America’s History: Printed Page 942

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 853

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 832

Economic Transformation

In addition to the energy crisis, the economy was beset by a host of longer-term problems. Government spending on the Vietnam War and the Great Society made for a growing federal deficit and spiraling inflation. In the industrial sector, the country faced more robust competition from West Germany and Japan. America’s share of world trade dropped from 32 percent in 1955 to 18 percent in 1970 and was headed downward. As a result, in a blow to national pride, nine Western European countries had surpassed the United States in per capita gross domestic product (GDP) by 1980.

Many of these economic woes highlighted a broader, multigenerational transformation in the United States: from an industrial-manufacturing economy to a postindustrial-service one. That transformation, which continues to this day, meant that the United States began to produce fewer automobiles, appliances, and televisions and more financial services, health-care services, and management consulting services — not to mention many millions of low-paying jobs in the restaurant, retail, and tourist industries.

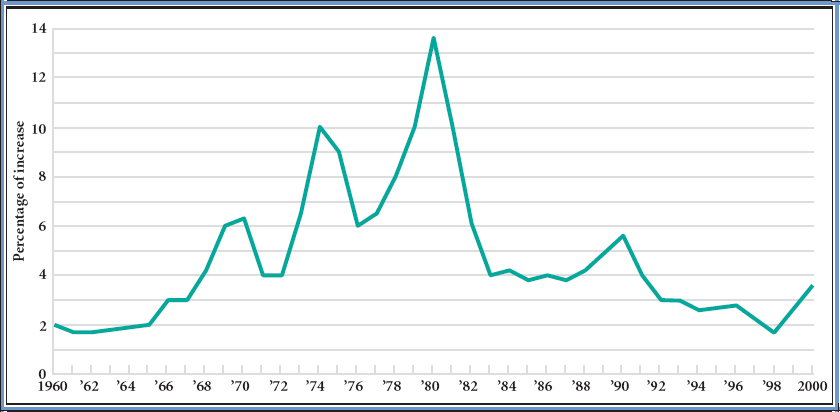

In the 1970s, the U.S. economy was hit simultaneously by unemployment, stagnant consumer demand, and inflation — a combination called stagflation — which contradicted a basic principle taught by economists: prices were not supposed to rise in a stagnant economy (Figure 29.2). For ordinary Americans, stagflation meant a noticeable decline in purchasing power, as discretionary income per worker dropped 18 percent between 1973 and 1982. None of the three presidents of the decade — Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter — had much luck tackling stagflation. Nixon’s New Economic Policy was perhaps the most radical attempt. Nixon imposed temporary price and wage controls in 1971 in an effort to curb inflation. Then he took an even bolder step: removing the United States from the gold standard, which allowed the dollar to float in international currency markets and effectively ended the Bretton Woods monetary system established after World War II.

The underlying weaknesses in the U.S. economy remained, however. Ford, too, had little success. His Whip Inflation Now (WIN) campaign urged Americans to cut food waste and do more with less, a noble but deeply unpopular idea among the American public. Carter’s policies, considered in a subsequent section of this chapter, were similarly ineffective. The fruitless search for a new economic order was a hallmark of 1970s politics.

Deindustrialization America’s economic woes struck hardest at the industrial sector, which suddenly — shockingly — began to be dismantled. Worst hit was the steel industry, which for seventy-five years had been the economy’s crown jewel. Unscathed by World War II, U.S. steel producers had enjoyed an open, hugely profitable market. But lack of serious competition left them without incentives to replace outdated plants and equipment. When West Germany and Japan rebuilt their steel industries, these facilities incorporated the latest technology. Foreign steel flooded into the United States during the 1970s, and the American industry was simply overwhelmed. Formerly titanic steel companies began a massive dismantling; virtually the entire Pittsburgh region, once a national hub of steel production, lost its heavy industry in a single generation. By the mid-1980s, downsizing, automation, and investment in new technologies made the American steel industry competitive again — but it was a shadow of its former self, and it continues to struggle to this day.

The steel industry was the prime example of what became known as deindustrialization. The country was in the throes of an economic transformation that left it largely stripped of its industrial base. Steel was hardly alone. A swath of the Northeast and Midwest, the country’s manufacturing heartland, became the nation’s Rust Belt (Map 29.1), strewn with abandoned plants and distressed communities. The automobile, tire, textile, and other consumer durable industries (appliances, electronics, furniture, and the like) all started shrinking in the 1970s. In 1980, Business Week bemoaned “plant closings across the continent” and called for the “reindustrialization of America.”

Organized Labor in Decline Deindustrialization threw many tens of thousands of blue-collar workers out of well-paid union jobs. One study followed 4,100 steelworkers left jobless by the 1977 shutdown of the Campbell Works of the Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. Two years later, 35 percent had retired early at half pay; 10 percent had moved; 15 percent were still jobless, with unemployment benefits long gone; and 40 percent had found local work, but mostly in low-paying, service-sector jobs. In another instance, between 1978 and 1981, eight Los Angeles companies — including such giants as Ford, Uniroyal, and U.S. Steel — closed factories employing 18,000 workers. These Ohio and California workers, like hundreds of thousands of their counterparts across the nation, had fallen from their perch in the middle class (America Compared).

Deindustrialization dealt an especially harsh blow to the labor movement, which had facilitated the postwar expansion of that middle class. In the early 1970s, as inflation hit, the number of strikes surged; 2.4 million workers participated in work stoppages in 1970 alone. However, industry argued that it could no longer afford union demands, and labor’s bargaining power produced fewer and fewer concrete results. In these hard years, the much-vaunted labor-management accord of the 1950s, which raised profits and wages by passing costs on to consumers, went bust. Instead of seeking higher wages, unions now mainly fought to save jobs. Union membership went into steep decline, and by the mid-1980s organized labor represented less than 18 percent of American workers, the lowest level since the 1920s. The impact on liberal politics was huge. With labor’s decline, a main buttress of the New Deal coalition was coming undone.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

What major developments shaped the American economy in the 1970s and contributed to its transformation?