America’s History: Printed Page 1030

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 937

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 913

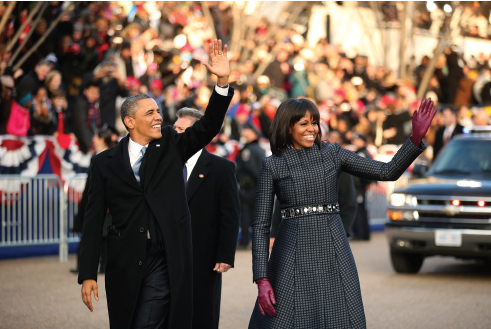

The Obama Presidency

During his campaign for the presidency against Republican senator John McCain, Barack Obama, a Democratic senator from Illinois, established himself as a unique figure in American politics. The son of an African immigrant-student and a young white woman from Kansas, Obama was raised in Hawaii and Indonesia, and he easily connected with an increasingly multiracial and multicultural America. A generation younger than Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, Obama (born in 1961) seemed at once a product of the 1960s, especially civil rights gains, and outside its heated conflicts.

Obama took the oath of office of the presidency on January 21, 2009, amid the deepest economic recession since the Great Depression and with the United States mired in two wars in the Middle East. From the podium, the new president recognized the crises and worried about “a nagging fear that America’s decline is inevitable.” But Obama also hoped to strike an optimistic tone. Americans, he said, must “begin again the work of remaking America.”

“Remaking America” A nation that a mere two generations ago would not allow black Americans to dine with white Americans had elected a black man to the highest office. Obama himself was less taken with this historic accomplishment — which was also part of his deliberate strategy to downplay race — than with developing a plan to deal with the nation’s innumerable challenges, at home and abroad. With explicit comparisons to Franklin Roosevelt, Obama used the “first hundred days” of his presidency to lay out an ambitious agenda: an economic stimulus package of federal spending to invigorate the economy; plans to draw down the war in Iraq and refocus American military efforts in Afghanistan; a reform of the nation’s health insurance system; and new federal laws to regulate Wall Street.

Remarkably, the president accomplished much of that agenda. The Democratic-controlled Congress elected alongside Obama passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, an economic stimulus bill that provided $787 billion to state and local governments for schools, hospitals, and transportation projects (roads, bridges, and rail) — one of the largest single packages of government spending in American history. Congress next passed the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, a complex law that added new regulations limiting the financial industry and new consumer protections. Political debate over both measures was heated. Critics on the left argued that Obama and Congress had been too cautious, given the scale of the nation’s problems, while those on the right decried both laws as irresponsible government interference in private investment.

Political debate was fiercest, however, over Obama’s health insurance reform proposal. Obama encouraged congressional Democrats to put forth their own proposals, while he worked to find Republican allies who might be persuaded to support the first major reform of the nation’s health-care system since the introduction of Medicare in 1965. None came forward. Moreover, as debate dragged on, a set of far-right opposition groups, known collectively as the Tea Party, emerged. Giving voice to the extreme individualism and antigovernment sentiment traditionally associated with right-wing movements in the United States, the Tea Party rallied Americans against Obama’s health-care bill. Despite the opposition, the legislation (officially called the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act) passed, and Obama signed it into law on March 23, 2010. However, political opposition and the powerful lobbying of the private health insurance industry ensured that the new law contained enough compromises that few could predict its long-term impact.

Following the legislative victories of his first two years in office, President Obama faced a divided Congress. Democrats lost control of the House of Representatives in 2010 and failed to regain it in 2012. With the legislative process stalled, Obama used executive authority to advance his broader, cautiously liberal, agenda. In 2011, for instance, the president repealed the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy and ordered that gay men and lesbians be allowed to serve openly in the armed forces. And he made two appointments to the Supreme Court: Sonia Sotomayor in 2009, the first Latina to serve on the high court, and Elena Kagan in 2010. Both Sotomayor and Kagan are committed liberals, though they serve on a Court that has shifted to the right under Chief Justice John Roberts, a George W. Bush appointee.

War and Instability in the Middle East Even as he pursued an ambitious domestic agenda, Obama faced two wars in the Middle East that he inherited from his predecessor. Determined to end American occupation of Iraq, the president began in 2010 to draw down troops stationed there, and the last convoy of U.S. soldiers departed in late 2011. The nine-year war in Iraq, begun to find alleged weapons of mass destruction, had followed a long and bloody arc to its end. Disengaging from Afghanistan proved more difficult. Early in his first term, the president ordered an additional 30,000 American troops to parts of the country where the Taliban had regained control — a “surge” he believed necessary to avoid further Taliban victories. Securing long-term political stability in this fractious nation, however, has eluded Obama. Leaving with the least damage done was his only viable option, and he pledged to withdraw all U.S. troops by 2014.

Meanwhile, a host of events in the Middle East deepened the region’s volatility. In late 2010, a series of multicountry demonstrations and protests, dubbed the Arab Spring, began to topple some of the region’s autocratic rulers. Leaders in Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, and Yemen were forced from power by mass movements calling for greater democracy. These movements, which the Obama administration has cautiously supported, continue to reverberate in more than a dozen nations in the Middle East. Not long after the Arab Spring was under way, in May 2011, U.S. Special Forces found and killed Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan, where he had been hiding for many years. Obama received much praise for the tactics that led to the discovery of bin Laden. More controversial has been the president’s use of “drone” strikes to assassinate Al Qaeda leaders and other U.S. enemies in the region.

Climate Change American wars and other involvement in the Middle East hinged on the region’s centrality to global oil production. Oil is important in another sense, however: its role in climate change. Scientists have known for decades that the production of energy through the burning of carbon-based substances (especially petroleum and coal) increases the presence of so-called greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, warming the earth. Increasing temperatures will produce dramatically new weather patterns and rising sea levels, developments that threaten agriculture, the global distributions of plant and animal life, and whole cities and regions at or near the current sea level. How to halt, or at least mitigate, climate change has been one of the most pressing issues of the twenty-first century.

Arriving at a scientific consensus on climate change has proven easier than developing government policies to address it. This has been especially true in the United States, where oil company lobbyists, defenders of free-market capitalism, and conservatives who deny global warming altogether have been instrumental in blocking action. For instance, the United States is not a signatory to the major international treaty — the so-called Kyoto Protocol — that is designed to reduce carbon emissions. Legislative proposals have not fared better. Cap-and-trade legislation, so named because it places a cap on individual polluters’ emissions but allows those companies to trade for more emission allowances from low polluters, has stalled in Congress. Another proposal, a tax on carbon emissions, has likewise gained little political support. There is little doubt, however, that global climate change, and the role of the United States in both causing and mitigating it, will remain among the most critical questions of the next decades.

Electoral Shifts It remains to be seen how the Obama presidency will affect American politics. From one vantage point, Obama looks like the beneficiary of an electoral shift in a liberal direction. Since 1992, Democrats have won the popular vote in five of the last six presidential elections, and in 2008 Obama won a greater share of the popular vote (nearly 53 percent) than either Clinton (who won 43 percent in 1992 and 49 percent in 1996) or Gore (48 percent in 2000). In his bid for reelection in 2012 against Republican nominee Mitt Romney, Obama won a lower percentage of the popular vote (51 percent) but still won by a comfortable margin of nearly 5 million votes. He won the support of 93 percent of African Americans, 71 percent of Hispanics, 73 percent of Asian Americans, 55 percent of women, and 60 percent of Americans under the age of thirty. His coalition was multiracial, heavily female, and young.

From another vantage point, any electoral shift toward liberalism appears contingent and fragile. Even with Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress that rivaled Franklin Roosevelt’s in 1937 and Lyndon Johnson’s in 1965, Obama in 2009–2010 was not able to generate political momentum for the kind of legislative advances achieved by those presidential forerunners. The history of Obama’s presidency, and of the early twenty-first century more broadly, continues to unfold.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

As the nation’s first African American president, what kinds of unique challenges did Barack Obama face, and how did these issues impact his presidency?