America’s History: Printed Page 1013

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 918

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 896

An Increasingly Plural Society

Exact estimates vary, but demographers predict that at some point between 2040 and 2050 the United States will become a “majority-minority” nation: No single ethnic or racial group will be in the numerical majority. This is already the case in California, where in 2010 African Americans, Latinos, and Asians together constituted a majority of the state’s residents. As this unmistakable trend became apparent in the 1990s, it fueled renewed debates over ethnic and racial identity and over public policies such as affirmative action.

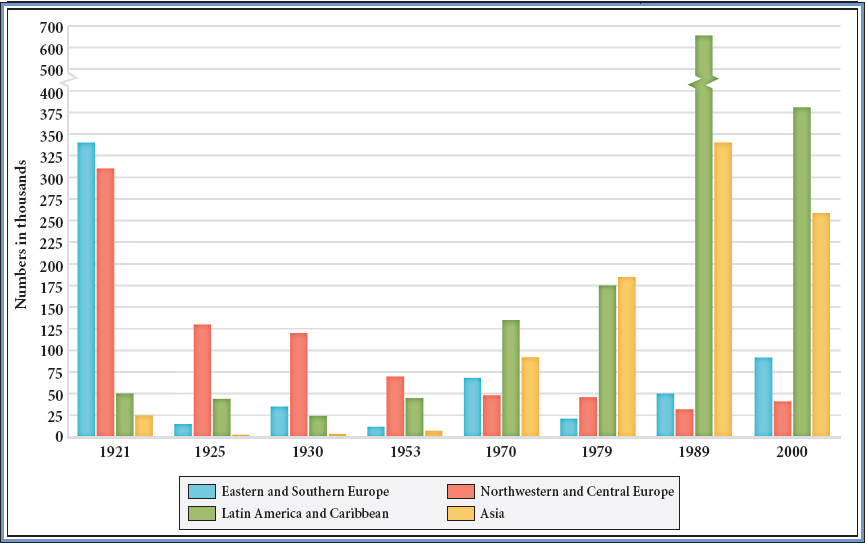

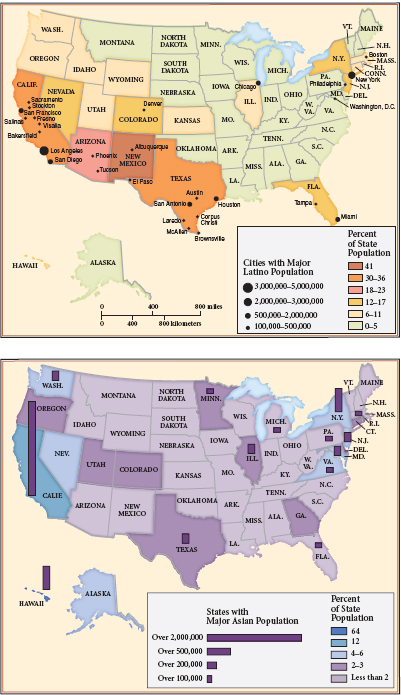

New Immigrants According to the Census Bureau, the population of the United States grew from 203 million in 1970 to 280 million in 2000 (American Voices). Of that 77-million-person increase, immigrants accounted for 28 million, with legal entrants numbering 21 million and illegal entrants adding another 7 million (Figure 31.5). As a result, by 2000, 26 percent of California’s population was foreign-born, as was 20 percent of New York’s and 17 percent each of New Jersey’s and Florida’s. Relatively few immigrants came from Europe, which had dominated immigration to the United States between 1880 and 1924. The overwhelming majority — some 25 million — now came from Latin America (16 million) and East Asia (9 million) (Map 31.2).

This extraordinary inflow of immigrants was the unintended result of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, one of the less well-known but most influential pieces of Great Society legislation. Known as the Hart-Celler Act, the legislation eliminated the 1924 quota system, which had favored Northern Europe. In its place, Congress created a more equal playing field among nations and a slightly higher total limit on immigration. The legislation also included provisions that eased the entry of immigrants who possessed skills in high demand in the United States. Finally, a provision with far-reaching implications was included in the new law: immediate family members of those already legally resident in the United States were admitted outside of the total numerical limit.

American residents from Latin America and the Caribbean were best positioned to take advantage of the family provision. Millions of Mexicans came to the United States to join their families, and U.S. residents from El Salvador and Guatemala — tens of thousands of whom had arrived seeking sanctuary or asylum during the civil wars of the 1980s — and the Dominican Republic now brought their families to join them. Nationally, there were now more Latinos than African Americans. Many of these immigrants profoundly shaped the emerging global economy by sending substantial portions of their earnings, called remittances, back to family members in their home countries. In 2006, for instance, workers in the United States sent $23 billion to Mexico, a massive remittance flow that constituted Mexico’s third-largest source of foreign exchange.

Asian immigrants came largely from China, the Philippines, South Korea, India, and Pakistan. In addition, 700,000 refugees came to the United States from Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) after the Vietnam War. This immigration signaled more than new flows of people into the United States. Throughout much of its history, the United States had oriented itself toward the Atlantic. Indeed, at the end of the nineteenth century, American secretary of state John Hay observed, “The Mediterranean is the ocean of the past; the Atlantic the ocean of the present.” He added, presciently, “The Pacific [is] the ocean of the future.” By the last decades of the twentieth century, Hay’s future had arrived. As immigration from Asia increased, as Japan and China grew more influential economically, and as more and more transnational trade crossed the Pacific, commentators on both sides of the ocean began speaking of the Pacific Rim as an important new region.

Multiculturalism and Its Critics Most new immigrants arrived under the terms of the 1965 law. But those who entered without legal documentation stirred political controversy. After twenty years under the new law, there were three to five million immigrants without legal status. In 1986, to remedy this situation, Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act. The law granted citizenship to many of those who had arrived illegally, provided incentives for employers not to hire undocumented immigrants, and increased surveillance along the border with Mexico. Immigration critics persisted, however. In 1992, Patrick Buchanan, then campaigning for the Republican presidential nomination, warned Americans that their country was “undergoing the greatest invasion in its history, a migration of millions of illegal aliens a year from Mexico.” Many states took immigration matters into their own hands. In 1994, for instance, Californians approved Proposition 187, a ballot initiative that barred illegal aliens from public schools, nonemergency care at public health clinics, and all other state social services. The proposed law declared that U.S. citizens have a “right to the protection of their government from any person or persons entering this country unlawfully,” but after five years in federal court, the controversial measure was ruled unconstitutional.

|

To see a longer excerpt of Proposition 187, along with other primary sources from this period, see Sources for America’s History. |

Debates over post-1965 immigration looked a great deal like conflicts in the early decades of the century. Then, many native-born white Protestants worried that the largely Jewish and Catholic immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, along with African American migrants leaving the South, could not assimilate and threatened the “purity” of the nation. Although the conflicts looked the same, the cultural paradigm had shifted. In the earlier era, the melting pot — a term borrowed from the title of a 1908 play — became the metaphor for how American society would accommodate its newfound diversity. Some native-born Americans found solace in the melting-pot concept because it implied that a single “American” culture would predominate. In the 1990s, however, a different concept, multiculturalism, emerged to define social diversity. Americans, this concept suggested, were not a single people into whom others melted; rather, they comprised a diverse set of ethnic and racial groups living and working together. A shared set of public values held the multicultural society together, even as different groups maintained unique practices and traditions.

Critics, however, charged that multiculturalism perpetuated ethnic chauvinism and conferred preferential treatment on minority groups. Many government policies, as well as a large number of private employers, for instance, continued to support affirmative action programs designed to bring African Americans and Latinos into public- and private-sector jobs and universities in larger numbers. Conservatives argued that such governmental programs were deeply flawed because they promoted “reverse discrimination” against white men and women and resulted in the selection and promotion of less qualified applicants for jobs and educational advancement.

California stood at the center of the debate. In 1995, under pressure from Republican governor Pete Wilson, the regents of the University of California scrapped their twenty-year-old policy of affirmative action. A year later, California voters approved Proposition 209, which outlawed affirmative action in state employment and public education. At the height of the 1995 controversy, President Bill Clinton delivered a major speech defending affirmative action. He reminded Americans that Richard Nixon, a Republican president, had endorsed affirmative action, and he concluded by saying the nation should “mend it,” not “end it.” However, as in the Bakke decision of the 1970s, it was the U.S. Supreme Court that spoke loudest on the subject. In two parallel 2003 cases, the Court invalidated one affirmative action plan at the University of Michigan but allowed racial preference policies that promoted a “diverse” student body. Thus diversity became the law of the land, the constitutionally acceptable basis for affirmative action. The policy had been narrowed but preserved.

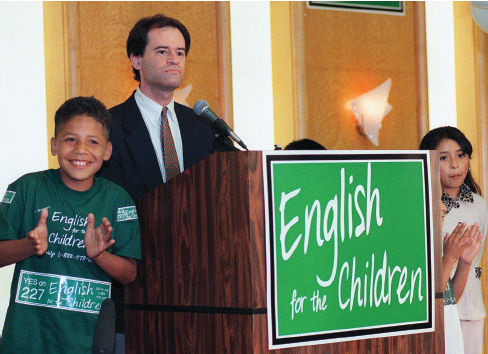

Additional anxieties about a multicultural nation centered on language. In 1998, Silicon Valley software entrepreneur Ron Unz sponsored a California initiative calling for an end to bilingual education in public schools. Unz argued that bilingual education had failed because it did not adequately prepare Spanish-speaking students to succeed in an English-speaking society. The state’s white, Anglo residents largely approved of the measure; most Mexican American, Asian American, and civil rights organizations opposed it. When Unz’s measure, Proposition 227, passed with a healthy 61 percent majority, it seemed to confirm the limits of multiculturalism in the nation’s most diverse state.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

How did anti-immigrant sentiment increase between the 1960s and the 1990s, and what sorts of actions were taken by those opposed to immigration?