America’s History: Printed Page 80

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 69

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 66

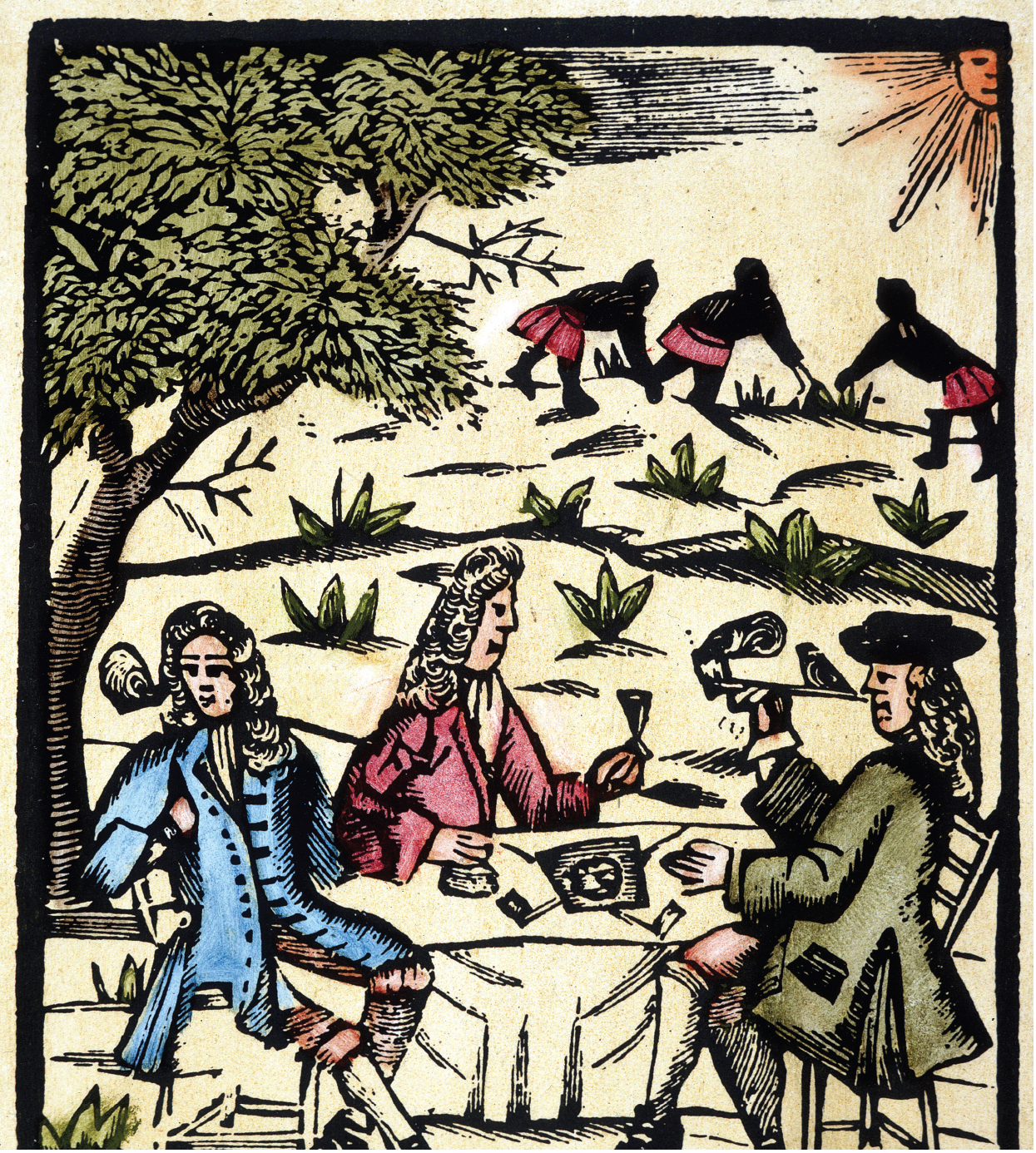

The British Atlantic World

1660–1750

3

CHAPTER

IDENTIFY THE BIG IDEA

How did the South Atlantic System create an interconnected Atlantic World, and how did this system impact development in the British colonies?

For two weeks in June 1744, the town of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, hosted more than 250 Iroquois men, women, and children for a diplomatic conference with representatives from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. Crowds of curious observers thronged Lancaster’s streets and courthouse. The conference grew out of a diplomatic system between the colonies and the Iroquois designed to air grievances and resolve conflict: the Covenant Chain. Participants welcomed each other, exchanged speeches, and negotiated agreements in public ceremonies whose minutes became part of the official record of the colonies.

At Lancaster, the colonies had much to ask of their Iroquois allies. For one thing, they wanted them to confirm a land agreement. The Iroquois often began such conferences by resisting land deals; as the Cayuga orator Gachradodon said, “You know very well, when the White people came first here they were poor; but now they have got our Lands, and are by them become rich, and we are now poor; what little we have had for the Land goes soon away, but the Land lasts forever.” In the end, however, they had little choice but to accept merchandise in exchange for land, since colonial officials were unwilling to take no for an answer. The colonists also announced that Britain was once again going to war with France, and they requested military support from their Iroquois allies. Canassatego — a tall, commanding Onondaga orator, about sixty years old, renowned for his eloquence — replied, “We shall never forget that you and we have but one Heart, one Head, one Eye, one Ear, and one Hand. We shall have all your Country under our Eye, and take all the Care we can to prevent any Enemy from coming into it.”

|

To see a longer excerpt of the Canassatego document, along with other primary sources from this period, see Sources for America’s History. |

The Lancaster conference — and dozens of others like it that occurred between 1660 and 1750 — demonstrates that the British colonies, like those of France and Spain, relied ever more heavily on alliances with Native Americans as they sought to extend their power in North America. Indian nations remade themselves in these same years, creating political structures — called “tribes” by Europeans — that allowed them to regroup in the face of population decline and function more effectively alongside neighboring colonies. The colonies, meanwhile, were drawn together into an integrated economic sphere — the South Atlantic System — that brought prosperity to British North America, while they achieved a measure of political autonomy that became essential to their understanding of what it meant to be British subjects.