America’s History: Printed Page 856

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 778

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 758

The Postwar Housing Boom

Migration to the suburbs had been going on for a hundred years, but never before on the scale that the country experienced after World War II. Within a decade, farmland on the outskirts of cities filled up with tract housing and shopping malls. Entire counties that had once been rural — such as San Mateo, south of San Francisco, or Passaic and Bergen in New Jersey, west of Manhattan — went suburban. By 1960, one-third of Americans lived in suburbs. Home construction, having ground to a halt during the Great Depression, surged after the war. One-fourth of the country’s entire housing stock in 1960 had not even existed a decade earlier.

William J. Levitt and the FHA Two unique postwar developments remade the national housing market and gave it a distinctly suburban shape. First, an innovative Long Island building contractor, William J. Levitt, revolutionized suburban housing by applying mass-production techniques and turning out new homes at a dizzying speed. Levitt’s basic four-room house, complete with kitchen appliances, was priced at $7,990 when homes in the first Levittown went on sale in 1947 (about $76,000 today). Levitt did not need to advertise; word of mouth brought buyers flocking to his developments (all called Levittown) in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. Dozens of other developers were soon snapping up cheap farmland and building subdivisions around the country.

Even at $7,990, Levitt’s homes would have been beyond the means of most young families had the traditional home-financing standard — a down payment of half the full price and ten years to pay off the balance — still prevailed. That is where the second postwar development came in. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Veterans Administration (VA) — that is, the federal government — brought the home mortgage market within the reach of a broader range of Americans than ever before. After the war, the FHA insured thirty-year mortgages with as little as 5 percent down and interest at 2 or 3 percent. The VA was even more generous, requiring only a token $1 down for qualified ex-GIs. FHA and VA mortgages best explain why, after hovering around 45 percent for the previous half century, home ownership jumped to 60 percent by 1960.

What purchasers of suburban houses got, in addition to a good deal, were homogeneous communities. The developments contained few elderly people or unmarried adults. Even the trees were young. Levitt’s company enforced regulations about maintaining lawns and not hanging out laundry on the weekends. Then there was the matter of race. Levitt’s houses came with restrictive covenants prohibiting occupancy “by members of other than the Caucasian Race.” (Restrictive covenants often applied to Jews and, in California, Asian Americans as well.) Levittowns were hardly alone. Suburban developments from coast to coast exhibited the same age, class, and racial homogeneity (Thinking Like a Historian).

In Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), the Supreme Court outlawed restrictive covenants, but racial discrimination in housing changed little. The practice persisted long after Shelley, because the FHA and VA continued the policy of redlining: refusing mortgages to African Americans and members of other minority groups seeking to buy in white neighborhoods. Indeed, no federal law — or even Court decisions like Shelley — actually prohibited racial discrimination in housing until Congress passed the Fair Housing Act in 1968.

Interstate Highways Without automobiles, suburban growth on such a massive scale would have been impossible. Planners laid out subdivisions on the assumption that everybody would drive. And they did — to get to work, to take the children to Little League, to shop. With gas plentiful and cheap (15 cents a gallon), no one cared about the fuel efficiency of their V-8 engines or seemed to mind the elaborate tail fins and chrome that weighed down their cars. In 1945, Americans owned twenty-five million cars; by 1965, just two decades later, the number had tripled to seventy-five million (America Compared). American oil consumption followed course, tripling as well between 1949 and 1972.

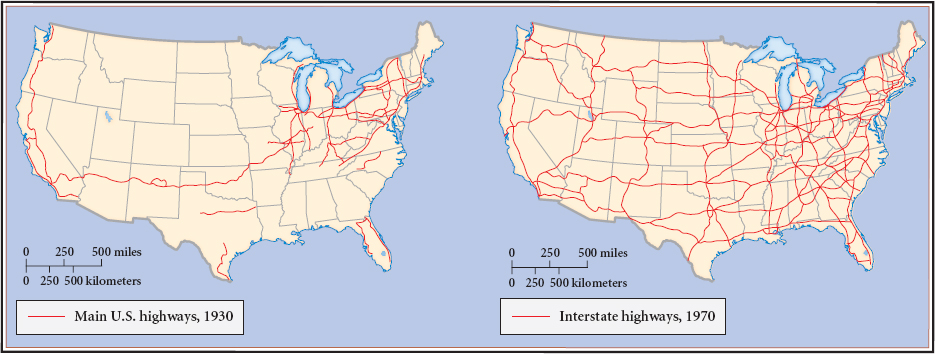

More cars required more highways, and the federal government obliged. In 1956, in a move that drastically altered America’s landscape and driving habits, the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act authorized $26 billion over a ten-year period for the construction of a nationally integrated highway system — 42,500 miles (Map 26.1). Cast as a Cold War necessity because broad highways made evacuating crowded cities easier in the event of a nuclear attack, the law changed American cities forever. An enormous public works program surpassing anything undertaken during the New Deal, and enthusiastically endorsed by the Republican president, Dwight Eisenhower, federal highways made possible the massive suburbanization of the nation in the 1960s. Interstate highways rerouted traffic away from small towns, bypassed well-traveled main roads such as the cross-country Route 66, and cut wide swaths through old neighborhoods in the cities.

Fast Food and Shopping Malls Americans did not simply fill their new suburban homes with the latest appliances and gadgets; they also pioneered entirely new forms of consumption. Through World War II, downtowns had remained the center of retail sales and restaurant dining with their grand department stores, elegant eateries, and low-cost diners. As suburbanites abandoned big-city centers in the 1950s, ambitious entrepreneurs invented two new commercial forms that would profoundly shape the rest of the century: the shopping mall and the fast-food restaurant.

By the late 1950s, the suburban shopping center had become as much a part of the American landscape as the Levittowns and their imitators. A major developer of shopping malls in the Northeast called them “crystallization points for suburbia’s community life.” He romanticized the new structures as “today’s village green,” where “the fountain in the mall has replaced the downtown department clock as the gathering place for young and old alike.” Romanticism aside, suburban shopping centers worked perfectly in the world of suburban consumption; they brought “the market to the people instead of people to the market,” commented the New York Times. In 1939, the suburban share of total metropolitan retail trade in the United States was a paltry 4 percent. By 1961, it was an astonishing 60 percent in the nation’s ten largest metropolitan regions.

No one was more influential in creating suburban patterns of consumption than a Chicago-born son of Czech immigrants named Ray Kroc. A former jazz musician and traveling salesman, Kroc found his calling in 1954 when he acquired a single franchise of the little-known McDonald’s Restaurant, based in San Bernardino, California. In 1956, Kroc invested in twelve more franchises and by 1958 owned seventy-nine. Three years later, Kroc bought the company from the McDonald brothers and proceeded to turn it into the largest chain of restaurants in the world. Based on inexpensive, quickly served hamburgers that hungry families could eat in the restaurant, in their cars, or at home, Kroc’s vision transformed the way Americans consumed food. “Drive-in” or “fast” food became a staple of the American diet in the subsequent decades. By the year 2000, fast food was a $100 billion industry, and more children recognized Ronald McDonald, the clown in McDonald’s television commercials, than Santa Claus.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

Place postwar suburbanization in the context of the growing size and influence of the federal government. How did the national government encourage suburbanization?