America’s History: Printed Page 43

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 36

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 35

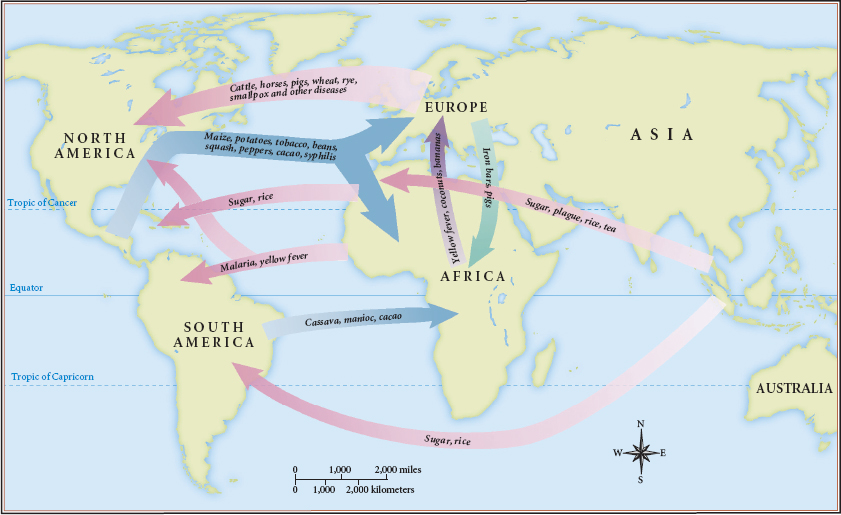

The Columbian Exchange

The Spanish invasion permanently altered the natural as well as the human environment. Smallpox, influenza, measles, yellow fever, and other silent killers carried from Europe and Africa ravaged Indian communities, whose inhabitants had never encountered these diseases before and thus had no immunity to them. In the densely populated core areas, populations declined by 90 percent or more in the first century of contact with Europeans. On islands and in the tropical lowlands, the toll was even heavier; native populations were often wiped out altogether. Syphilis was the only significant illness that traveled in the opposite direction: Columbus’s sailors carried a virulent strain of the sexually transmitted disease back to Europe with them.

The movement of diseases and peoples across the Atlantic was part of a larger pattern of biological transformation that historians call the Columbian Exchange (Map 2.1). Foods of the Western Hemisphere — especially maize, potatoes, manioc, sweet potatoes, and tomatoes — significantly increased agricultural yields and population growth in other continents. Maize and potatoes, for example, reached China around 1700; in the following century, the Chinese population tripled from 100 million to 300 million. At the same time, many animals, plants, and germs were carried to the Americas. European livestock transformed American landscapes. While Native Americans domesticated very few animals — dogs and llamas were the principal exceptions — Europeans brought an enormous Old World bestiary to the Americas, including cattle, swine, horses, oxen, chickens, and honeybees. Eurasian grain crops — wheat, barley, rye, and rice — made the transatlantic voyage along with inadvertent imports like dandelions and other weeds.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

How did the ecological context of colonization shape interactions between Europeans and Native Americans?