America’s History: Printed Page 66

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 57

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 55

New England’s Indian Wars

Relations between colonists and Indians in early New England were bewilderingly complex. Many rival Indian groups lived there before Europeans arrived; by the 1630s, these groups were bordered by the Dutch colony of New Netherland to their west and the various English settlements to the east: Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Haven, and Saybrook. The region’s Indian leaders created various alliances for the purposes of trade and defense: Wampanoags with Plymouth; Mohegans with Massachusetts and Connecticut; Pequots with New Netherland; Narragansetts with Rhode Island.

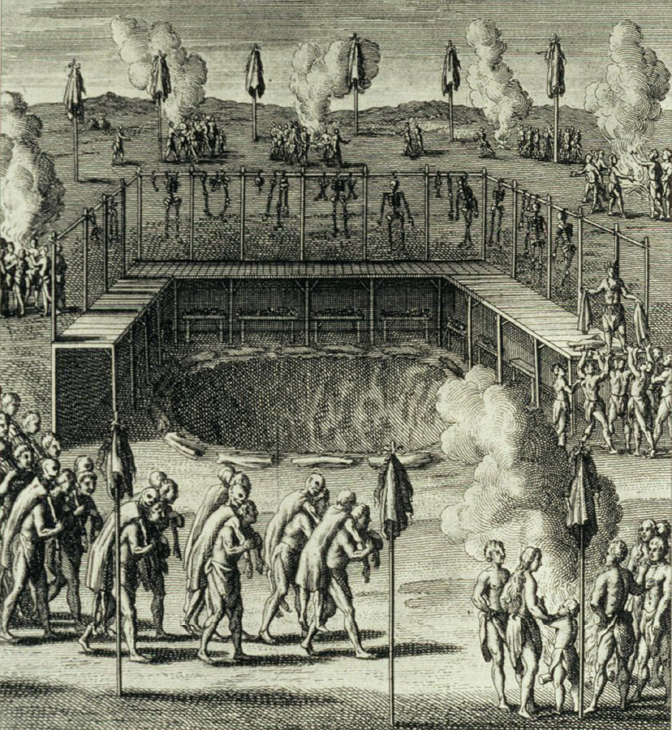

Puritan-Pequot War Because of their alliance with the Dutch, the Pequots became a thorn in the side of English traders. A series of violent encounters began in July 1636 with the killing of English trader John Oldham and escalated until May 1637, when a combined force of Massachusetts and Connecticut militiamen, accompanied by Narragansett and Mohegan warriors, attacked a Pequot village and massacred some five hundred men, women, and children. In the months that followed, the New Englanders drove the surviving Pequots into oblivion and divided their lands.

Believing they were God’s chosen people, Puritans considered their presence to be divinely ordained. Initially, they pondered the morality of acquiring Native American lands. “By what right or warrant can we enter into the land of the Savages?” they asked themselves. Responding to such concerns, John Winthrop detected God’s hand in a recent smallpox epidemic: “If God were not pleased with our inheriting these parts,” he asked, “why doth he still make roome for us by diminishing them as we increase?” Experiences like the Pequot War confirmed New Englanders’ confidence in their enterprise. “God laughed at the Enemies of his People,” one soldier boasted after the 1637 massacre, “filling the Place with Dead Bodies.”

Like Catholic missionaries, Puritans believed that their church should embrace all peoples. However, their strong emphasis on predestination — the idea that God saved only a few chosen people — made it hard for them to accept that Indians could be counted among the elect. “Probably the devil” delivered these “miserable savages” to America, Cotton Mather suggested, “in hopes that the gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ would never come here.” A few Puritan ministers committed themselves to the effort to convert Indians. On Martha’s Vineyard, Jonathan Mayhew helped to create an Indian-led community of Wampanoag Christians. John Eliot translated the Bible into Algonquian and created fourteen Indian praying towns. By 1670, more than 1,000 Indians lived in these settlements, but relatively few Native Americans were ever permitted to become full members of Puritan congregations.

Metacom’s War, 1675–1676 By the 1670s, Europeans in New England outnumbered Indians by three to one. The English population had multiplied to 55,000, while native peoples had diminished from an estimated 120,000 in 1570 to barely 16,000. To the Wampanoag leader Metacom (also known as King Philip), the prospects for coexistence looked dim. When his people copied English ways by raising hogs and selling pork in Boston, Puritan officials accused them of selling at “an under rate” and restricted their trade. When Indians killed wandering hogs that devastated their cornfields, authorities prosecuted them for violating English property rights (American Voices).

Metacom concluded that the English colonists had to be expelled. In 1675, the Wampanoags’ leader forged a military alliance with the Narragansetts and Nipmucks and attacked white settlements throughout New England. Almost every day, settler William Harris fearfully reported, he heard new reports of the Indians’ “burneing houses, takeing cattell, killing men & women & Children: & carrying others captive.” Bitter fighting continued into 1676, ending only when the Indian warriors ran short of gunpowder and the Massachusetts Bay government hired Mohegan and Mohawk warriors, who killed Metacom.

Metacom’s War of 1675–1676 (which English settlers called King Philip’s War) was a deadly affair. Indians destroyed one-fifth of the English towns in Massachusetts and Rhode Island and killed 1,000 settlers, nearly 5 percent of the adult population; for a time the Puritan experiment hung in the balance. But the natives’ losses — from famine and disease, death in battle, and sale into slavery — were much larger: about 4,500 Indians died, one-quarter of an already diminished population. Many of the surviving Wampanoag, Narragansett, and Nipmuck peoples moved west, intermarrying with Algonquian tribes allied to the French. Over the next century, these displaced Indian peoples would take their revenge, joining with French Catholics to attack their Puritan enemies. Metacom’s War did not eliminate the presence of Native Americans in southern New England, but it effectively destroyed their existence as independent peoples.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

How did New Englanders’ religious ideas influence their relations with neighboring Native American peoples?