America’s History: Printed Page 975

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 886

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 866

Free-Market Economics and Religious Conservatism

The last phase of Reagan’s rise was the product of several additional developments within the New Right. The burgeoning conservative movement increasingly resembled a three-legged stool. Each leg represented an ideological position and a popular constituency: anticommunism, free-market economics, and religious traditionalism. Uniting all three in a political coalition was no easy feat. Religious traditionalists demanded strong government action to implement their faith-based agenda, while economic conservatives favored limited government and free markets. Both groups, however, were ardent anticommunists — free marketeers loathed the state-directed Soviet economy, and religious conservatives despised the “godless” secularism of the Soviet state. In the end, the success of the New Right would come to depend on balancing the interests of economic and moral conservatives.

Since the 1950s, William F. Buckley, the founder and editor of the conservative magazine National Review, and Milton Friedman, the Nobel Prize-winning economist at the University of Chicago, had been the most prominent conservative intellectuals. Convinced that “the growth of government must be fought relentlessly,” Buckley used the National Review to criticize liberal policy. For his part, Friedman became a national conservative icon with the publication of Capitalism and Freedom (1962), in which he argued that “economic freedom is … an indispensable means toward the achievement of political freedom.” Friedman’s free-market ideology, along with that of Friedrich von Hayek, another University of Chicago economist, was taken up by wealthy conservatives, who funded think tanks during the 1980s to disseminate market-based public policy ideas. The Heritage Foundation, the American Enterprise Institute, and the Cato Institute issued policy proposals and attacked liberal legislation and the stranglehold of economic regulation they believed it exerted. Followers of Buckley and Friedman envisioned themselves as crusaders, working against what one conservative called “the despotic aspects of egalitarianism.”

The most striking addition to the conservative coalition was the Religious Right. Until the 1970s, politics was an earthly concern of secondary interest to most fundamentalist and evangelical Protestants. But the perception that American society had become immoral, combined with the influence of a new generation of popular ministers, made politics relevant. Conservative Protestants and Catholics joined together in a tentative alliance, as the Religious Right condemned divorce, abortion, premarital sex, and feminism. The route to a moral life and to “peace, pardon, purpose, and power,” as one evangelical activist said, was “to plug yourself into the One, the Only One [God].”

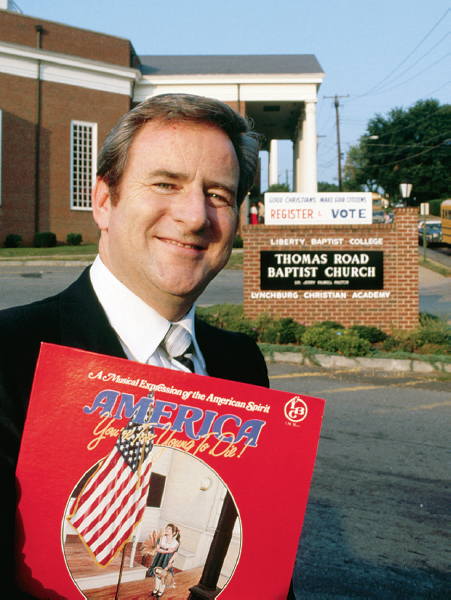

Charismatic televangelists such as Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell emerged as the champions of a morality-based political agenda during the late 1970s. Falwell, founder of Liberty University and host of the Old Time Gospel Hour television program, established the Moral Majority in 1979. With 400,000 members and $1.5 million in contributions in its first year, it would be the organizational vehicle for transforming the Fourth Great Awakening into a religious political movement. Falwell made no secret of his views: “If you want to know where I am politically,” he told reporters, “I thought Goldwater was too liberal.” Falwell was not alone. Phyllis Schlafly’s STOP ERA, which became Eagle Forum in 1975, continued to advocate for conservative public policy; Focus on the Family was founded in 1977; and a succession of conservative organizations would emerge in the 1980s, including the Family Research Council.

The conservative message preached by Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan had appealed to few American voters in 1964. Then came the series of events that undermined support for the liberal agenda of the Democratic Party: the failed war in Vietnam; a judiciary that legalized abortion and pornography, enforced school busing, and curtailed public expression of religion; urban riots; and a stagnating economy. By the late 1970s, the New Right had developed a conservative message that commanded much greater popular support than Goldwater’s program had. Religious and free-market conservatives joined with traditional anticommunist hard-liners — alongside whites opposed to black civil rights, affirmative action, and busing — in a broad coalition that attacked welfare-state liberalism, social permissiveness, and an allegedly weak and defensive foreign policy. Ronald Reagan expertly appealed to all of these conservative constituencies and captured the Republican presidential nomination in 1980 (American Voices). It had taken almost two decades, but the New Right appeared on the verge of winning the presidency.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

What was the “three-legged stool” of the New Right, and how did each leg develop within the context of the Cold War?