America’s History: Printed Page 843

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 765

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 745

A Nation of Consumers

The most breathtaking development in the postwar American economy was the dramatic expansion of the domestic consumer market. The sheer quantity of consumer goods available to the average person was without precedent. In some respects, the postwar decades seemed like the 1920s all over again, with an abundance of new gadgets and appliances, a craze for automobiles, and new types of mass media. Yet there was a significant difference: in the 1950s, consumption became associated with citizenship. Buying things, once a sign of personal indulgence, now meant participating fully in American society and, moreover, fulfilling a social responsibility. What the suburban family consumed, asserted Life magazine in a photo essay, would help to ensure “full employment and improved living standards for the rest of the nation.”

The GI Bill The new ethic of consumption appealed to the postwar middle class, the driving force behind the expanding domestic market. Middle-class status was more accessible than ever before because of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, popularly known as the GI Bill. In the immediate postwar years, more than half of all U.S. college students were veterans attending class on the government’s dime. By the middle of the 1950s, 2.2 million veterans had attended college and another 5.6 million had attended trade school with government financing. Before the GI Bill, commented one veteran, “I looked upon college education as likely as my owning a Rolls-Royce with a chauffeur.”

Government financing of education helped make the U.S. workforce the best educated in the world in the 1950s and 1960s. American colleges, universities, and trade schools grew by leaps and bounds to accommodate the flood of students — and expanded again when the children of those students, the baby boomers, reached college age in the 1960s. At Rutgers University, enrollment went from 7,000 before the war to 16,000 in 1947; at the University of Minnesota, from 15,000 to more than 27,000. The GI Bill trained nearly half a million engineers; 200,000 doctors, dentists, and nurses; and 150,000 scientists (among many other professions). Better education meant higher earning power, and higher earning power translated into the consumer spending that drove the postwar economy. One observer of the GI Bill was so impressed with its achievements that he declared it responsible for “the most important educational and social transformation in American history.”

The GI Bill stimulated the economy and expanded the middle class in another way: by increasing home ownership. Between the end of World War II and 1966, one of every five single-family homes built in the United States was financed through a GI Bill mortgage — 2.5 million new homes in all. In cities and suburbs across the country, the Veterans Administration (VA), which helped former soldiers purchase new homes with no down payment, sparked a building boom that created jobs in the construction industry and fueled consumer spending in home appliances and automobiles. Education and home ownership were more than personal triumphs for the families of World War II veterans (and Korean and Vietnam War veterans, after a new GI Bill was passed in 1952). They were concrete financial assets that helped lift more Americans than ever before into a mass-consumption-oriented middle class.

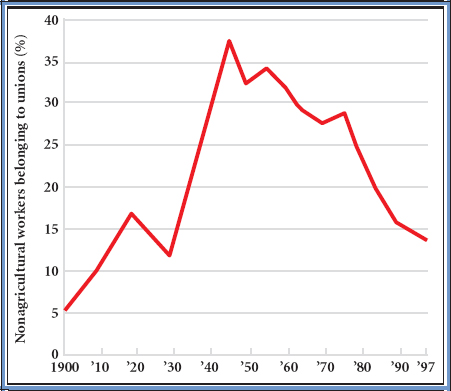

Trade Unions Organized labor also expanded the ranks of the middle class. For the first time ever, trade unions and collective bargaining became major factors in the nation’s economic life. In the past, organized labor had been confined to a narrow band of craft trades and a few industries, primarily coal mining, railroading, and the building and metal trades. The power balance shifted during the Great Depression, and by the time the dust settled after World War II, labor unions overwhelmingly represented America’s industrial workforce (Figure 26.2). By the beginning of the 1950s, the nation’s major industries, including auto, steel, clothing, chemicals, and virtually all consumer product manufacturing, were operating with union contracts.

That outcome did not arrive without a fight. Unions staged major strikes in nearly all American industries in 1945 and 1946, and employers fought back. Head of the UAW Walter Reuther and CIO president Philip Murray declared that employers could afford a 30 percent wage increase, which would fuel postwar consumption. When employers, led by the giant General Motors, balked at that demand, the two sides seemed set for a long struggle. Between 1947 and 1950, however, a broad “labor-management accord” gradually emerged across most industries. This was not industrial peace, because the country still experienced many strikes, but a general acceptance of collective bargaining as the method for setting the terms of employment. The result was rising real income. The average worker with three dependents gained 18 percent in spendable real income in the 1950s.

In addition, unions delivered greater leisure (more paid holidays and longer vacations) and, in a startling departure, a social safety net. In postwar Europe, America’s allies were constructing welfare states. But having lost the bruising battle in Washington for national health care during Truman’s presidency, American unions turned to the bargaining table. By the end of the 1950s, union contracts commonly provided pension plans and company-paid health insurance. Collective bargaining, the process of trade unions and employers negotiating workplace contracts, had become, in effect, the American alternative to the European welfare state and, as Reuther boasted, the passport into the middle class.

The labor-management accord, though impressive, was never as durable or universal as it seemed. Vulnerabilities lurked. For one thing, the sheltered domestic markets — the essential condition for generous contracts — were quite fragile. In certain industries, the lead firms were already losing market share. Second, generally overlooked were the many unorganized workers with no middle-class passport — those consigned to unorganized industries, casual labor, or low-wage jobs in the service sector. A final vulnerability was the most basic: the abiding antiunionism of American employers. At heart, managers regarded the labor-management accord as a negotiated truce, not a permanent peace. The postwar labor-management accord turned out to be a transitory event, not a permanent condition of American economic life.

Houses, Cars, and Children Increased educational levels, growing home ownership, and higher wages all enabled more Americans than ever before to become members of what one historian has called a “consumer republic.” But what did they buy? The postwar emphasis on nuclear families and suburbs provides the answer. In the emerging suburban nation, three elements came together to create patterns of consumption that would endure for decades: houses, cars, and children.

A feature in a 1949 issue of McCall’s, a magazine targeting middle-class women, illustrates the connections. “I now have three working centers,” a typical housewife explains. “The baby center, a baking center and a cleaning center.” Accompanying illustrations reveal the interior of the brand-new house, stocked with the latest consumer products: accessories for the baby’s room; a new stove, oven, and refrigerator; and a washer and dryer, along with cleaning products and other household goods. The article does not mention automobiles, but the photo of the house’s exterior makes the point clear: father drives home from work in a new car.

Consumption for the home, including automobiles, drove the postwar American economy as much as, or more than, the military-industrial complex did. If we think like advertisers and manufacturers, we can see why. Between 1945 and 1970, more than 25 million new houses were built in the United States. Each required its own supply of new appliances, from refrigerators to lawn mowers. In 1955 alone, Americans purchased 4 million new refrigerators, and between 1940 and 1951 the sale of power mowers increased from 35,000 per year to more than 1 million. Moreover, as American industry discovered planned obsolescence — the encouragement of consumers to replace appliances and cars every few years — the home became a site of perpetual consumer desire.

Children also encouraged consumption. The baby boomers born between World War II and the late 1950s have consistently, throughout every phase of their lives, been the darlings of American advertising and consumption. When they were infants, companies focused on developing new baby products, from disposable diapers to instant formula. When they were toddlers and young children, new television programs, board games, fast food, TV dinners, and thousands of different kinds of toys came to market to supply the rambunctious youth. When they were teenagers, rock music, Hollywood films, and a constantly marketed “teen culture” — with its appropriate clothing, music, hairstyles, and other accessories — bombarded them. Remarkably, in 1956, middle-class American teenagers on average had a weekly income of more than $10, close to the weekly disposable income of an entire family a generation earlier.

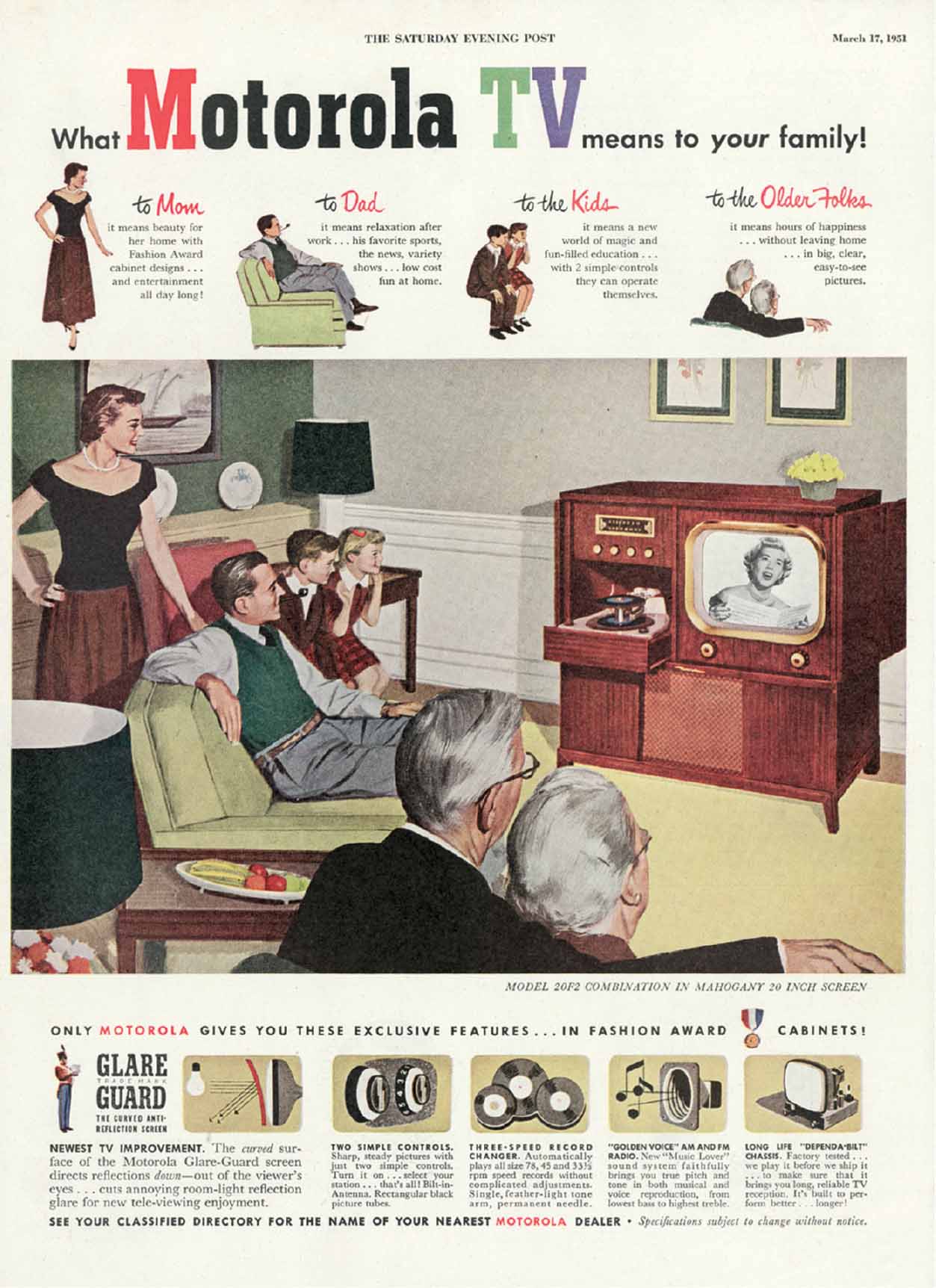

Television The emergence of commercial television in the United States was swift and overwhelming. In the realm of technology, only the automobile and the personal computer were its equal in transforming everyday life in the twentieth century. In 1947, there were 7,000 TV sets in American homes. A year later, the CBS and NBC radio networks began offering regular programming, and by 1950 Americans owned 7.3 million sets. Ten years later, 87 percent of American homes had at least one television set. Having conquered the home, television would soon become the principal mediator between the consumer and the marketplace.

Television advertisers mastered the art of manufacturing consumer desire. TV stations, like radio stations before them, depended entirely on advertising for profits. The first television executives understood that as long as they sold viewers to advertisers they would stay on the air. Early corporate-sponsored shows (such as General Electric Theater and U.S. Steel Hour) and simple product jingles (such as “No matter what the time or place, let’s keep up with that happy pace. 7-Up your thirst away!”) gave way by the early 1960s to slick advertising campaigns that used popular music, movie stars, sports figures, and stimulating graphics to captivate viewers.

By creating powerful visual narratives of comfort and plenty, television revolutionized advertising and changed forever the ways products were sold to American, and global, consumers. On Queen for a Day, a show popular in the mid-1950s, women competed to see who could tell the most heartrending story of tragedy and loss. The winner was lavished with household products: refrigerators, toasters, ovens, and the like. In a groundbreaking advertisement for Anacin aspirin, a tiny hammer pounded inside the skull of a headache sufferer. Almost overnight, sales of Anacin increased by 50 percent.

By the late 1950s, what Americans saw on television, both in the omnipresent commercials and in the programming, was an overwhelmingly white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant world of nuclear families, suburban homes, and middle-class life. A typical show was Father Knows Best, starring Robert Young and Jane Wyatt. Father left home each morning wearing a suit and carrying a briefcase. Mother was a full-time housewife and stereotypical female, prone to bad driving and tears. Leave It to Beaver, another immensely popular series about suburban family life, embodied similar late-fifties themes. Earlier in the decade, however, television featured grittier realities. The Honeymooners, starring Jackie Gleason as a Brooklyn bus driver, and The Life of Riley, a situation comedy featuring a California aircraft worker, treated working-class lives. Two other early-fifties television series, Beulah, starring Ethel Waters and then Louise Beavers as an African American maid, and the comedic Amos ’n’ Andy, were the only shows featuring black actors in major roles. Television was never a showcase for the breadth of American society, but in the second half of the 1950s broadcasting lost much of its ethnic, racial, and class diversity and became a vehicle for the transmission of a narrow range of middle-class tastes and values.

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES

Question

How did the tastes and values of the postwar middle class affect the country?