America’s History: Printed Page 919

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 833

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 812

War Abroad, Tragedy at Home

President Johnson had gambled in 1965 on a quick victory in Vietnam, before the political cost of escalation came due. But there was no quick victory. North Vietnamese and Vietcong forces fought on, the South Vietnamese government repeatedly collapsed, and American casualties mounted. By early 1968, the death rate of U.S. troops had reached several hundred a week. Johnson and his generals kept insisting that there was “light at the end of the tunnel.” Facts on the ground showed otherwise.

The Tet Offensive On January 30, 1968, the Vietcong unleashed a massive, well-coordinated assault in South Vietnam. Timed to coincide with Tet, the Vietnamese new year, the offensive struck thirty-six provincial capitals and five of the six major cities, including Saigon, where the Vietcong nearly overran the U.S. embassy. In strictly military terms, the Tet offensive was a failure, with very heavy Vietcong losses. But psychologically, the effect was devastating. Television brought into American homes shocking live images: the American embassy under siege and the Saigon police chief placing a pistol to the head of a Vietcong suspect and executing him.

The Tet offensive made a mockery of official pronouncements that the United States was winning the war. How could an enemy on the run manage such a large-scale, complex, and coordinated attack? Just before Tet, a Gallup poll found that 56 percent of Americans considered themselves “hawks” (supporters of the war), while only 28 percent identified with the “doves” (war opponents). Three months later, doves outnumbered hawks 42 to 41 percent. Without embracing the peace movement, many Americans simply concluded that the war was unwinnable.

The Tet offensive undermined Johnson and discredited his war policies. When the 1968 presidential primary season got under way in March, antiwar senators Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota and Robert Kennedy of New York, JFK’s brother, challenged Johnson for the Democratic nomination. Discouraged, perhaps even physically exhausted, on March 31 Johnson stunned the nation by announcing that he would not seek reelection.

Political Assassinations Americans had barely adjusted to the news that a sitting president would not stand for reelection when, on April 4, James Earl Ray shot and killed Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis. Riots erupted in more than a hundred cities. The worst of them, in Baltimore, Chicago, and Washington, D.C., left dozens dead and hundreds of millions of dollars in property damaged or destroyed. The violence on the streets of Saigon had found an eerie parallel on the streets of the United States.

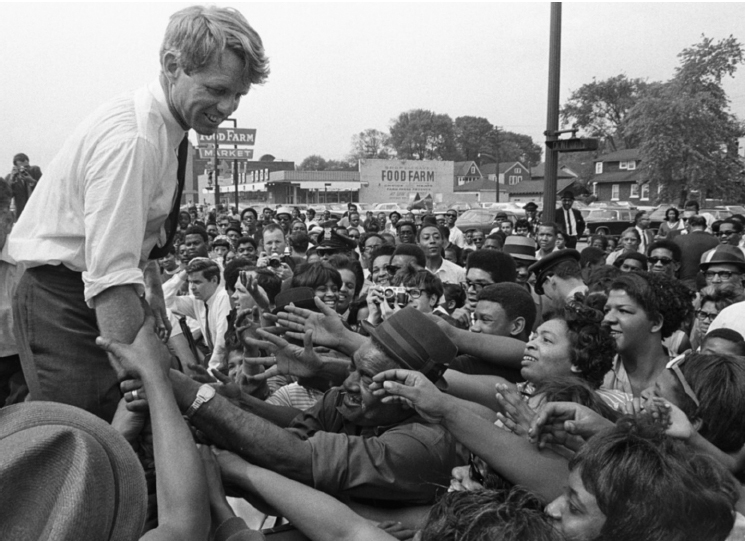

One city that did not erupt was Indianapolis. There, Robert Kennedy, in town campaigning in the Indiana primary, gave a quiet, somber speech to the black community on the night of King’s assassination. Americans could continue to move toward “greater polarization,” Kennedy said, “black people amongst blacks, white amongst whites,” or “we can replace that violence … with an effort to understand, compassion and love.” Kennedy sympathized with African Americans’ outrage at whites, but he begged them not to strike back in retribution. Impromptu and heartfelt, Kennedy’s speech was a plea to follow King’s nonviolent example, even as the nation descended into greater violence.

But two months later, having emerged as the front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination, Kennedy, too, would be gone. On June 5, as he was celebrating his victory in the California primary over Eugene McCarthy, Kennedy was shot dead by a young Palestinian named Sirhan Sirhan. Amid the national mourning for yet another political murder, one newspaper columnist declared that “the country does not work anymore.” Newsweek asked, “Has violence become a way of life?” Kennedy’s assassination was a calamity for the Democratic Party because only he had seemed able to surmount the party’s fissures over Vietnam. In the space of eight weeks, American liberals had lost two of their most important national figures, King and Kennedy. A third, Johnson, was unpopular and politically damaged. Without these unifying leaders, the crisis of liberalism had become unmanageable.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

What changed between 1965 and 1968, and how did these developments affect national political life? (See also “The Antiwar Movement and the 1968 Election.”)