America’s History: Printed Page 1020

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 926

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 902

The Clinton Presidency, 1993–2001

The culture wars contributed to a new, divisive partisanship in national politics. Rarely in the twentieth century had the two major parties so adamantly refused to work together. Also rare was the vitriolic rhetoric that politicians used to describe their opponents. The fractious partisanship was filtered through — or, many would argue, created by — the new twenty-four-hour cable news television networks, such as Fox News and CNN. Commentators on these channels, finding that nothing drew viewers like aggressive partisanship, increasingly abandoned their roles as conveyors of information and became entertainers and provocateurs.

That divisiveness was a hallmark of the presidency of William Jefferson Clinton. In 1992, Clinton, the governor of Arkansas, styled himself a New Democrat who would bring Reagan Democrats and middle-class voters back to the party. Only forty-six, he was an energetic, ambitious policy wonk — extraordinarily well informed about the details of public policy. To win the Democratic nomination in 1992, Clinton had to survive charges that he embodied the permissive social values conservatives associated with the 1960s: namely, that he dodged the draft to avoid service in Vietnam, smoked marijuana, and cheated repeatedly on his wife. The charges were damaging, but Clinton adroitly talked his way into the presidential nomination: he had charisma and a way with words. For his running mate, he chose Albert A. Gore, a senator from Tennessee. Gore was about the same age as Clinton, making them the first baby-boom national ticket as well as the nation’s first all-southern major-party ticket.

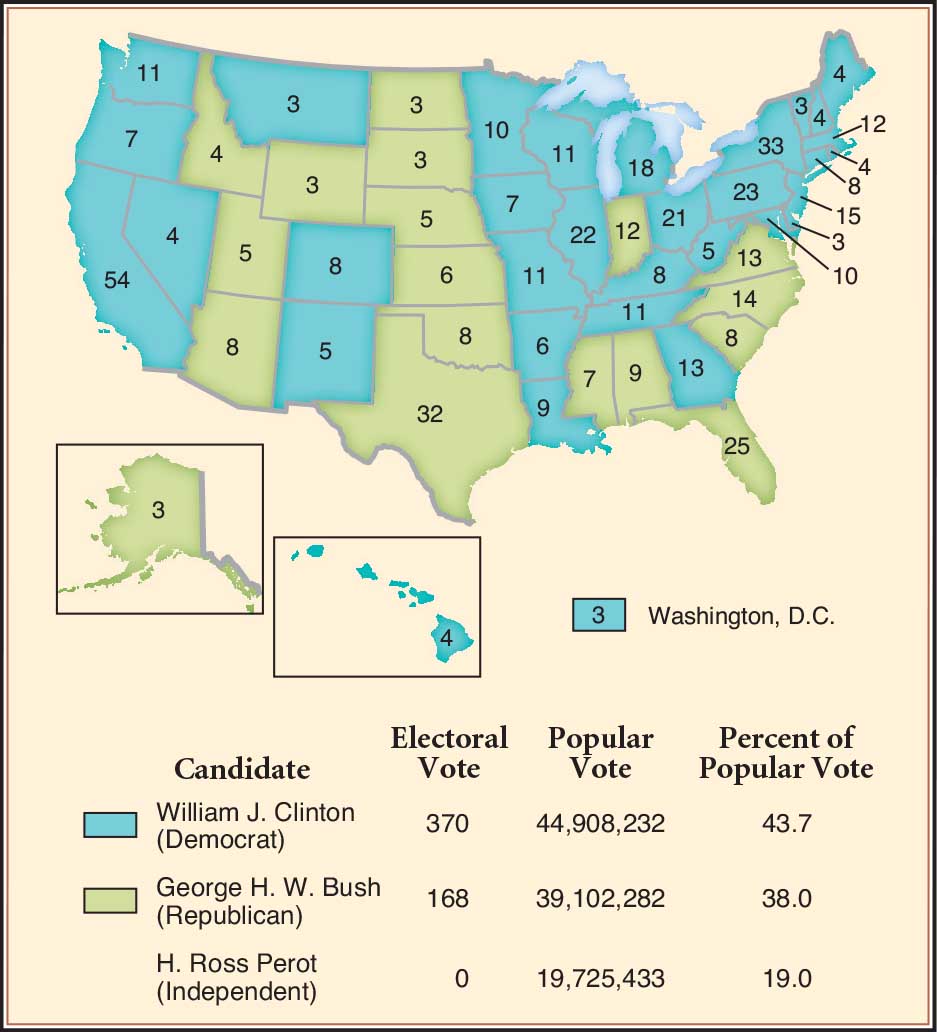

President George H. W. Bush won renomination over his lone opponent, the conservative columnist Pat Buchanan. The Democrats mounted an aggressive campaign that focused on Clinton’s domestic agenda: he promised a tax cut for the middle class, universal health insurance, and a reduction of the huge Republican budget deficit. It was an audacious combination of traditional social-welfare liberalism and fiscal conservatism. For his part, Bush could not overcome voters’ discontent with the weak economy and conservatives’ disgust at his tax hikes. He received only 38.0 percent of the popular vote as millions of Republicans cast their ballots for independent businessman Ross Perot, who won more votes (19.0 percent) than any independent candidate since Theodore Roosevelt in 1912. With 43.7 percent of the vote, Clinton won the election (Map 31.3). Still, there were reasons for him to worry. Among all post-World War II presidents, only Richard Nixon (in 1969) entered the White House with a comparably small share of the national vote.

New Democrats and Public Policy Clinton tried to steer a middle course through the nation’s increasingly divisive partisanship. On his left was the Democratic Party’s weakened but still vocal liberal wing. On his right were party moderates influenced by Reagan-era notions of reducing government regulation and the welfare state. Clinton’s “third way,” as he dubbed it, called for the new president to tailor his proposals to satisfy these two quite different — and often antagonistic — political constituencies. Clinton had notable successes as well as spectacular failures pursuing this course.

The spectacular failure came first. Clinton’s most ambitious social-welfare goal was to provide a system of health care that would cover all Americans and reduce the burden of health-care costs on the larger economy. Although the United States spent a higher percentage of its gross national product (GNP) on medical care than any other nation, it was the only major industrialized country that did not provide government-guaranteed health insurance to all citizens. It was an objective that had eluded every Democratic president since Harry Truman.

Recognizing the potency of Reagan’s attack on “big government,” Clinton’s health-care task force — led by First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton — proposed a system of “managed competition.” Private insurance companies and market forces were to rein in health-care expenditures. The cost of this system would fall heavily on employers, and many smaller businesses campaigned strongly against it. So did the health insurance industry and the American Medical Association, powerful lobbies with considerable influence in Washington. By mid-1994, Democratic leaders in Congress declared that the Clintons’ universal health-care proposal was dead. Forty million Americans, or 15 percent of the population, remained without health insurance coverage.

More successful was Clinton’s plan to reduce the budget deficits of the Reagan-Bush presidencies. In 1993, Clinton secured a five-year budget package that would reduce the federal deficit by $500 billion. Republicans unanimously opposed the proposal because it raised taxes on corporations and wealthy individuals, and liberal Democrats complained because it limited social spending. But shared sacrifice led to shared rewards. By 1998, Clinton’s fiscal policies had balanced the federal budget and begun to pay down the federal debt — at a rate of $156 billion a year between 1999 and 2001. As fiscal sanity returned to Washington, the economy boomed, thanks in part to the low interest rates stemming from deficit reduction.

The Republican Resurgence The midterm election of 1994 confirmed that the Clinton presidency had not produced an electoral realignment: conservatives still had a working majority. In a well-organized campaign, in which grassroots appeals to the New Right dominated, Republicans gained fifty-two seats in the House of Representatives, giving them a majority for the first time since 1954. They also retook control of the Senate and captured eleven governorships. Leading the Republican charge was Representative Newt Gingrich of Georgia, who revived calls for significant tax cuts, reductions in welfare programs, anticrime initiatives, and cutbacks in federal regulations. These initiatives, which Gingrich promoted under the banner of a “Contract with America,” had been central components of the conservative-backed Reagan Revolution of the 1980s, but Gingrich believed that under the presidency of George H. W. Bush Republicans had not emphasized them enough.

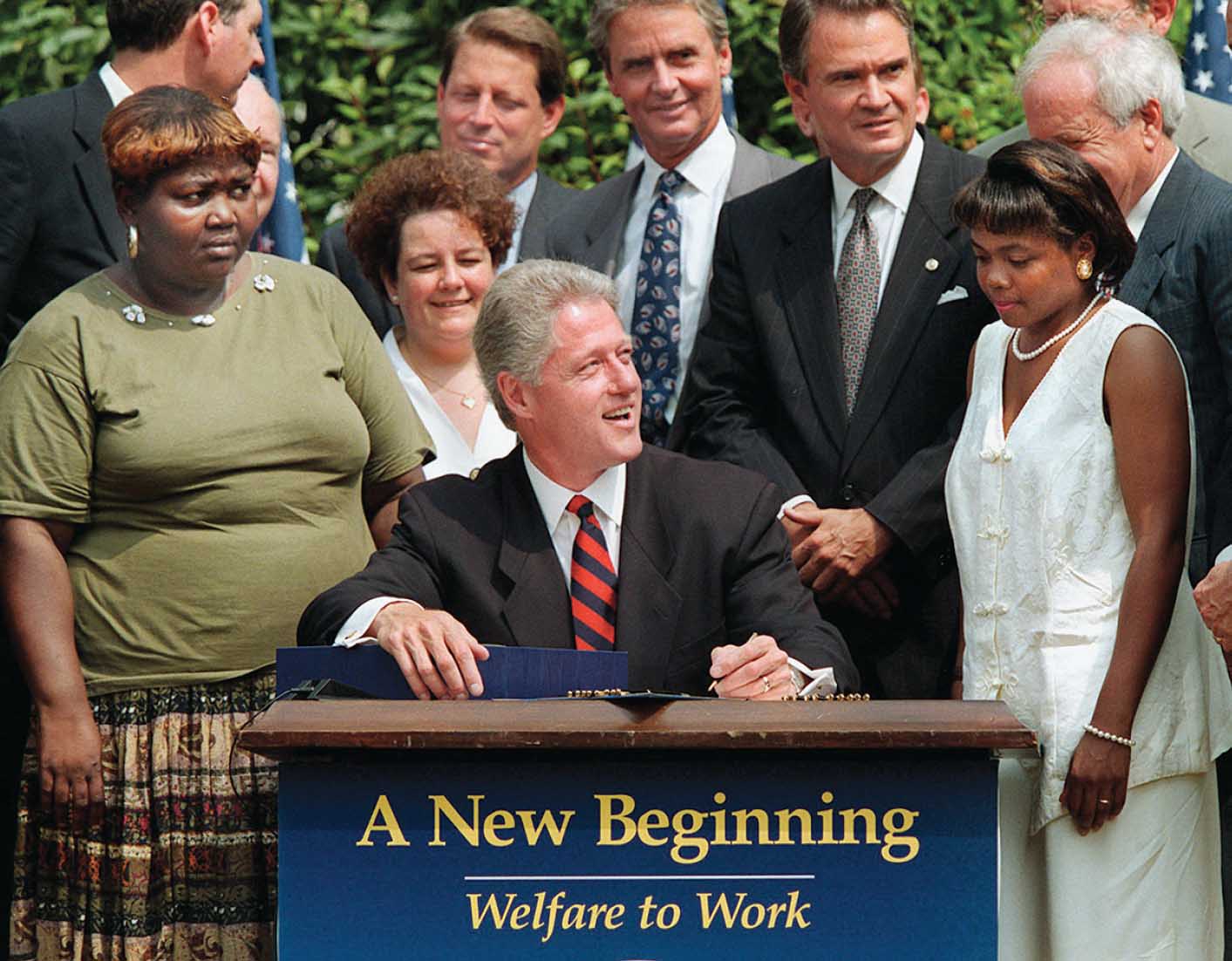

In response to the massive Democratic losses in 1994, Clinton moved to the right. Claiming in 1996 that “the era of big government is over,” he avoided expansive social-welfare proposals for the remainder of his presidency and sought Republican support for a centrist New Democrat program. The signal piece of that program was reforming the welfare system, a measure that saved relatively little money but carried a big ideological message. Many taxpaying Americans believed — with some supporting evidence — that the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program encouraged female recipients to remain on welfare rather than seek employment. In August 1996, the federal government abolished AFDC, achieving a long-standing goal of conservatives when Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act. Liberals were furious with the president.

Clinton’s Impeachment Following a relatively easy victory in the 1996 election, Clinton’s second term unraveled when a sex scandal led to his impeachment. Clinton denied having had a sexual affair with Monica Lewinsky, a former White House intern. Independent prosecutor Kenneth Starr, a conservative Republican, concluded that Clinton had committed perjury and obstructed justice and that these actions were grounds for impeachment. Viewed historically, Americans have usually defined “high crimes and misdemeanors” — the constitutional standard for impeachment — as involving a serious abuse of public trust that endangered the republic. In 1998, conservative Republicans favored a much lower standard because they did not accept Clinton’s legitimacy as president. They vowed to oust him from office for lying about an extramarital affair.

On December 19, the House of Representatives narrowly approved two articles of impeachment. Only a minority of Americans supported the House’s action; according to a CBS News poll, 38 percent favored impeachment while 58 percent opposed it. Lacking public support, in early 1999 Republicans in the Senate fell well short of the two-thirds majority they needed to remove the president. But like Andrew Johnson, the only other president to be tried by the Senate, Clinton and the Democratic Party paid a high price for his acquittal. Preoccupied with defending himself, the president was unable to fashion a Democratic alternative to the Republicans’ domestic agenda. The American public also paid a high price, because the Republicans’ vendetta against Clinton drew attention away from pressing national problems.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

What made President Clinton a “New Democrat,” and how much did his proposals differ from traditional liberal objectives?