America’s History: Printed Page 840

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 762

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 741

Economy: From Recovery to Dominance

U.S. corporations, banks, and manufacturers so dominated the global economy that the postwar period has been called the Pax Americana (a Latin term meaning “American Peace” and harking back to the Pax Romana of the first and second centuries A.D.). Life magazine publisher Henry Luce was so confident in the nation’s growing power that during World War II he had predicted the dawning of the “American century.” The preponderance of American economic power in the postwar decades, however, was not simply an artifact of the world war — it was not an inevitable development. Several key elements came together, internationally and at home, to propel three decades of unprecedented economic growth.

The Bretton Woods System American global supremacy rested partly on the economic institutions created at an international conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in July 1944. The first of those institutions was the World Bank, created to provide loans for the reconstruction of war-torn Europe as well as for the development of former colonized nations — the so-called Third World or developing world. A second institution, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), was set up to stabilize currencies and provide a predictable monetary environment for trade, with the U.S. dollar serving as the benchmark. The World Bank and the IMF formed the cornerstones of the Bretton Woods system, which guided the global economy after the war.

The Bretton Woods system was joined in 1947 by the first General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which established an international framework for overseeing trade rules and practices. Together, the Bretton Woods system and GATT served America’s conception of an open-market global economy and complemented the nation’s ambitious diplomatic aims in the Cold War. The chief idea of the Bretton Woods system was to make American capital available, on cheap terms, to nations that adopted free-trade capitalist economies. Critics charged, rightly, that Bretton Woods and GATT favored the United States at the expense of recently independent countries, because the United States could dictate lending terms and stood to benefit as nations purchased more American goods. But the system provided needed economic stability.

The Military-Industrial Complex A second engine of postwar prosperity was defense spending. In his final address to the nation in 1961, President Dwight D. Eisenhower spoke about the power of what he called the military-industrial complex, which by then employed 3.5 million Americans. Even though his administration had fostered this defense establishment, Eisenhower feared its implications: “We must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” he said. This complex had its roots in the business-government partnerships of World War II. After 1945, though the country was nominally at peace, the economy and the government operated in a state of perpetual readiness for war.

Based at the sprawling Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, the Defense Department evolved into a massive bureaucracy. In the name of national security, defense-related industries entered into long-term relationships with the Pentagon. Some companies did so much business with the government that they in effect became private divisions of the Defense Department. Over 60 percent of the income of Boeing, General Dynamics, and Raytheon, for instance, came from military contracts, and the percentages were even higher for Lockheed and Republic Aviation. In previous peacetime years, military spending had constituted only 1 percent of gross domestic product (GDP); now it represented 10 percent. Economic growth was increasingly dependent on a robust defense sector.

As permanent mobilization took hold, science, industry, and government became intertwined. Cold War competition for military supremacy spawned both an arms race and a space race as the United States and the Soviet Union each sought to develop more explosive bombs and more powerful rockets. Federal spending underwrote 90 percent of the cost of research for aviation and space, 65 percent for electricity and electronics, 42 percent for scientific instruments, and even 24 percent for automobiles. With the government footing the bill, corporations lost little time in transforming new technology into useful products. Backed by the Pentagon, for instance, IBM and Sperry Rand pressed ahead with research on integrated circuits, which later spawned the computer revolution.

When the Soviet Union launched the world’s first satellite, Sputnik, in 1957, the startled United States went into high gear to catch up in the Cold War space competition. Alarmed that the United States was falling behind in science and technology, Eisenhower persuaded Congress to appropriate additional money for college scholarships and university research. The National Defense Education Act of 1958 funneled millions of dollars into American universities, helping institutions such as the University of California at Berkeley, Stanford University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the University of Michigan become the leading research centers in the world.

Corporate Power Despite its massive size, the military-corporate partnership was only one part of the nation’s economy. For over half a century, the consolidation of economic power into large corporate firms had characterized American capitalism. In the postwar decades, that tendency accelerated. By 1970, the top four U.S. automakers produced 91 percent of all motor vehicles sold in the country; the top four firms in tires produced 72 percent; those in cigarettes, 84 percent; and those in detergents, 70 percent. Eric Johnston, former president of the American Chamber of Commerce, declared that “we have entered a period of accelerating bigness in all aspects of American life.” Expansion into foreign markets also spurred corporate growth. During the 1950s, U.S. exports nearly doubled, giving the nation a trade surplus of close to $5 billion in 1960. By the 1970s, such firms as Coca-Cola, Gillette, IBM, and Mobil made more than half their profits abroad.

To staff their bureaucracies, the postwar corporate giants required a huge white-collar army. A new generation of corporate chieftains emerged, operating in a complex environment that demanded long-range forecasting. Companies turned to the universities, which grew explosively after 1945. Postwar corporate culture inspired numerous critics, who argued that the obedience demanded of white-collar workers was stifling creativity and blighting lives. In The Lonely Crowd (1950), the sociologist David Riesman mourned a lost masculinity and contrasted the independent businessmen and professionals of earlier years with the managerial class of the postwar world. The sociologist William Whyte painted a somber picture of “organization men” who left the home “spiritually as well as physically to take the vows of organization life.” Andrew Hacker, in The Corporation Take-Over (1964), warned that a small handful of such organization men “can draw up an investment program calling for the expenditure of several billions of dollars” and thereby “determine the quality of life for substantial segments of society.”

Many of these “investment programs” relied on mechanization, or automation — another important factor in the postwar boom. From 1947 to 1975, worker productivity more than doubled across the whole of the economy. American factories replaced manpower with machines, substituting cheap fossil energy for human muscle. As industries mechanized, they could turn out products more efficiently and at lower cost. Mechanization did not come without social costs, however. Over the course of the postwar decades, millions of high-wage manufacturing jobs were lost as machines replaced workers, affecting entire cities and regions. Corporate leaders approved, but workers and their union representatives were less enthusiastic. “How are you going to sell cars to all of these machines?” wondered Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers (UAW).

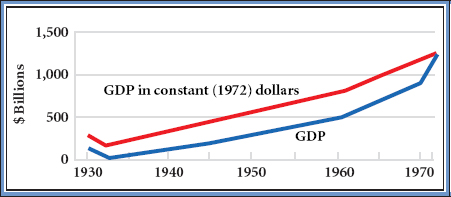

The Economic Record The American economy produced an extraordinary postwar record. Annual GDP jumped from $213 billion in 1945 to more than $500 billion in 1960; by 1970, it exceeded $1 trillion (Figure 26.1). This sustained economic growth meant a 25 percent rise in real income for ordinary Americans between 1946 and 1959. Even better, the new prosperity featured low inflation. After a burst of high prices in the immediate postwar period, inflation slowed to 2 to 3 percent annually, and it stayed low until the escalation of the Vietnam War in the mid-1960s. Feeling secure about the future, Americans were eager to spend and rightly felt that they were better off than ever before. In 1940, 43 percent of American families owned their homes; by 1960, 62 percent did. In that period, moreover, income inequality dropped sharply. The share of total income going to the top tenth — the richest Americans — declined by nearly one-third from the 45 percent it had been in 1940. American society had become not only more prosperous but also more egalitarian.

However, the picture was not as rosy at the bottom, where tenacious poverty accompanied the economic boom. In The Affluent Society (1958), which analyzed the nation’s successful, “affluent” middle class, economist John Kenneth Galbraith argued that the poor were only an “afterthought” in the minds of economists and politicians, who largely celebrated the new growth. As Galbraith noted, one in thirteen families at the time earned less than $1,000 a year (about $7,500 in today’s dollars). Four years later, in The Other America (1962), the left-wing social critic Michael Harrington chronicled “the economic underworld of American life,” and a U.S. government study, echoing a well-known sentence from Franklin Roosevelt’s second inaugural address (“I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished”), declared “one-third of the nation” to be poorly paid, poorly educated, and poorly housed. It appeared that in economic terms, as the top and the middle converged, the bottom remained far behind.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

What primary factors led to the growth of the American economy after World War II?