America’s History: Printed Page 896

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 814

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 792

Rise of the Chicano Movement

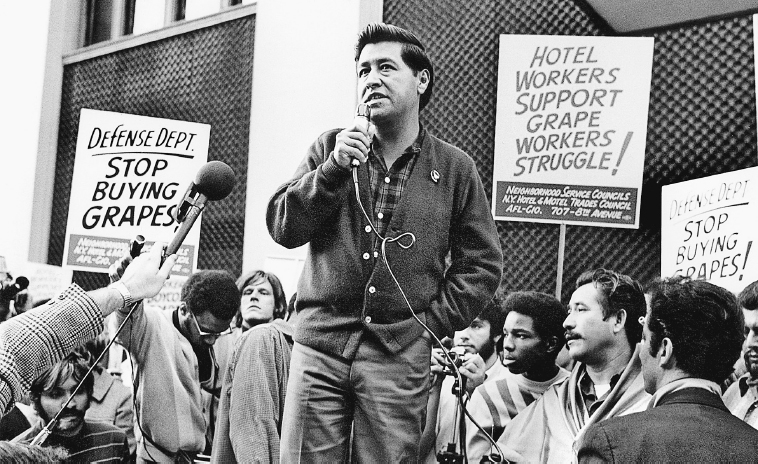

Mexican Americans had something of a counterpart to Martin Luther King: Cesar Chavez. In Chavez’s case, however, economic struggle in community organizations and the labor movement had shaped his approach to mobilizing society’s disadvantaged. He and Dolores Huerta had worked for the Community Service Organization (CSO), a California group founded in the 1950s to promote Mexican political participation and civil rights. Leaving that organization in 1962, Chavez concentrated on the agricultural region around Delano, California. With Huerta, he organized the United Farm Workers (UFW), a union for migrant workers.

Huerta was a brilliant organizer, but the deeply spiritual and ascetic Chavez embodied the moral force behind what was popularly called La Causa. A 1965 grape pickers’ strike led the UFW to call a nationwide boycott of table grapes, bringing Chavez huge publicity and backing from the AFL-CIO. In a bid for attention to the struggle, Chavez staged a hunger strike in 1968, which ended dramatically after twenty-eight days with Senator Robert F. Kennedy at his side to break the fast. Victory came in 1970 when California grape growers signed contracts recognizing the UFW.

Mexican Americans shared some civil rights concerns with African Americans — especially access to jobs — but they also had unique concerns: the status of the Spanish language in schools, for instance, and immigration policy. Mexican Americans had been politically active since the 1940s, aiming to surmount factors that obstructed their political involvement: poverty, language barriers, and discrimination. Their efforts began to pay off in the 1960s, when the Mexican American Political Association (MAPA) mobilized support for John F. Kennedy and worked successfully with other organizations to elect Mexican American candidates such as Edward Roybal of California and Henry González of Texas to Congress. Two other organizations, the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund (MALDF) and the Southwest Voter Registration and Education Project, carried the fight against discrimination to Washington, D.C., and mobilized Mexican Americans into an increasingly powerful voting bloc.

Younger Mexican Americans grew impatient with civil rights groups such as MAPA and MALDF, however. The barrios of Los Angeles and other western cities produced the militant Brown Berets, modeled on the Black Panthers (who wore black berets). Rejecting their elders’ assimilationist approach (that is, a belief in adapting to Anglo society), fifteen hundred Mexican American students met in Denver in 1969 to hammer out a new political and cultural agenda. They proclaimed a new term, Chicano (and its feminine form, Chicana), to replace Mexican American, and later organized a political party, La Raza Unida (The United Race), to promote Chicano interests. Young Chicana feminists formed a number of organizations, including Las Hijas (The Daughters), which organized women both on college campuses and in the barrios. In California and many southwestern states, students staged demonstrations to press for bilingual education, the hiring of more Chicano teachers, and the creation of Chicano studies programs. By the 1970s, dozens of such programs were offered at universities throughout the region.