America’s History: Printed Page 924

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 838

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 816

Women’s Liberation

Among women, 1968 also marked a break with the past. The late 1960s spawned a new brand of feminism: women’s liberation. These feminists were primarily younger, college-educated women fresh from the New Left, antiwar, and civil rights movements. Those movements’ male leaders, they discovered, considered women little more than pretty helpers who typed memos and fetched coffee. Women who tried to raise feminist issues at civil rights and antiwar events were shouted off the platform with jeers such as “Move on, little girl, we have more important issues to talk about here than women’s liberation.”

Fed up with second-class status, and well versed in the tactics of organization and protest, women radicals broke away and organized on their own. Unlike the National Organization for Women (NOW), the women’s liberation movement was loosely structured, comprising an alliance of collectives in New York, San Francisco, Boston, and other big cities and college towns. “Women’s lib,” as it was dubbed by a skeptical media, went public in 1968 at the Miss America pageant. Demonstrators carried posters of women’s bodies labeled as slabs of beef — implying that society treated them as meat. Mirroring the identity politics of Black Power activists and the self-dramatization of the counterculture, women’s liberation sought an end to the denigration and exploitation of women. “Sisterhood is powerful!” read one women’s liberationist manifesto. The national Women’s Strike for Equality in August 1970 brought hundreds of thousands of women into the streets of the nation’s cities for marches and demonstrations.

By that year, new terms such as sexism and male chauvinism had become part of the national vocabulary. As converts flooded in, the two branches of the women’s movement began to converge. Radical women realized that key feminist goals — child care, equal pay, and reproduction rights — could best be achieved in the political arena. At the same time, more traditional activists, exemplified by Betty Friedan, developed a broader view of women’s oppression. They came to understand that women required more than equal opportunity: the culture that regarded women as nothing more than sexual objects and helpmates to men had to change as well. Although still largely white and middle class, feminists began to think of themselves as part of a broad social crusade.

“Sisterhood” did not unite all women, however. Rather than joining white-led women’s liberation organizations, African American and Latina women continued to work within the larger framework of the civil rights movement. New groups such as the Combahee River Collective and the National Black Feminist Organization arose to speak for the concerns of African American women. They criticized sexism but were reluctant to break completely with black men and the struggle for racial equality. Chicana feminists came from Catholic backgrounds in which motherhood and family were held in high regard. “We want to walk hand in hand with the Chicano brothers, with our children, our viejitos [elders], our Familia de la Raza,” one Chicana feminist wrote. Black and Chicana feminists embraced the larger movement for women’s rights but carried on their own struggles to address specific needs in their communities.

One of the most important contributions of women’s liberation was to raise awareness about what feminist Kate Millett called sexual politics. Liberationists argued that unless women had control over their own bodies, they could not freely shape their destinies. They campaigned for reproductive rights, especially access to abortion, and railed against a culture that blamed women in cases of sexual assault and turned a blind eye to sexual harassment in the workplace.

Meanwhile, women’s opportunities expanded dramatically in higher education. Dozens of formerly all-male bastions such as Yale, Princeton, and the U.S. military academies admitted women undergraduates for the first time. Colleges started women’s studies programs, which eventually numbered in the hundreds, and the proportion of women attending graduate and professional schools rose markedly. With the adoption of Title IX in 1972, Congress broadened the 1964 Civil Rights Act to include educational institutions, prohibiting colleges and universities that received federal funds from discriminating on the basis of sex. By requiring comparable funding for sports programs, Title IX made women’s athletics a real presence on college campuses.

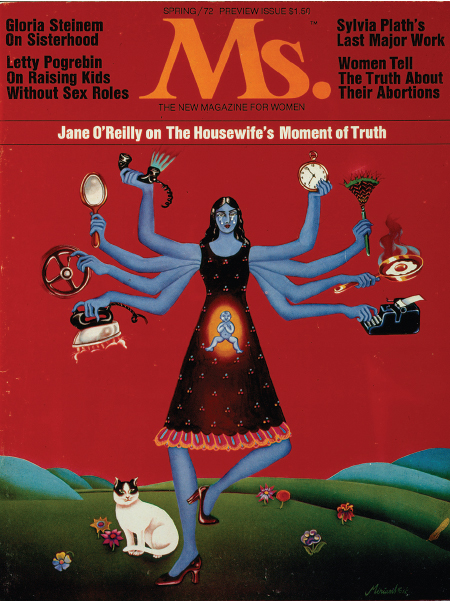

Women also became increasingly visible in public life. Congresswomen Bella Abzug and Shirley Chisholm joined Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem, the founder of Ms. magazine, to create the National Women’s Political Caucus in 1971. Abzug and Chisholm, both from New York, joined Congresswomen Patsy Mink from Hawaii and Martha Griffiths from Michigan to sponsor equal rights legislation. Congress authorized child-care tax deductions for working parents in 1972 and in 1974 passed the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which enabled married women to get credit, including credit cards and mortgages, in their own names.

Antiwar activists, black and Chicano nationalists, and women’s liberationists had each challenged the Cold War liberalism of the Democratic Party. In doing so, they helped build on the “rights liberalism” forged first by the African American-led civil rights movement. But they also created rifts among competing parts of the former liberal consensus. Many Catholics, for instance, opposed abortion rights and other freedoms sought by women’s liberationists. Still other Democrats, many of them blue-collar trade unionists, believed that antiwar protesters were unpatriotic and that supporting one’s government in time of war was a citizen’s duty. The antiwar movement and the evolving rights liberalism of the sixties had made the old Democratic coalition increasingly unworkable.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

How did women’s liberation after 1968 differ from the women’s movement of the early 1960s?