America’s History: Printed Page 92

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 79

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 77

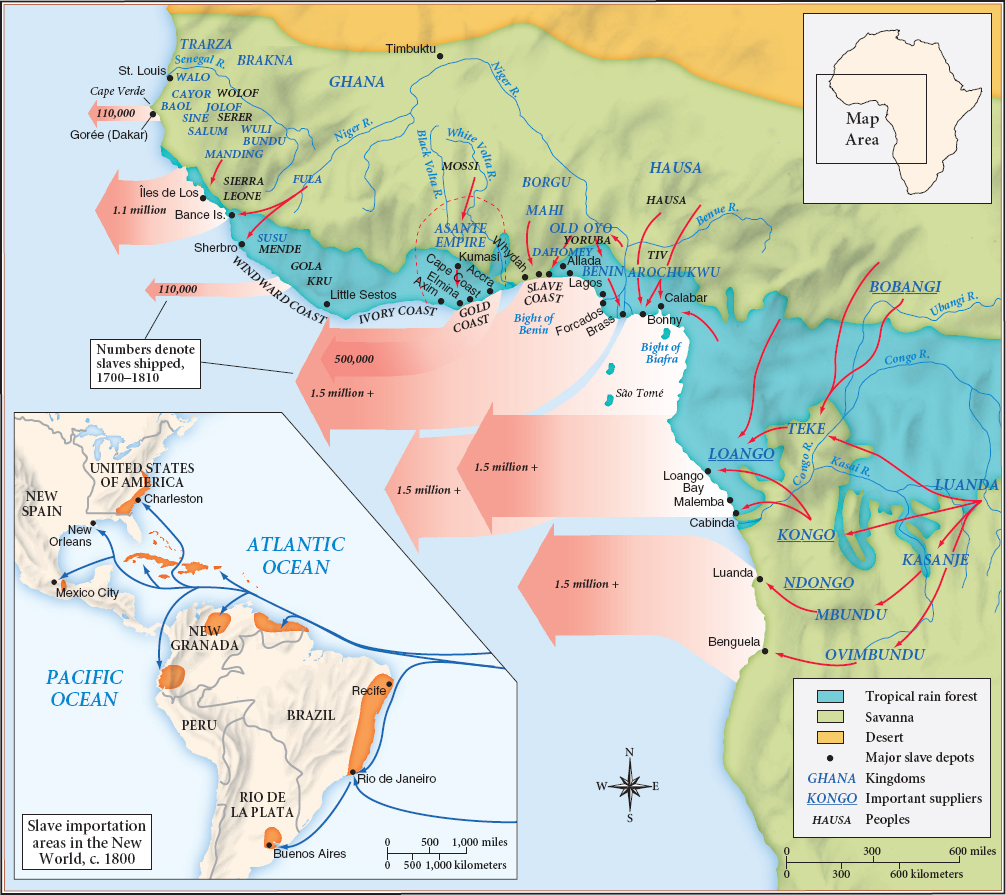

Africa, Africans, and the Slave Trade

As the South Atlantic System enhanced European prosperity, it imposed enormous costs on West and Central Africa. Between 1550 and 1870, the Atlantic slave trade uprooted 11 million Africans, draining lands south of the Sahara of people and wealth and changing African society (Map 3.3). By directing commerce away from the savannas and the Islamic world on the other side of the Sahara, the Atlantic slave trade changed the economic and religious dynamics of the African interior. It also fostered militaristic, centralized states in the coastal areas.

Africans and the Slave Trade Warfare and slaving had been part of African life for centuries, but the South Atlantic System made slaving a favorite tactic of ambitious kings and plundering warlords. “Whenever the King of Barsally wants Goods or Brandy,” an observer noted, “the King goes and ransacks some of his enemies’ towns, seizing the people and selling them.” Supplying slaves became a way of life in the West African state of Dahomey, where the royal house monopolized the sale of slaves and used European guns to create a military despotism. Dahomey’s army, which included a contingent of 5,000 women, raided the interior for captives; between 1680 and 1730, Dahomey annually exported 20,000 slaves from the ports of Allada and Whydah. The Asante kings likewise used slaving to conquer states along the Gold Coast as well as Muslim kingdoms in the savanna. By the 1720s, they had created a prosperous empire of 3 to 5 million people. Yet participation in the transatlantic slave trade remained a choice for Africans, not a necessity. The powerful kingdom of Benin, famous for its cast bronzes and carved ivory, prohibited for decades the export of all slaves, male and female. Other Africans atoned for their guilt for selling neighbors into slavery by building hidden shrines, often in the household granary.

The trade in humans produced untold misery. Hundreds of thousands of young Africans died, and millions more endured a brutal life in the Americas. In Africa itself, class divisions hardened as people of noble birth enslaved and sold those of lesser status. Gender relations shifted as well. Two-thirds of the slaves sent across the Atlantic were men, partly because European planters paid more for men and “stout men boys” and partly because Africans sold enslaved women locally and across the Sahara as agricultural workers, house servants, and concubines. The resulting sexual imbalance prompted African men to take several wives, changing the meaning of marriage. Finally, the expansion of the Atlantic slave trade increased the extent of slavery in Africa. Sultan Mawlay Ismail of Morocco (r. 1672–1727) owned 150,000 black slaves, obtained by trade in Timbuktu and in wars he waged in Senegal. In Africa, as in the Americas, slavery eroded the dignity of human life.

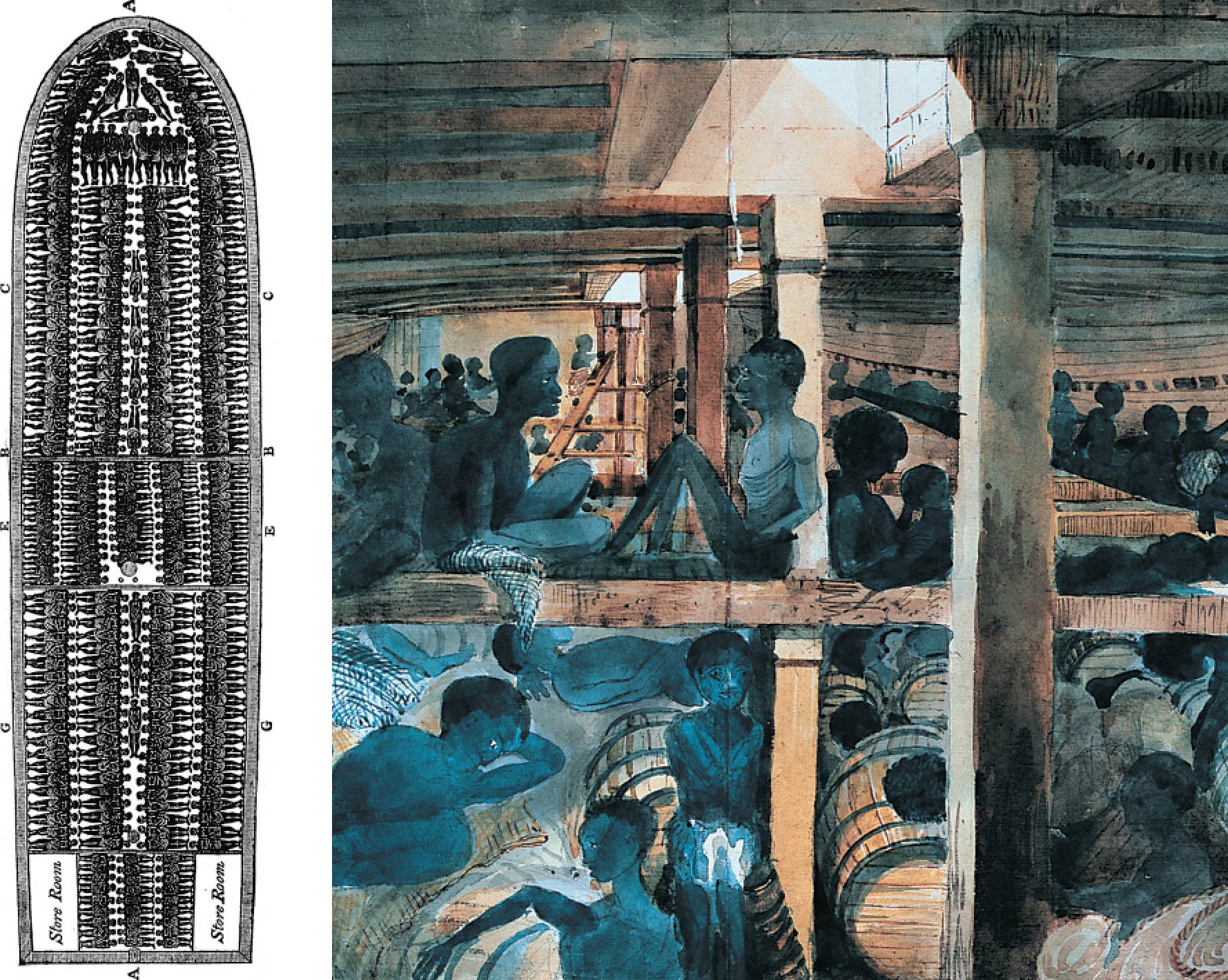

The Middle Passage and Beyond Africans sold into the South Atlantic System suffered the bleakest fate. Torn from their villages, they were marched in chains to coastal ports, their first passage in slavery. Then they endured the perilous Middle Passage to the New World in hideously overcrowded ships. The captives had little to eat or drink, and some died from dehydration. The feces, urine, and vomit belowdecks prompted outbreaks of dysentery, which took more lives. “I was so overcome by the heat, stench, and foul air that I nearly fainted,” reported a European doctor. Some slaves jumped overboard to drown rather than endure more suffering. Others staged violent shipboard revolts. Slave uprisings occurred on two thousand voyages, roughly one of every ten Atlantic passages. Nearly 100,000 slaves died in these insurrections, and nearly 1.5 million others — about 14 percent of those who were transported — died of disease or illness on the month-long journey (America Compared).

For those who survived the Atlantic crossing, things only got worse as they passed into endless slavery. Life on the sugar plantations of northwestern Brazil and the West Indies was one of relentless exploitation. Slaves worked ten hours a day under the hot tropical sun; slept in flimsy huts; and lived on a starchy diet of corn, yams, and dried fish. They were subjected to brutal discipline: “The fear of punishment is the principle [we use] … to keep them in awe and order,” one planter declared. When punishments came, they were brutal. Flogging was commonplace; some planters rubbed salt, lemon juice, or urine into the resulting wounds.

Planters often took advantage of their power by raping enslaved women. Sexual exploitation was a largely unacknowledged but ubiquitous feature of master-slave relations: something that many slave masters considered to be an unquestioned privilege of their position. “It was almost a constant practice with our clerks, and other whites,” Olaudah Equiano wrote, “to commit violent depredations on the chastity of the female slaves.” Thomas Thistlewood was a Jamaica planter who kept an unusually detailed journal in which he noted every act of sexual exploitation he committed. In thirty-seven years as a Jamaica planter, Thistlewood recorded 3,852 sex acts with 138 enslaved women.

With sugar prices high and the cost of slaves low, many planters simply worked their slaves to death and then bought more. Between 1708 and 1735, British planters on Barbados imported about 85,000 Africans; however, in that same time the island’s black population increased by only 4,000 (from 42,000 to 46,000). The constant influx of new slaves kept the population thoroughly “African” in its languages, religions, and culture. “Here,” wrote a Jamaican observer, “each different nation of Africa meet and dance after the manner of their own country … [and] retain most of their native customs.”