America’s History: Printed Page 914

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 829

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 809

Rise of the Student Movement

College students, many of them inspired by the civil rights movement, had begun to organize and agitate for social change. In Ann Arbor, Michigan, they founded Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in 1960. Two years later, forty students from Big Ten and Ivy League universities held the first national SDS convention in Port Huron, Michigan. Tom Hayden penned a manifesto, the Port Huron Statement, expressing students’ disillusionment with the nation’s consumer culture and the gulf between rich and poor. “We are people of this generation,” Hayden wrote, “bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit.” These students rejected Cold War foreign policy, including the war in Vietnam.

The New Left The founders of SDS referred to their movement as the New Left to distinguish themselves from the Old Left — communists and socialists of the 1930s and 1940s. As New Left influence spread, it hit major university towns first — places such as Madison, Wisconsin, and Berkeley, California. One of the first major demonstrations erupted in the fall of 1964 at the University of California at Berkeley after administrators banned student political activity on university grounds. In protest, student organizations formed the Free Speech Movement and organized a sit-in at the administration building. Some students had just returned from Freedom Summer in Mississippi, radicalized by their experience. Mario Savio spoke for many when he compared the conflict in Berkeley to the civil rights struggle in the South: “The same rights are at stake in both places — the right to participate as citizens in a democratic society and to struggle against the same enemy.” Emboldened by the Berkeley movement, students across the nation were soon protesting their universities’ academic policies and then, more passionately, the Vietnam War.

One spur to student protest was the military’s Selective Service System, which in 1967 abolished automatic student deferments. To avoid the draft, some young men enlisted in the National Guard or applied for conscientious objector status; others avoided the draft by leaving the country, most often for Canada or Sweden. In public demonstrations, opponents of the war burned their draft cards, picketed induction centers, and on a few occasions broke into Selective Service offices and destroyed records. Antiwar demonstrators numbered in the tens or, at most, hundreds of thousands — a small fraction of American youth — but they were vocal, visible, and determined.

Students were on the front lines as the campaign against the war escalated. The 1967 Mobilization to End the War brought 100,000 protesters into the streets of San Francisco, while more than a quarter million followed Martin Luther King Jr. from Central Park to the United Nations in New York. Another 100,000 marched on the Pentagon. President Johnson absorbed the blows and counterpunched — “The enemy’s hope for victory … is in our division, our weariness, our uncertainty,” he proclaimed — but it had become clear that Johnson’s war, as many began calling it, was no longer uniting the country.

Young Americans for Freedom The New Left was not the only political force on college campuses. Conservative students were less noisy but more numerous. For them, the 1960s was not about protesting the war, staging student strikes, and idolizing Black Power. Inspired by the group Young Americans for Freedom (YAF), conservative students asserted their faith in “God-given free will” and their fear that the federal government “accumulates power which tends to diminish order and liberty.” The YAF, the largest student political organization in the country, defended free enterprise and supported the war in Vietnam. Its founding principles were outlined in “The Sharon Statement,” drafted (in Sharon, Connecticut) two years before the Port Huron Statement, and inspired young conservatives, many of whom would play important roles in the Reagan administration in the 1980s.

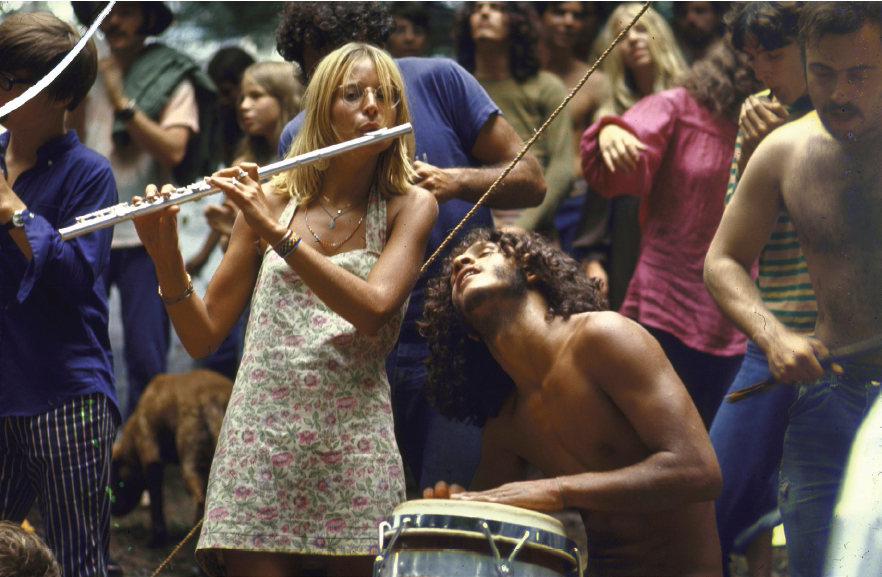

The Counterculture While the New Left organized against the political and economic system and the YAF defended it, many other young Americans embarked on a general revolt against authority and middle-class respectability. The “hippie” — identified by ragged blue jeans or army fatigues, tie-dyed T-shirts, beads, and long unkempt hair — symbolized the new counterculture. With roots in the 1950s Beat culture of New York’s Greenwich Village and San Francisco’s North Beach, the 1960s counterculture initially turned to folk music for its inspiration. Pete Seeger set the tone for the era’s idealism with songs such as the 1961 antiwar ballad “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” In 1963, the year of the civil rights demonstrations in Birmingham and President Kennedy’s assassination, Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” reflected the impatience of people whose faith in America was wearing thin. Joan Baez emerged alongside Dylan and pioneered a folk sound that inspired a generation of female musicians.

By the mid-1960s, other winds of change in popular music came from the Beatles, four working-class Brits whose awe-inspiring music — by turns lyrical and driving — spawned a commercial and cultural phenomenon known as Beatlemania. American youths’ embrace of the Beatles — as well as even more rebellious bands such as the Rolling Stones, the Who, and the Doors — deepened the generational divide between young people and their elders. So did the recreational use of drugs — especially marijuana and the hallucinogen popularly known as LSD or acid — which was celebrated in popular music in the second half of the 1960s.

For a brief time, adherents of the counterculture believed that a new age was dawning. In 1967, the “world’s first Human Be-In” drew 20,000 people to Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. That summer — called the Summer of Love — San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury, New York’s East Village, Chicago’s Uptown neighborhoods, and the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles swelled with young dropouts, drifters, and teenage runaways whom the media dubbed “flower children.” Although most young people had little interest in all-out revolt, media coverage made it seem as though all of American youth was rejecting the nation’s social and cultural norms.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

Contrast the political views of the SDS, the YAF, and the counterculture. How would you explain the differences?