America’s History: Printed Page 952

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 864

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 842

The Women’s Movement and Gay Rights

Unlike the civil rights movement, whose signal achievements came in the 1960s, the women’s and gay rights movements flourished in the 1970s. With three influential wings — radical, liberal, and “Third World” — the women’s movement inspired both grassroots activism and legislative action across the nation. For their part, gay activists had further to go: they needed to convince Americans that same-sex relationships were natural and that gay men and lesbians deserved the same protection of the law as all other citizens. Neither movement achieved all of its aims in this era, but each laid a strong foundation for the future.

Women’s Activism In the first half of the 1970s, the women’s liberation movement reached its historic peak. Taking a dizzying array of forms — from lobbying legislatures to marching in the streets and establishing all-female collectives — women’s liberation produced activism on the scale of the earlier black-led civil rights movement. Women’s centers, as well as women-run child-care facilities, began to spring up in cities and towns. A feminist art and poetry movement flourished. Women challenged the admissions policies of all-male colleges and universities — opening such prestigious universities as Yale and Columbia and nearly bringing an end to male-only institutions of higher education. Female scholars began to transform higher education: by studying women’s history, by increasing the number of women on college and university faculties, and by founding women’s studies programs.

Much of women’s liberation activism focused on the female body. Inspired by the Boston collective that first published Our Bodies, Ourselves — a groundbreaking book on women’s health — the women’s health movement founded dozens of medical clinics, encouraged women to become physicians, and educated millions of women about their bodies. To reform antiabortion laws, activists pushed for remedies in more than thirty state legislatures. Women’s liberationists founded the antirape movement, established rape crisis centers around the nation, and lobbied state legislatures and Congress to reform rape laws. Many of these endeavors and movements began as shoestring operations in living rooms and kitchens: Our Bodies, Ourselves was first published as a 35-cent mimeographed booklet, and the antirape movement began in small consciousness-raising groups that met in churches and community centers. By the end of the decade, however, all of these causes had national organizations and touched the lives of millions of American women.

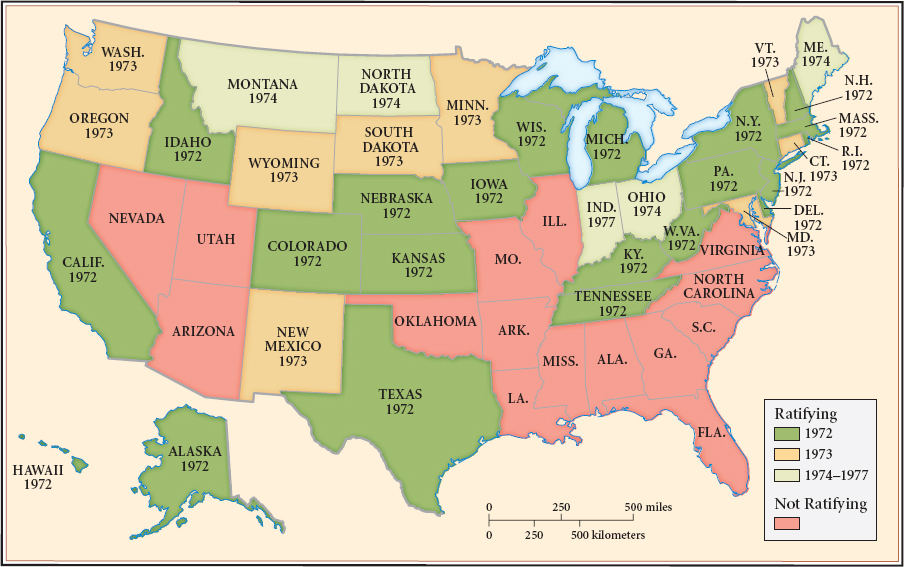

Equal Rights Amendment Buoyed by this flourishing of activism, the women’s movement renewed the fight for an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the Constitution. First introduced in 1923, the ERA stated, in its entirety, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State on the basis of sex.” Vocal congressional women, such as Patsy Mink (Democrat, Hawaii), Bella Abzug (Democrat, New York), and Shirley Chisholm (Democrat, New York), found enthusiastic male allies — among both Democrats and Republicans — and Congress adopted the amendment in 1972. Within just two years, thirty-four of the necessary thirty-eight states had ratified it, and the ERA appeared headed for adoption. But then, progress abruptly halted (Map 29.2).

Credit for putting the brakes on ERA ratification goes chiefly to a remarkable woman: Phyllis Schlafly, a lawyer long active in conservative causes. Despite her own flourishing career, Schlafly advocated traditional roles for women. The ERA, she proclaimed, would create an unnatural “unisex society,” with women drafted into the army and forced to use single-sex toilets. Abortion, she alleged, could never be prohibited by law. Led by Schlafly’s organization, STOP ERA (founded in 1972), thousands of women mobilized, showing up at statehouses with home-baked bread and apple pies. As labels on baked goods at one anti-ERA rally expressed it: “My heart and hand went into this dough / For the sake of the family please vote no.” It was a message that resonated widely, especially among those troubled by the rapid pace of social change (American Voices). The ERA never was ratified, despite a congressional extension of the deadline to June 30, 1982.

Roe v. Wade In addition to the ERA, the women’s movement had identified another major goal: winning reproductive rights. Activists pursued two tracks: legislative and judicial. In the early 1960s, abortion was illegal in virtually every state. A decade later, thanks to intensive lobbying by women’s organizations, liberal ministers, and physicians, a handful of states, such as New York, Hawaii, California, and Colorado, adopted laws making legal abortions easier to obtain. But progress after that was slow, and women’s advocates turned to the courts. There was reason to be optimistic. The Supreme Court had first addressed reproductive rights in a 1965 case, Griswold v. Connecticut. Griswold struck down an 1879 state law prohibiting the possession of contraception as a violation of married couples’ constitutional “right of privacy.” Following the logic articulated in Griswold, the Court gradually expanded the right of privacy in a series of cases in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Those cases culminated in Roe v. Wade (1973). In that landmark decision, the justices nullified a Texas law that prohibited abortion under any circumstances, even when the woman’s health was at risk, and laid out a new national standard: Abortions performed during the first trimester were protected by the right of privacy. At the time and afterward, some legal authorities questioned whether the Constitution recognized any such privacy right and criticized the Court’s seemingly arbitrary first-trimester timeline. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court chose to move forward, transforming a traditionally state-regulated policy into a national, constitutionally protected right.

For the women’s movement, Roe v. Wade represented a triumph. For evangelical and fundamentalist Christians, Catholics, and conservatives generally, it was a bitter pill. In their view, abortion was, unequivocally, the taking of a human life. These Americans, represented by groups such as the National Right to Life Committee, did not believe that something they regarded as immoral and sinful could be the basis for women’s equality. Women’s advocates responded that illegal abortions — common prior to Roe — were often unsafe procedures, which resulted in physical harm to women and even death. Roe polarized what was already a sharply divided public and mobilized conservatives to seek a Supreme Court reversal or, short of that, to pursue legislation that would strictly limit the conditions under which abortions could be performed. In 1976, they convinced Congress to deny Medicaid funds for abortions, an opening round in a campaign against Roe v. Wade that continues today.

Harvey Milk The gay rights movement had achieved notable victories as well. These, too, proved controversial. More than a dozen cities had passed gay rights ordinances by the mid-1970s, protecting gay men and lesbians from employment and housing discrimination. One such ordinance in Dade County (Miami), Florida, sparked a protest led by Anita Bryant, a conservative Baptist and a television celebrity. Her “Save Our Children” campaign in 1977, which garnered national media attention, resulted in the repeal of the ordinance and symbolized the emergence of a conservative religious movement opposed to gay rights.

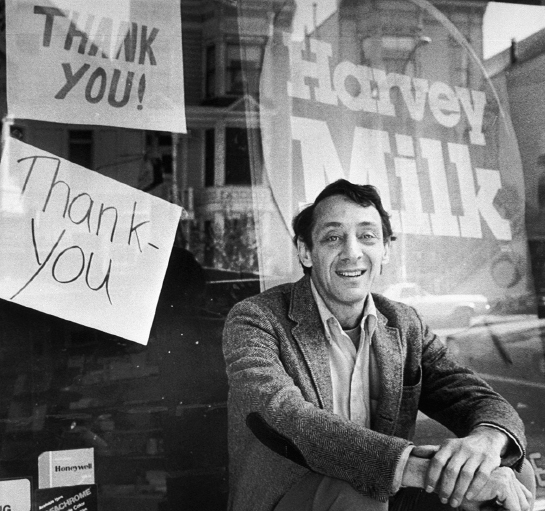

Across the country from Miami, developments in San Francisco looked promising for gay rights advocates, then turned tragic. No one embodied the combination of gay liberation and hard-nosed politics better than a San Francisco camera-shop owner named Harvey Milk. A closeted businessman in New York until he was forty, Milk arrived in San Francisco in 1972 and threw himself into city politics. Fiercely independent, he ran as an openly gay candidate for city supervisor (city council) twice and the state assembly once, both times unsuccessfully.

By mobilizing the “gay vote” into a powerful bloc, Milk finally won a supervisor seat in 1977. He was not the first openly gay elected official in the country — Kathy Kozachenko of Michigan and Elaine Noble of Massachusetts share that distinction — but he became a national symbol of emerging gay political power. Tragically, after he helped to win passage of a gay rights ordinance in San Francisco, he was assassinated in 1978 — along with the city’s mayor, George Moscone — by a disgruntled former supervisor named Dan White. When White was convicted of manslaughter rather than murder, five thousand gays and lesbians in San Francisco marched on city hall.

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES

Question

How did the idea of civil rights expand during the 1970s?