America: A Concise History: Printed Page 775

Concise Edition |  |

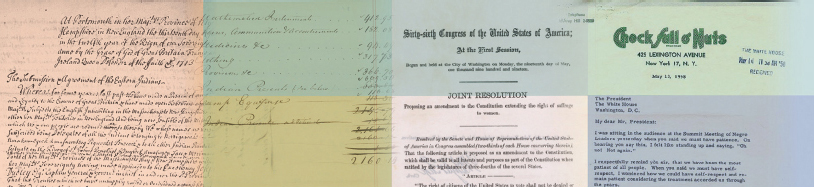

AMERICAN VOICES |

Coming of Age in the Postwar Years

At the dawn of the postwar era, Americans faced new opportunities and new anxieties. Many former soldiers attended college and purchased new homes on the GI Bill, which forever changed their lives, and women faced new pressures to realize the ideal role of housewife and mother.

Art Buchwald

Studying on the GI Bill

Art Buchwald was one of the best-known humorists in American journalism in the 1950s and 1960s, and his column in the Washington Post was widely reprinted. But in 1946, he was an ordinary ex-serviceman hoping to use the GI Bill to go to college.

It was time to face up to whether I was serious about attending school. My decision was to go down to the University of Southern California and find out what I should study at night to get into the place. There were at least 4,000 ex-GIs waiting to register. I stood in line with them. Hours later, I arrived at the counter and said, “I would like to …” The clerk said, “Fill this out.”

Having been accepted as a full-time student under the G.I. Bill, I was entitled to seventy-five dollars a month plus tuition, books, and supplies. Meanwhile, I found a boardinghouse a few blocks from campus, run by a cheery woman who was like a mother to her thirteen boarders. … At the time, just after the Second World War had ended, an undeclared class war was going on at USC. The G.I.s returning home had little use for the fraternity men, since most of the frat boys were not only much younger, but considered very immature.

The G.I.s were intent on getting their educations and starting new lives. Some fraternity people partied, drank, cheated on tests, and tried to take over school politics. In those days, the administration catered to the fraternities, knowing that eventually they would be the big financial supporters of the school, as opposed to the independents, who would probably not be heard from again.

It wasn’t my first decision to favor the have-nots over the haves. I had been doing it all my life.

Source : Art Buchwald, Leaving Home: A Memoir (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1993), 201–205.

Betty Friedan

Living the Feminine Mystique

Like Buchwald, Betty Friedan would one day become famous as a writer — as a feminist who wrote one of the most widely read books of the 1960s, The Feminine Mystique. In the late 1940s, Friedan was not yet a feminist, but she was deeply engaged in the politics of the era

And then the boys our age had come back from the war. I was bumped from my job on a small labor news service by a returning veteran, and it wasn’t so easy to find another job I really liked. I filled out the applications for Time-Life researcher, which I’d always scorned before. All the girls I knew had jobs like that, but it was official policy that no matter how good, researchers, who were women, could never become writers or editors. They could write the whole article, but the men they were working with would always get the by-line as writer. I was certainly not a feminist then — none of us were a bit interested in women’s rights. But I could never bring myself to take that kind of job.

After the war, I had been very political, very involved, consciously radical. Not about women, for heaven’s sake! If you were a radical in 1949, you were concerned about the Negroes, and the working class, and World War III, and the Un-American Activities Committee and McCarthy and loyalty oaths, and Communist splits and schisms, Russia, China and the UN, but you certainly didn’t think about being a woman, politically. It was only recently that we had begun to think of ourselves as women at all. But that wasn’t political — it was the opposite of politics.

Source : Betty Friedan, “It Changed My Life”: Writings on the Women’s Movement (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976). Copyright (c) 1963 by Betty Friedan. Reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd.