America’s History: Printed Page 992

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 901

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 879

U.S.-Soviet Relations in a New Era

When Reagan assumed the presidency in 1981, he broke with his immediate predecessors — Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter — in Cold War strategy. Nixon regarded himself as a “realist” in foreign affairs. That meant, above all, advancing the national interest without regard to ideology. Nixon’s policy of détente with the Soviet Union and China embodied this realist view. President Carter endorsed détente and continued to push for relaxing Cold War tensions. This worked for a time, but the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan empowered hard-liners in the U.S. Congress and forced Carter to take a tougher line — which he did with the Olympic boycott and grain embargo. This was the relationship Reagan inherited in 1981: a decade of détente that had produced a noticeable relaxation of tensions with the communist world, followed by a year of tense standoffs over Soviet advances into Central Asia, which threatened U.S. interests in the Middle East.

Reagan’s Cold War Revival Conservatives did not believe in détente. Neither did they believe in the containment policy that had guided U.S. Cold War strategy since 1947. Reagan and his advisors wanted to defeat, not merely contain, the Soviet Union. His administration pursued a two-pronged strategy toward that end. First, it abandoned détente and set about rearming America. Reagan’s military budgets authorized new weapons systems, dramatically expanded military bases, and significantly expanded the nation’s nuclear arsenal. This buildup in American military strength, reasoned Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger, would force the Soviets into an arms race that would strain their economy and cause domestic unrest. One of the most controversial aspects of the buildup was Reagan’s proposal for a Strategic Defense Initiative — popularly known as “Star Wars” — a satellite-based system that would, theoretically, destroy nuclear missiles in flight. Scientists doubted its viability, and it was never built. The Reagan administration also proposed the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START) with the Soviet Union, in which the United States put forward a plan calculated to increase American advantage in sea- and air-based nuclear systems over the Soviet’s ground-based system.

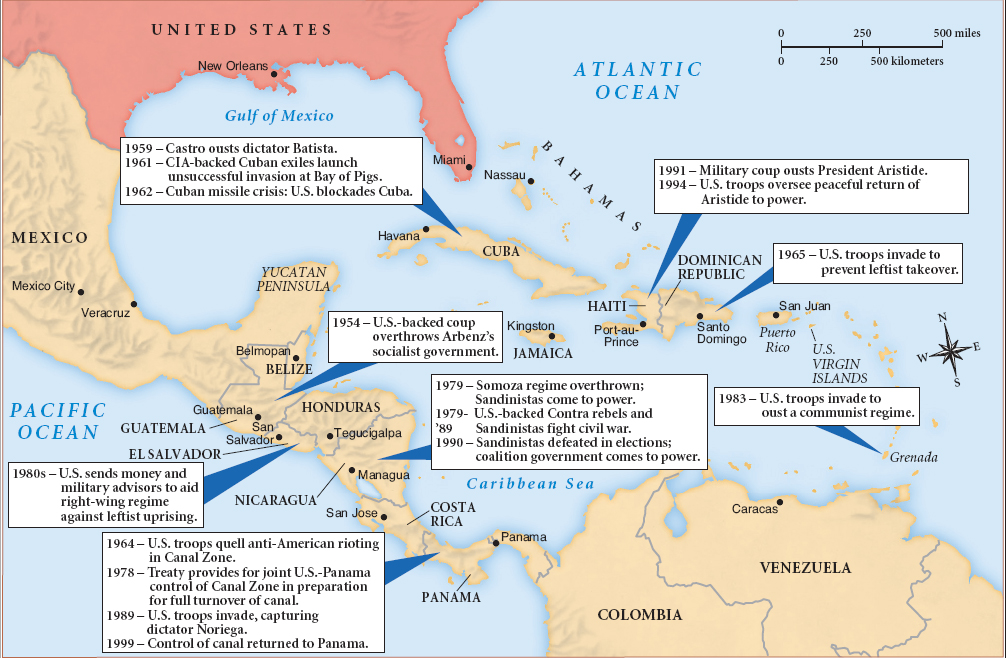

Second, the president supported CIA initiatives to roll back Soviet influence in the developing world by funding anticommunist movements in Angola, Mozambique, Afghanistan, and Central America. To accomplish this objective, Reagan supported repressive, right-wing regimes. Nowhere was this more conspicuous in the 1980s than in the Central American countries of Guatemala, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. Conditions were unique in each country but held to a pattern: the United States sided with military dictatorships and oligarchies if democratically elected governments or left-wing movements sought support from the Soviet Union. In Guatemala, this approach produced a brutal military rule — thousands of opponents of the government were executed or kidnapped. In Nicaragua, Reagan actively encouraged a coup against the left-wing Sandinista government, which had overthrown the U.S.-backed strongman Anastasio Somoza. And in El Salvador, the U.S.-backed government maintained secret “death squads,” which murdered members of the opposition. In each case, Reagan blocked Soviet influence, but the damage done to local communities and to the international reputation of the United States, as in Vietnam, was great.

Iran-Contra Reagan’s determination to oppose left-wing movements in Central America engulfed his administration in a major scandal during the president’s second term. For years, Reagan had denounced Iran as an “outlaw state” and a supporter of terrorism. But in 1985, he wanted its help. To win Iran’s assistance in freeing two dozen American hostages held by Hezbollah, a pro-Iranian Shiite group in Lebanon, the administration sold arms to Iran without public or congressional knowledge. While this secret arms deal was diplomatically and politically controversial, the use of the resulting profits in Nicaragua was explicitly illegal. To overthrow the democratically elected Sandinistas, whom the president accused of threatening U.S. business interests, Reagan ordered the CIA to assist an armed opposition group called the Contras (Map 30.2). Although Reagan praised the Contras as “freedom fighters,” Congress worried that the president and other executive branch agencies were assuming war-making powers that the Constitution reserved to the legislature. In 1984, Congress banned the CIA and all other government agencies from providing any military support to the Contras.

Oliver North, a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Marines and an aide to the National Security Council, defied that ban. With the tacit or explicit consent of high-ranking administration officials, including the president, North used the profits from the Iranian arms deal to assist the Contras. When asked whether he knew of North’s illegal actions, Reagan replied, “I don’t remember.” The Iran-Contra affair not only resulted in the prosecution of North and several other officials but also weakened Reagan domestically — he proposed no bold domestic policy initiatives in his last two years. But the president remained steadfastly engaged in international affairs, where events were unfolding that would bring a dramatic close to the Cold War.

Gorbachev and Soviet Reform The Soviet system of state socialism and central economic planning had transformed Russia from an agricultural to an industrial society between 1917 and the 1950s. But it had done so inefficiently. Lacking the incentives of a market economy, most enterprises hoarded raw materials, employed too many workers, and did not develop new products. Except in military weaponry and space technology, the Russian economy fell further and further behind those of capitalist societies, and most people in the Soviet bloc endured a low standard of living. Moreover, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, like the American war in Vietnam, turned out to be a major blunder — an unwinnable war that cost vast amounts of money, destroyed military morale, and undermined popular support of the government.

Mikhail Gorbachev, a relatively young Russian leader who became general secretary of the Communist Party in 1985, recognized the need for internal economic reform and an end to the war in Afghanistan. An iconoclast in Soviet terms, Gorbachev introduced policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (economic restructuring), which encouraged widespread criticism of the rigid institutions and authoritarian controls of the Communist regime. To lessen tensions with the United States, Gorbachev met with Reagan in 1985, and the two leaders established a warm personal rapport. By 1987, they had agreed to eliminate all intermediate-range nuclear missiles based in Europe. A year later, Gorbachev ordered Soviet troops out of Afghanistan, and Reagan replaced many of his hard-line advisors with policymakers who favored a renewal of détente. Reagan’s sudden reversal with regard to the Soviet Union remains one of the most intriguing aspects of his presidency. Many conservatives worried that their cowboy-hero president had been duped by a duplicitous Gorbachev, but Reagan’s gamble paid off: the easing of tensions with the United States allowed the Soviet leader to press forward with his domestic reforms.

As Gorbachev’s efforts revealed the flaws of the Soviet system, the peoples of Eastern and Central Europe demanded the ouster of their Communist governments. In Poland, the Roman Catholic Church and its pope — Polish-born John Paul II — joined with Solidarity, the trade union movement, to overthrow the pro-Soviet regime. In 1956 and 1964, Russian troops had quashed similar popular uprisings in Hungary and East Germany. Now they did not intervene, and a series of peaceful uprisings — “Velvet Revolutions” — created a new political order throughout the region. The destruction of the Berlin Wall in 1989 symbolized the end of Communist rule in Central Europe. Millions of television viewers worldwide watched jubilant Germans knock down the hated wall that had divided the city since 1961 — a vivid symbol of communist repression and the Cold War division of Europe. A new geopolitical order in Europe was in the making.

Alarmed by the reforms, Soviet military leaders seized power in August 1991 and arrested Gorbachev. But widespread popular opposition led by Boris Yeltsin, the president of the Russian Republic, thwarted their efforts to oust Gorbachev from office. This failure broke the dominance of the Communist Party. On December 25, 1991, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics formally dissolved to make way for an eleven-member Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). The Russian Republic assumed leadership of the CIS, but the Soviet Union was no more (Map 30.3). The collapse of the Soviet Union was the result of internal weaknesses of the Communist economy. External pressure from the United States played an important, though secondary, role.

“Nobody — no country, no party, no person — ‘won’ the cold war,” concluded George Kennan, the architect in 1947 of the American policy of containment. The Cold War’s cost was enormous, and both sides benefitted greatly from its end. For more than forty years, the United States had fought a bitter economic and ideological battle against that communist foe, a struggle that exerted an enormous impact on American society. Taxpayers had spent some $4 trillion on nuclear weapons and trillions more on conventional arms, placing the United States on a permanent war footing and creating a massive military-industrial complex. The physical and psychological costs were equally high: radiation from atomic weapons tests, anticommunist witch-hunts, and a constant fear of nuclear annihilation. Of course, most Americans had no qualms about proclaiming victory, and advocates of free-market capitalism, particularly conservative Republicans, celebrated the outcome. The collapse of communism in Eastern Europe and the disintegration of the Soviet Union itself, they argued, demonstrated that they had been right all along.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

How did Reagan’s approach to the Soviet Union change between 1981 and 1989?