America’s History: Printed Page 877

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 798

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 778

Fighting for Equality Before the Law

With civil rights legislation blocked in Congress by southern Democrats throughout the 1950s, activists looked in two different directions for a breakthrough: to northern state legislatures and to the federal courts. School segregation remained a stubborn problem in northern states, but the biggest obstacle to black progress there was persistent job and housing discrimination. The states with the largest African American populations, and hence the largest share of black Democratic Party voters, became testing grounds for state legislation to end such discriminatory practices.

Winning antidiscrimination legislation depended on coalition politics. African American activists forged alliances with trade unions and liberal organizations such as the American Friends Service Committee (a Quaker group), among many others. Progress was slow and often occurred only after long periods of unglamorous struggle to win votes in state capitals such as Albany, New York; Springfield, Illinois; and Lansing, Michigan. The first fair employment laws had come in New York and New Jersey in 1945. A decade passed, however, before other states with significant black populations passed similar legislation. Antidiscrimination laws in housing were even more difficult to pass, with most progress not coming until the 1960s. These legislative campaigns in northern states received little national attention, but they were instrumental in laying the groundwork for legal equality outside the South.

Thurgood Marshall Because the vast majority of southern African Americans were prohibited from voting, state legislatures there were closed to the kind of organized political pressure possible in the North. Thus activists also looked to federal courts for leverage. In the late 1930s, NAACP lawyers Thurgood Marshall, Charles Hamilton Houston, and William Hastie had begun preparing the legal ground in a series of cases challenging racial discrimination. The key was prodding the U.S. Supreme Court to use the Fourteenth Amendment’s “equal protection” clause to overturn its 1896 ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld racial segregation under the “separate but equal” doctrine.

Marshall was the great-grandson of slaves. Of modest origins, his parents instilled in him a faith in law and the Constitution. After his 1930 graduation from Lincoln University, a prestigious African American institution near Philadelphia, Marshall applied to the University of Maryland Law School. Denied admission because the school did not accept black applicants, he enrolled at all-black Howard University. There Marshall met Houston, a law school dean, and the two forged a friendship and intellectual partnership that would change the face of American legal history. Marshall, with Houston’s and Hastie’s critical strategic input, would argue most of the NAACP’s landmark cases. In the late 1960s, President Johnson appointed Marshall to the Supreme Court — the first African American to have that honor.

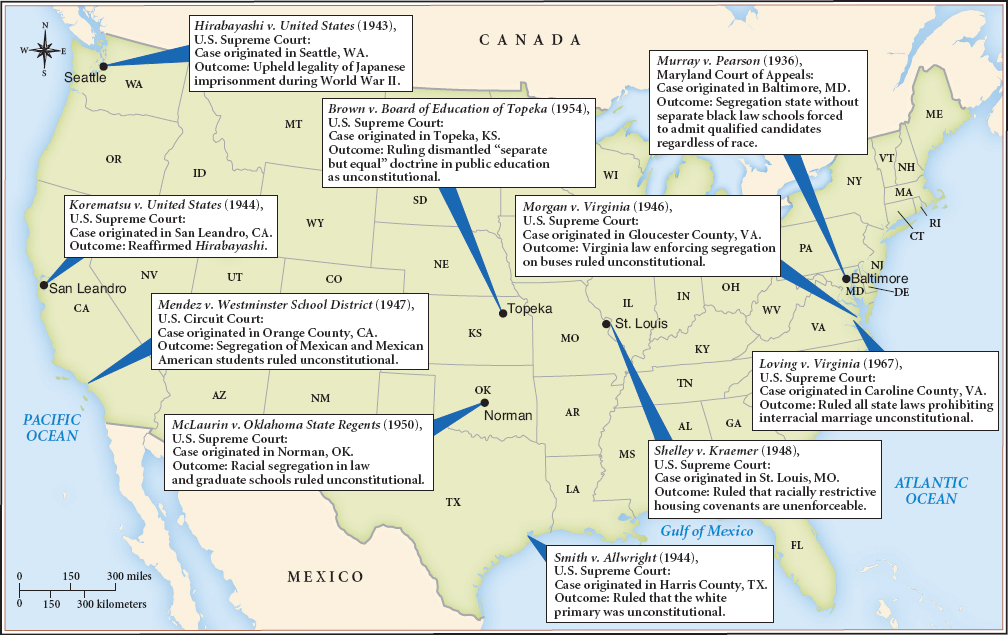

Marshall, Houston, Hastie, and six other attorneys filed suit after suit, deliberately selecting each one from dozens of possibilities. The strategy was slow and time-consuming, but progress came. In 1936, Marshall and Hamilton won a state case that forced the University of Maryland Law School to admit qualified African Americans — a ruling of obvious significance to Marshall. Eight years later, in Smith v. Allwright (1944), Marshall convinced the U.S. Supreme Court that all-white primaries were unconstitutional. In 1950, with Marshall once again arguing the case, the Supreme Court ruled in McLaurin v. Oklahoma that universities could not segregate black students from others on campus. None of these cases produced swift changes in the daily lives of most African Americans, but they confirmed that civil rights attorneys were on the right track.

Brown v. Board of Education The NAACP’s legal strategy achieved its ultimate validation in a case involving Linda Brown, a black pupil in Topeka, Kansas, who had been forced to attend a distant segregated school rather than the nearby white elementary school. In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), Marshall argued that such segregation was unconstitutional because it denied Linda Brown the “equal protection of the laws” guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment (Map 27.2). In a unanimous decision on May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court agreed, overturning the “separate but equal” doctrine at last. Writing for the Court, the new chief justice, Earl Warren, wrote: “We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” In an implementing 1955 decision known as Brown II, the Court declared simply that integration should proceed “with all deliberate speed.”

In the South, however, Virginia senator Harry F. Byrd issued a call for “massive resistance.” Calling May 17 “Black Monday,” the Mississippi segregationist Tom P. Brady invoked the language of the Cold War to discredit the decision, assailing the “totalitarian government” that had rendered the decision in the name of “socialism and communism.” That year, half a million southerners joined White Citizens’ Councils dedicated to blocking school integration. Some whites revived the old tactics of violence and intimidation, swelling the ranks of the Ku Klux Klan to levels not seen since the 1920s. The “Southern Manifesto,” signed in 1956 by 101 members of Congress, denounced the Brown decision as “a clear abuse of judicial power” and encouraged local officials to defy it. The white South had declared all-out war on Brown.

Enforcement of the Supreme Court’s decision was complicated further by Dwight Eisenhower’s presence in the White House — the president was no champion of civil rights. Eisenhower accepted the Brown decision as the law of the land, but he thought it a mistake. Ike was especially unhappy about the prospect of committing federal power to enforce the decision. A crisis in Little Rock, Arkansas, finally forced his hand. In September 1957, when nine black students attempted to enroll at the all-white Central High School, Governor Orval Faubus called out the National Guard to bar them. Angry white mobs appeared daily to taunt the students, chanting “Go back to the jungle.” As the vicious scenes played out on television night after night, Eisenhower finally acted. He sent 1,000 federal troops to Little Rock and nationalized the Arkansas National Guard, ordering them to protect the black students. Eisenhower thus became the first president since Reconstruction to use federal troops to enforce the rights of African Americans. But Little Rock also showed that southern officials had more loyalty to local custom than to the law — a repeated problem in the post-Brown era.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

How did the NAACP go about developing a legal strategy to attack racial segregation?