America’s History: Printed Page 977

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 887

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 868

The Carter Presidency

First, the Republican Party had to defeat incumbent president Jimmy Carter. Carter’s outsider status and his disdain for professional politicians had made him the ideal post-Watergate president. But his ineffectiveness and missteps as an executive also made him the perfect foil for Ronald Reagan.

Carter had an idealistic vision of American leadership in world affairs. He presented himself as the anti-Nixon, a world leader who rejected Henry Kissinger’s “realism” in favor of human rights and peacemaking. “Human rights is the soul of our foreign policy,” Carter asserted, “because human rights is the very soul of our sense of nationhood.” He established the Office of Human Rights in the State Department and withdrew economic and military aid from repressive regimes in Argentina, Uruguay, and Ethiopia — although, in realist fashion, he still funded equally repressive U.S. allies such as the Philippines, South Africa, and Iran. In Latin America, Carter eliminated a decades-old symbol of Yankee imperialism by signing a treaty on September 7, 1977, turning control of the Panama Canal over to Panama (effective December 31, 1999). Carter’s most important efforts came in forging an enduring, although in retrospect limited, peace in the intractable Arab-Israeli conflict. In 1978, he invited Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian president Anwar el-Sadat to Camp David, where they crafted a “framework for peace,” under which Egypt recognized Israel and received back the Sinai Peninsula, which Israel had occupied since 1967.

Carter deplored what he called the “inordinate fear of communism,” but his efforts at improving relations with the Soviet Union foundered. His criticism of the Kremlin’s record on human rights offended Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and slowed arms reduction negotiations. When, in 1979, Carter finally signed the second Strategic Arms Limitations Treaty (SALT II), limiting bombers and missiles, Senate hawks objected. Then, when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan that December, Carter suddenly endorsed the hawks’ position and treated the invasion as the “gravest threat to world peace since World War II.” After ordering an embargo on wheat shipments to the Soviet Union and withdrawing SALT II from Senate consideration, Carter called for increased defense spending and declared an American boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow. In a fateful decision, he and Congress began providing covert assistance to anti-Soviet fighters in Afghanistan, some of whom, including Osama bin Laden, would metamorphose into anti-American Islamic radicals decades later.

Hostage Crisis Carter’s ultimate undoing came in Iran, however. The United States had long counted Iran as a faithful ally, a bulwark against Soviet expansion into the Middle East and a steady source of oil. Since the 1940s, Iran had been ruled by Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. Ousted by a democratically elected parliament in the early 1950s, the shah (king) sought and received the assistance of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which helped him reclaim power in 1953. American intervention soured Iranian views of the United States for decades. Early in 1979, a revolution drove the shah into exile and brought a fundamentalist Shiite cleric, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, to power (Shiites represent one branch of Islam, Sunnis the other). When the United States admitted the deposed shah into the country for cancer treatment, Iranian students seized the U.S. embassy in Tehran, taking sixty-six Americans hostage. The captors demanded that the shah be returned to Iran for trial. Carter refused. Instead, he suspended arms sales to Iran and froze Iranian assets in American banks.

For the next fourteen months, the hostage crisis paralyzed Carter’s presidency. Night after night, humiliating pictures of blindfolded American hostages appeared on television newscasts. An attempt to mount a military rescue in April 1980 had to be aborted because of equipment failures in the desert. Several months later, however, a stunning development changed the calculus on both sides: Iraq, led by Saddam Hussein, invaded Iran, officially because of a dispute over deep-water ports but also to prevent the Shiite-led Iranian Revolution from spreading across the border into Sunni-run Iraq. Desperate to focus his nation’s attention on Iraq’s invasion, Khomeini began to talk with the United States about releasing the hostages. Difficult negotiations dragged on past the American presidential election in November 1980, and the hostages were finally released the day after Carter left office — a final indignity endured by a well-intentioned but ineffectual president.

The Election of 1980 President Carter’s sinking popularity hurt his bid for reelection. When the Democrats barely renominated him over his liberal challenger, Edward (Ted) Kennedy of Massachusetts, Carter’s approval rating was historically low: a mere 21 percent of Americans believed that he was an effective president. The reasons were clear. Economically, millions of citizens were feeling the pinch from stagnant wages, high inflation, crippling mortgage rates, and an unemployment rate of nearly 8 percent. In international affairs, the nation blamed Carter for his weak response to Soviet expansion and the Iranians’ seizure of American diplomats.

With Carter on the defensive, Reagan remained upbeat and decisive. “This is the greatest country in the world,” Reagan reassured the nation in his warm baritone voice. “We have the talent, we have the drive. … All we need is the leadership.” To emphasize his intention to be a formidable international leader, Reagan hinted that he would take strong action to win the hostages’ return. To signal his rejection of liberal policies, he declared his opposition to affirmative action and forced busing and promised to “get the government off our backs.” Most important, Reagan effectively appealed to the many Americans who felt financially insecure. In a televised debate with Carter, Reagan emphasized the hardships facing working- and middle-class Americans in an era of stagflation and asked them: “Are you better off today than you were four years ago?”

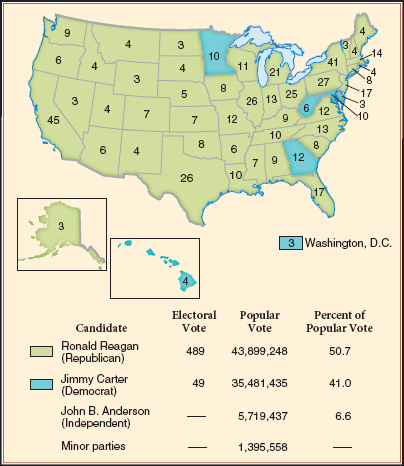

In November, the voters gave a clear answer. They repudiated Carter, giving him only 41.0 percent of the vote. Independent candidate John Anderson garnered 6.6 percent (with a few minor candidates receiving fractions of a percent), and Reagan won with 50.7 percent of the popular vote (Map 30.1). Moreover, the Republicans elected thirty-three new members of the House of Representatives and twelve new senators, which gave them control of the U.S. Senate for the first time since 1954. The New Right’s long road to national power had culminated in an election victory that signaled a new political alignment in the country.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

In terms of presidential politics and policy, how successful was Jimmy Carter’s term, coming between two Republicans (Nixon and Reagan)?