America’s History: Printed Page 60

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 51

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 50

New England

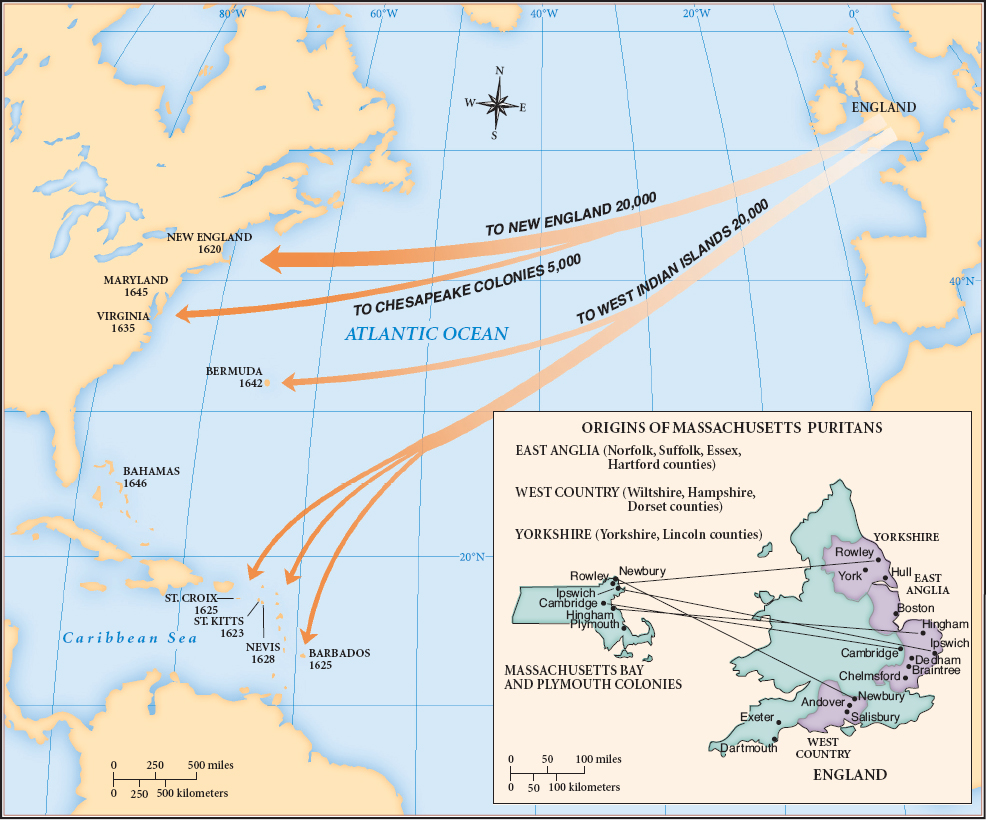

In 1620, 102 English Protestants landed at a place they called Plymouth, near Cape Cod. A decade later, a much larger group began to arrive just north of Plymouth, in the newly chartered Massachusetts Bay Colony. By 1640, the region had attracted more than 20,000 migrants (Map 2.6). Unlike the early arrivals in Virginia and Barbados, these were not parties of young male adventurers seeking their fortunes or bound to labor for someone else. They came in family groups to create communities like the ones they left behind, except that they intended to establish them according to Protestant principles, as John Calvin had done in Geneva. Their numbers were small compared to the Caribbean and the Chesapeake, but their balanced sex ratio and organized approach to community formation allowed them to multiply quickly. By distributing land broadly, they built a society of independent farm families. And by establishing a “holy commonwealth,” they gave a moral dimension to American history that survives today.

The Pilgrims The Pilgrims were religious separatists — Puritans who had left the Church of England. When King James I threatened to drive Puritans “out of the land, or else do worse,” some Puritans chose to live among Dutch Calvinists in Holland. Subsequently, 35 of these exiles resolved to maintain their English identity by moving to America. Led by William Bradford and joined by 67 migrants from England, the Pilgrims sailed to America aboard the Mayflower. Because they lacked a royal charter, they combined themselves “together into a civill body politick,” as their leader explained. This Mayflower Compact used the Puritans’ self-governing religious congregation as the model for their political structure.

Only half of the first migrant group survived until spring, but thereafter Plymouth thrived; the cold climate inhibited the spread of mosquito-borne disease, and the Pilgrims’ religious discipline encouraged a strong work ethic. Moreover, a smallpox epidemic in 1618 devastated the local Wampanoags, minimizing the danger they posed. By 1640, there were 3,000 settlers in Plymouth. To ensure political stability, they established representative self-government, broad political rights, property ownership, and religious freedom of conscience.

Meanwhile, England plunged deeper into religious turmoil. When King Charles I repudiated certain Protestant doctrines, including the role of grace in salvation, English Puritans, now powerful in Parliament, accused the king of “popery” — of holding Catholic beliefs. In 1629, Charles dissolved Parliament, claimed the authority to rule by “divine right,” and raised money through royal edicts and the sale of monopolies. When Charles’s Archbishop William Laud began to purge dissident ministers, thousands of Puritans — Protestants who did not separate from the Church of England but hoped to purify it of its ceremony and hierarchy — fled to America.

John Winthrop and Massachusetts Bay The Puritan exodus began in 1630 with the departure of 900 migrants led by John Winthrop, a well-educated country squire who became the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Calling England morally corrupt and “overburdened with people,” Winthrop sought land for his children and a place in Christian history for his people. “We must consider that we shall be as a City upon a Hill,” Winthrop told the migrants. “The eyes of all people are upon us.” Like the Pilgrims, the Puritans envisioned a reformed Christian society with “authority in magistrates, liberty in people, purity in the church,” as minister John Cotton put it. By their example, they hoped to inspire religious reform throughout Christendom.

|

To see a longer excerpt of Winthrop’s “City Upon a Hill” sermon, along with other primary sources from this period, see Sources for America’s History. |

Winthrop and his associates governed the Massachusetts Bay Colony from the town of Boston. They transformed their joint-stock corporation — a commercial agreement that allows investors to pool their resources — into a representative political system with a governor, council, and assembly. To ensure rule by the godly, the Puritans limited the right to vote and hold office to men who were church members. Rejecting the Plymouth Colony’s policy of religious tolerance, the Massachusetts Bay Colony established Puritanism as the state-supported religion, barred other faiths from conducting services, and used the Bible as a legal guide. “Where there is no Law,” they said, magistrates should rule “as near the law of God as they can.” Over the next decade, about 10,000 Puritans migrated to the colony, along with 10,000 others fleeing hard times in England.

The New England Puritans sought to emulate the simplicity of the first Christians. Seeing bishops as “traitours unto God,” they placed power in the congregation of members — hence the name Congregationalist for their churches. Inspired by John Calvin, many Puritans embraced predestination, the idea that God saved only a few chosen people. Church members often lived in great anxiety, worried that God had not placed them among the “elect.” Some hoped for a conversion experience, the intense sensation of receiving God’s grace and being “born again.” Other Puritans relied on “preparation,” the confidence in salvation that came from spiritual guidance by their ministers. Still others believed that they were God’s chosen people, the new Israelites, and would be saved if they obeyed his laws.

Roger Williams and Rhode Island To maintain God’s favor, the Massachusetts Bay magistrates purged their society of religious dissidents. One target was Roger Williams, the Puritan minister in Salem, a coastal town north of Boston. Williams opposed the decision to establish an official religion and praised the Pilgrims’ separation of church and state. He advocated toleration, arguing that political magistrates had authority over only the “bodies, goods, and outward estates of men,” not their spiritual lives. Williams also questioned the Puritans’ seizure of Indian lands. The magistrates banished him from the colony in 1636.

Williams and his followers settled 50 miles south of Boston, founding the town of Providence on land purchased from the Narragansett Indians. Other religious dissidents settled nearby at Portsmouth and Newport. In 1644, these settlers obtained a corporate charter from Parliament for a new colony — Rhode Island — with full authority to rule themselves. In Rhode Island, as in Plymouth, there was no legally established church, and individuals could worship God as they pleased.

Anne Hutchinson The Massachusetts Bay magistrates saw a second threat to their authority in Anne Hutchinson. The wife of a merchant and mother of seven, Hutchinson held weekly prayer meetings for women and accused various Boston clergymen of placing undue emphasis on good behavior. Like Martin Luther, Hutchinson denied that salvation could be earned through good deeds. There was no “covenant of works” that would save the well-behaved; only a “covenant of grace” through which God saved those he predestined for salvation. Hutchinson likewise declared that God “revealed” divine truth directly to individual believers, a controversial doctrine that the Puritan magistrates denounced as heretical.

The magistrates also resented Hutchinson because of her sex. Like other Christians, Puritans believed that both men and women could be saved. But gender equality stopped there. Women were inferior to men in earthly affairs, said leading Puritan divines, who told married women: “Thy desires shall bee subject to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee.” Puritan women could not be ministers or lay preachers, nor could they vote in church affairs. In 1637, the magistrates accused Hutchinson of teaching that inward grace freed an individual from the rules of the Church and found her guilty of holding heretical views. Banished, she followed Roger Williams into exile in Rhode Island.

Other Puritan groups moved out from Massachusetts Bay in the 1630s and settled on or near the Connecticut River. For several decades, the colonies of Connecticut, New Haven, and Saybrook were independent of one another; in 1660, they secured a charter from King Charles II (r. 1660–1685) for the self-governing colony of Connecticut. Like Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut had a legally established church and an elected governor and assembly; however, it granted voting rights to most property-owning men, not just to church members as in the original Puritan colony.

The Puritan Revolution in England Meanwhile, a religious civil war engulfed England. Archbishop Laud had imposed the Church of England prayer book on Presbyterian Scotland in 1637; five years later, a rebel Scottish army invaded England. Thousands of English Puritans (and hundreds of American Puritans) joined the Scots, demanding religious reform and parliamentary power. After years of civil war, parliamentary forces led by Oliver Cromwell emerged victorious. In 1649, Parliament beheaded King Charles I, proclaimed a republican Commonwealth, and banished bishops and elaborate rituals from the Church of England.

The Puritan triumph in England was short-lived. Popular support for the Commonwealth ebbed after Cromwell took dictatorial control in 1653. Following his death in 1658, moderate Protestants and a resurgent aristocracy restored the monarchy and the hierarchy of bishops. With Charles II (r. 1660–1685) on the throne, England’s experiment in radical Protestant government came to an end.

For the Puritans in America, the restoration of the monarchy began a new phase of their “errand into the wilderness.” They had come to New England expecting to return to Europe in triumph. When the failure of the English Revolution dashed that sacred mission, ministers exhorted congregations to create a godly republican society in America. The Puritan colonies now stood as outposts of Calvinism and the Atlantic republican tradition.

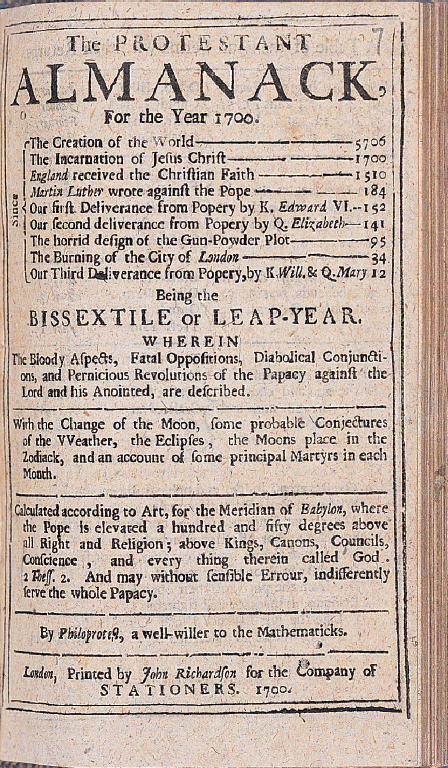

Puritanism and Witchcraft Like Native Americans, Puritans believed that the physical world was full of supernatural forces. Devout Christians saw signs of God’s (or Satan’s) power in blazing stars, birth defects, and other unusual events. Noting after a storm that the houses of many ministers “had been smitten with Lightning,” Cotton Mather, a prominent Puritan theologian, wondered “what the meaning of God should be in it.”

Puritans were hostile toward people who they believed tried to manipulate these forces, and many were willing to condemn neighbors as Satan’s “wizards” or “witches.” People in the town of Andover “were much addicted to sorcery,” claimed one observer, and “there were forty men in it that could raise the Devil as well as any astrologer.” Between 1647 and 1662, civil authorities in New England hanged fourteen people for witchcraft, most of them older women accused of being “double-tongued” or of having “an unruly spirit.”

The most dramatic episode of witch-hunting occurred in Salem in 1692. Several girls who had experienced strange seizures accused neighbors of bewitching them. When judges at the accused witches’ trials allowed the use of “spectral” evidence — visions of evil beings and marks seen only by the girls — the accusations spun out of control. Eventually, Massachusetts Bay authorities tried 175 people for witchcraft and executed 19 of them. The causes of this mass hysteria were complex and are still debated. Some historians point to group rivalries: many accusers were the daughters or servants of poor farmers, whereas many of the alleged witches were wealthier church members or their friends. Because 18 of those put to death were women, other historians see the episode as part of a broader Puritan effort to subordinate women. Still others focus on political instability in Massachusetts Bay in the early 1690s and on fears raised by recent Indian attacks in nearby Maine, which had killed the parents of some of the young accusers. It is likely that all of these causes played some role in the executions.

Whatever the cause, the Salem episode marked a major turning point. Shaken by the number of deaths, government officials now discouraged legal prosecutions for witchcraft. Moreover, many influential people embraced the outlook of the European Enlightenment, a major intellectual movement that began around 1675 and promoted a rational, scientific view of the world. Increasingly, educated men and women explained strange happenings and sudden deaths by reference to “natural causes,” not witchcraft. Unlike Cotton Mather (1663–1728), who believed that lightning was a supernatural sign, Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) and other well-read men of his generation would investigate it as a natural phenomenon.

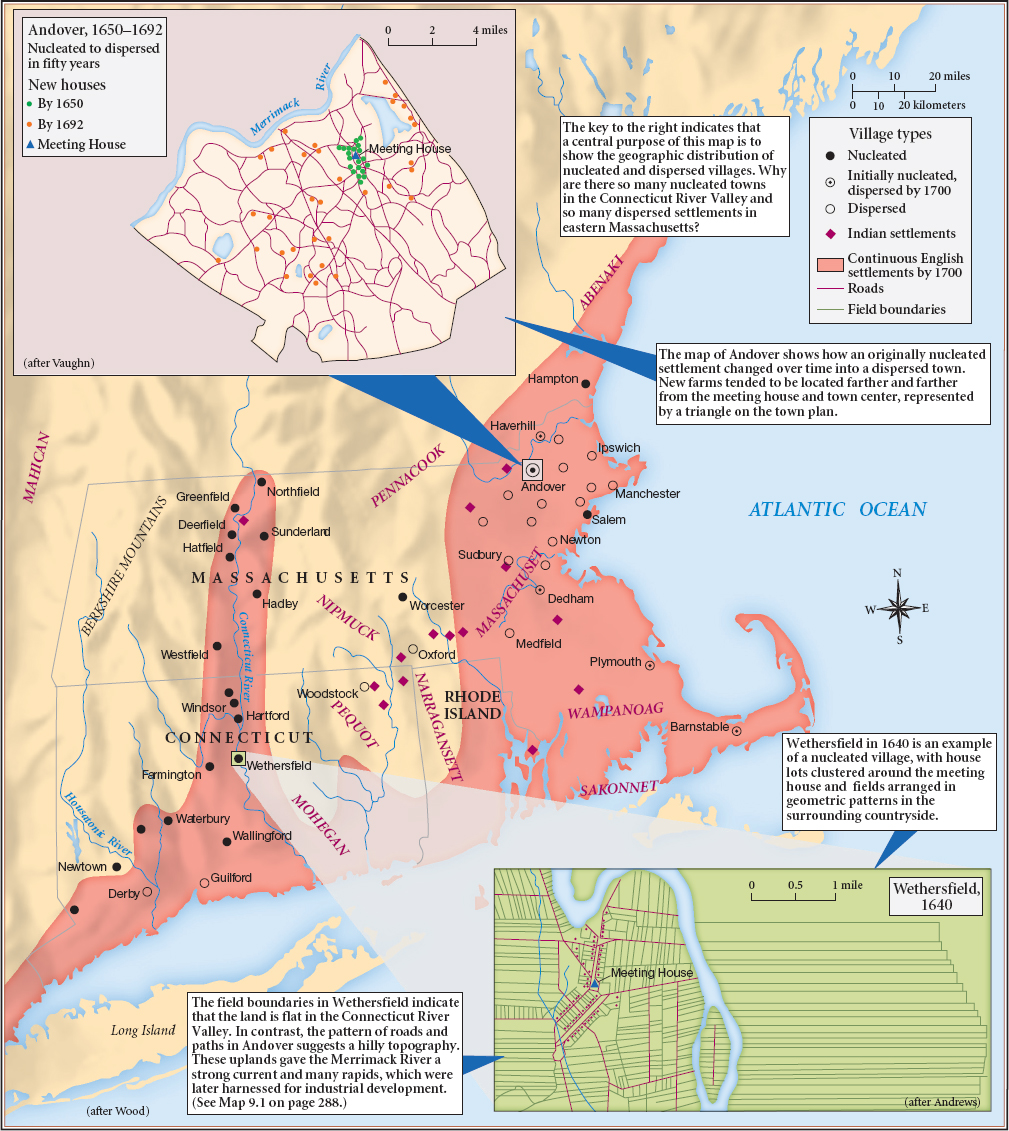

A Yeoman Society, 1630–1700 In building their communities, New England Puritans consciously rejected the feudal practices of English society. Many Puritans came from middling families in East Anglia, a region of pasture lands and few manors, and had no desire to live as tenants of wealthy aristocrats or submit to oppressive taxation by a distant government. They had “escaped out of the pollutions of the world,” the settlers of Watertown in Massachusetts Bay declared, and vowed to live “close togither” in self-governing communities. Accordingly, the General Courts of Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut bestowed land on groups of settlers, who then distributed it among the male heads of families.

Widespread ownership of land did not mean equality of wealth or status. “God had Ordained different degrees and orders of men,” proclaimed Boston merchant John Saffin, “some to be Masters and Commanders, others to be Subjects, and to be commanded.” Town proprietors normally awarded the largest plots to men of high social status who often became selectmen and justices of the peace. However, all families received some land, and most adult men had a vote in the town meeting, the main institution of local government (Map 2.7).

In this society of independent households and self-governing communities, ordinary farmers had much more political power than Chesapeake yeomen and European peasants did. Although Nathaniel Fish was one of the poorest men in the town of Barnstable — he owned just a two-room cottage, 8 acres of land, an ox, and a cow — he was a voting member of the town meeting. Each year, Fish and other Barnstable farmers levied taxes; enacted ordinances governing fencing, roadbuilding, and the use of common fields; and chose the selectmen who managed town affairs. The farmers also selected the town’s representatives to the General Court, which gradually displaced the governor as the center of political authority. For Fish and thousands of other ordinary settlers, New England had proved to be a new world of opportunity.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

What made New England different from New France and New Netherland?