans. Recorded here are several different reactions to these postwar tensions, distinct experiences of coming of age in the 1940s and 1950s.

Art Buchwald

Studying on the GI Bill

Art Buchwald was one of the best-known humorists in American journalism. But in 1946, he was an ordinary ex-serviceman using the GI Bill to go to college.

It was time to face up to whether I was serious about attending school. My decision was to go down to the University of Southern California and find out what I should study at night to get into the place. There were at least 4,000 ex-GIs waiting to register. I stood in line with them. Hours later, I arrived at the counter and said, “I would like to … ” The clerk said, “Fill this out.”

Having been accepted as a full-time student under the G.I. Bill, I was entitled to seventy-five dollars a month plus tuition, books, and supplies. Meanwhile, I found a boardinghouse a few blocks from campus, run by a cheery woman who was like a mother to her thirteen boarders. … At the time, just after the Second World War had ended, an undeclared class war was going on at USC. The G.I.s returning home had little use for the fraternity men, since most of the frat boys were not only much younger, but considered very immature.

The G.I.s were intent on getting their educations and starting new lives.

Source: From Leaving Home: A Memoir, by Art Buchwald (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1993). Used by permission of Joel Buchwald.

Betty Friedan

Living the Feminine Mystique

Like Buchwald, Betty Friedan would one day become famous as a writer — author of one of the most widely read books of the 1960s, The Feminine Mystique. In the late 1940s, Friedan was not yet a feminist, but she was deeply engaged in the politics of the era.

And then the boys our age had come back from the war. I was bumped from my job on a small labor news service by a returning veteran, and it wasn’t so easy to find another job I really liked. I filled out the applications for Time-Life researcher, which I’d always scorned before. All the girls I knew had jobs like that, but it was official policy that no matter how good, researchers, who were women, could never become writers or editors. They could write the whole article, but the men they were working with would always get the by-line as writer. I was certainly not a feminist then — none of us were a bit interested in women’s rights. But I could never bring myself to take that kind of job.

After the war, I had been very political, very involved, consciously radical. Not about women, for heaven’s sake! If you were a radical in 1949, you were concerned about the Negroes, and the working class, and World War III, and the Un-American Activities Committee and McCarthy and loyalty oaths, and Communist splits and schisms, Russia, China and the UN, but you certainly didn’t think about being a woman, politically.

Source: From “It Changed My Life”: Writings on the Women’s Movement, by Betty Friedan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976). Copyright © 1963 by Betty Friedan. Reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd.

Susan Allen Toth

Learning About Communism

Toth is a writer who grew up in Ames, Iowa, surrounded by cornfields. She writes here about her experience learning just how anxious people could become in the 1950s when the issue of communism was raised.

Of course, we all knew there was Communism. As early as sixth grade our teacher warned us about its dangers. I listened carefully to Mr. Casper describe what Communists wanted, which sounded terrible. World domination. Enslavement. Destruction of our way of life. I hung around school one afternoon hoping to catch Mr. Casper, whom I secretly adored, to ask him why Communism was so bad. He stayed in another teacher’s room so late I finally scrawled my question on our blackboard: “Dear Mr. Casper, why is Communism so bad … Sue Allen” and went home. Next morning the message was still there. Like a warning from heaven it had galvanized Mr. Casper. He began class with a stern lecture, repeating everything he had said about dangerous Russians and painting a vivid picture of how we would all suffer if the Russians took over the city government in Ames. We certainly wouldn’t be able to attend a school like this, he said, where free expression of opinion was allowed. At recess that day one of the boys asked me if I was a “dirty Commie”: two of my best friends shied away from me on the playground; I saw Mr. Casper talking low to another teacher and pointing at me. I cried all the way home from school and resolved never to commit myself publicly with a question like that again.

Source: From Susan Allen Toth, “Boyfriend” from Blooming: A Small-Town Girlhood. Reprinted by permission of Molly Friedrich on behalf of the author.

Melba Patillo Beals

Encountering Segregation

Melba Patillo Beals was one of the “Little Rock Nine,” the high school students who desegregated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957. Here she recounts an experience documenting what it was like to come of age as a black southerner under Jim Crow.

An experience I endured on a December morning would forever affect any decision I made to go “potty” in a public place. We were Christmas shopping when I felt the twinge of emergency. I convinced Mother and Grandmother that I knew the way to restroom by myself. I was moving as fast as I could when suddenly I knew I wasn’t going to make it all the way down those stairs and across the warehouse walkway to the “Colored Ladies” toilet. So I pushed open the door marked “White Ladies” and, taking a deep breath, I crossed the threshold. It was just as bright and pretty as I had imagined it to be. … Across the room, other white ladies sat on a couch reading the newspaper. Suddenly realizing I was there, two of them looked at me in astonishment. Unless I was the maid, they said, I was in the wrong place. While they shouted at me to “get out,” my throbbing bladder consumed my attention as I frantically headed for the unoccupied stall. They kept shouting “Good lord, do something.” I was doing something by that time, seated comfortably on the toilet, listening to the hysteria building outside my locked stall. One woman even knelt down to peep beneath the door to make certain that I didn’t put my bottom on the toilet seat. She ordered me not to pee.

Source: Reprinted with permission of Atria Publishing Group, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Warriors Don’t Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock by Melba Patillo Beals. Copyright © 1994, 1995 by Melba Beals. All rights reserved.

David Beers

California Suburbia

David Beers grew up in the suburbs of California, in what would eventually become known as Silicon Valley. In his memoir, he recalls the ritual of buying a house.

“We never looked at a used house,” my father remembers of those days in the early 1960s when he and my mother went shopping for a home of their own in the Valley of Heart’s Delight. “A used house did not interest us.” Instead, they roved in search of balloons and bunting and the many billboards advertising Low Interest! No Money Down! to military veterans like my father. They would follow the signs to the model homes standing in empty fields and tour the empty floor plans and leave with notes carefully made about square footage and closet space. “We shopped for a new house,” my father says, “the way you shopped for a car.” … We were blithe conquerors, my tribe. When we chose a new homeland, invaded a place, settled it, and made it over in our image, we did so with a smiling sense of our own inevitability. … We were drawn to the promise of a blank page inviting our design upon it.

Source: David Beers, Blue Sky Dream: A Memoir of America’s Fall from Grace (New York: Harcourt, Brace, & Company, 1996), 31, 39.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

Question

What do you think Buchwald meant by “an undeclared class war”? Why would the influx of GI Bill veterans into colleges create conflict?

Question

Why do you think Friedan “didn’t think about being a woman, politically” in the 1940s and 1950s? Why do you think she was “bumped from” her job by a “returning veteran”?

Question

What does Toth’s experience as a young student suggest about American anxieties during the Cold War? Why would her question cause embarrassment and ridicule?

Question

What does Beals’s experience suggest about the indignities faced by young people on the front lines of challenging racial segregation? Does it help explain why youth were so important in breaking racial barriers?

Question

What do you think Beers means by “our tribe”? What was the “blank page”?