America’s History: Printed Page 880

THINKING LIKE A HISTORIAN |  |

Civil Rights and Black Power: Strategy and Ideology

The documents collected below reveal the range of perspectives and ideas at work within the broad civil rights, or “black freedom,” struggle in the 1960s.

Martin Luther King Jr., “If the Negro Wins, Labor Wins” speech, 1962. King, speaking to a meeting of the nation’s trade union leaders, explained the economic objectives of the black freedom struggle.

If we do not advance, the crushing burden of centuries of neglect and economic deprivation will destroy our will, our spirits and our hopes. In this way labor’s historic tradition of moving forward to create vital people as consumers and citizens has become our own tradition, and for the same reasons.

This unity of purpose is not an historical coincidence. Negroes are almost entirely a working people. There are pitifully few Negro millionaires and few Negro employers. Our needs are identical with labor’s needs: decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children and respect in the community. That is why Negroes support labor’s demands and fight laws which curb labor. …

The two most dynamic and cohesive liberal forces in the country are the labor movement and the Negro freedom movement. Together we can be architects of democracy in a South now rapidly industrializing.

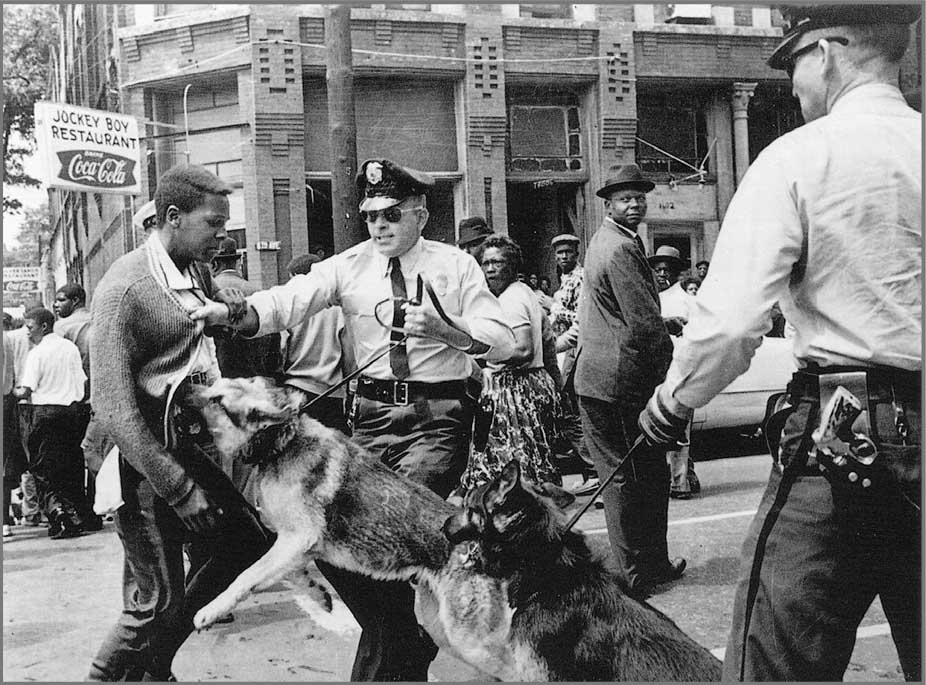

Police in Birmingham, Alabama, use trained German shepherds against peaceful African American protesters, 1963.

Bill Hudson / AP Images.

Bill Hudson / AP Images.Bayard Rustin, “From Protest to Politics,” Commentary, February 1965.

… it would be hard to quarrel with the assertion that the elaborate legal structure of segregation and discrimination, particularly in relation to public accommodations, has virtually collapsed. On the other hand, without making light of the human sacrifices involved in the direct-action tactics (sit-ins, freedom rides, and the rest) that were so instrumental to this achievement, we must recognize that in desegregating public accommodations, we affected institutions which are relatively peripheral both to the American socio-economic order and to the fundamental conditions of life of the Negro people. In a highly-industrialized, 20th-century civilization, we hit Jim Crow precisely where it was most anachronistic, dispensable, and vulnerable — in hotels, lunch counters, terminals, libraries, swimming pools, and the like. … At issue, after all, is not civil rights, strictly speaking, but social and economic conditions.

James Farmer, Freedom, When?, 1965.

“But when will the demonstrations end?” The perpetual question. And a serious question. Actually, it is several questions, for the meaning of the question differs, depending upon who asks it.

Coming from those whose dominant consideration is peace — public peace and peace of mind — the question means: “When are you going to stop tempting violence and rioting?” Some put it more strongly: “When are you going to stop sponsoring violence?” Assumed is the necessary connection between demonstration and violence. …

“Isn’t the patience of the white majority wearing thin? Why nourish the displeasure of 90 percent of the population with provocative demonstrations? Remember, you need allies.” And the assumptions of these Cassandras of the backlash is that freedom and equality are, in the last analysis, wholly gifts in the white man’s power to bestow. …

What the public must realize is that in a demonstration more things are happening, at more levels of human activity, than meets the eye. Demonstrations in the last few years have provided literally millions of Negroes with their first taste of self-determination and political self-expression.

Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America, 1967.

Black people must redefine themselves, and only they can do that. Throughout this country, vast segments of the black communities are beginning to recognize the need to assert their own definitions, to reclaim their history, their culture; to create their own sense of community and togetherness. There is a growing resentment of the word “Negro,” for example, because this term is the invention of our oppressor; it is his image of us that he describes. …

The concept of Black Power rests on a fundamental premise: Before a group can enter the open society, it must first close ranks. By this we mean that group solidarity is necessary before a group can operate effectively from a bargaining position of strength in a pluralistic society.

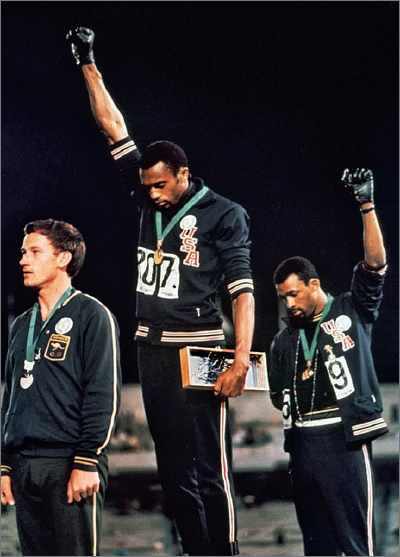

Black Power salute at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. Tommie Smith and John Carolos (right) won gold and bronze medals in the 200 meters. The silver medalist, Australian Peter Norman (left), is wearing an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge to show his support.

AP images.

AP images.

Sources: (1) “If the Negro Wins, Labor Wins,” by Martin Luther King delivered February 12, 1962. Reprinted by arrangement with the Heirs to the Estate of Martin Luther King Jr., c/o Writers House as agent for the proprietor, New York, NY. Copyright © 1962 Martin Luther King Jr. Copyright renewed 1991 Coretta Scott King; (3) Commentary, February 1965; (4) James Farmer, Freedom, When? (New York: Random House, 1965), 25–27, 42–47; (5) Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation (New York: Vintage, 1992, orig. 1967), 37, 44.

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

Question

Compare sources 1 and 3. What does Rustin mean when he says that ending segregation in public accommodations has not affected the “fundamental conditions” of African American life? How does King’s point in document 1 address such issues?

Question

Examine the two photographs. What do they reveal about different kinds of protest? About different perspectives among African Americans?

Question

What does “self-determination” mean for Farmer and Carmichael and Hamilton?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Question

Compose an essay in which you use the documents above, in addition to your reading of the chapter, to explore and explain different approaches to African American rights in the 1960s. In particular, think about how all of the documents come from a single movement, yet each expresses a distinct viewpoint and a distinct way of conceiving what “the struggle” is about. How do these approaches compare to the tactics of earlier struggles for civil rights?