America’s History: Printed Page 96

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 83

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 80

Slavery in the Chesapeake and South Carolina

West Indian-style slavery came to Virginia and Maryland following Bacon’s Rebellion. Taking advantage of the expansion of the British slave trade (following the end of the Royal African Company’s monopoly in 1698), elite planter-politicians led a “tobacco revolution” and bought more Africans, putting these slaves to work on ever-larger plantations. By 1720, Africans made up 20 percent of the Chesapeake population; by 1740, nearly 40 percent. Slavery had become a core institution, no longer just one of several forms of unfree labor. Moreover, slavery was now defined in racial terms. Virginia legislators prohibited sexual intercourse between English and Africans and defined virtually all resident Africans as slaves: “All servants imported or brought into this country by sea or land who were not Christians in their native country shall be accounted and be slaves.”

On the mainland as in the islands, slavery was a system of brutal exploitation. Violence was common, and the threat of violence always hung over master-slave relationships. In 1669, Virginia’s House of Burgesses decreed that a master who killed a slave in the process of “correcting” him could not be charged with a felony, since it would be irrational to destroy his own property. From that point forward, even the most extreme punishments were permitted by law. Slaves could not carry weapons or gather in large numbers. Slaveholders were especially concerned to discourage slaves from running away. Punishments for runaways commonly included not only brutal whipping but also branding or scarring to make recalcitrant slaves easier to identify. Virginia laws spelled out the procedures for capturing and returning runaway slaves in detail. If a runaway slave was killed in the process of recapturing him, the county would reimburse the slave’s owner for his full value. In some cases, slave owners could choose to put runaway slaves up for trial; if they were found guilty and executed, the owner would be compensated for his loss (Thinking Like a Historian).

Despite the inherent brutality of the institution, slaves in Virginia and Maryland worked under better conditions than those in the West Indies. Many lived relatively long lives. Unlike sugar and rice, which were “killer crops” that demanded strenuous labor in a tropical climate, tobacco cultivation required steadier and less demanding labor in a more temperate environment. Workers planted young tobacco seedlings in spring, hoed and weeded the crop in summer, and in fall picked and hung the leaves to cure over the winter. Nor did diseases spread as easily in the Chesapeake, because plantation quarters were less crowded and more dispersed than those in the West Indies. Finally, because tobacco profits were lower than those from sugar, planters treated their slaves less harshly than West Indian planters did.

Many tobacco planters increased their workforce by buying female slaves and encouraging them to have children. In 1720, women made up more than one-third of the Africans in Maryland, and the black population had begun to increase naturally. “Be kind and indulgent to the breeding wenches,” one slave owner told his overseer, “[and do not] force them when with child upon any service or hardship that will be injurious to them.” By midcentury, more than three-quarters of the enslaved workers in the Chesapeake were American-born.

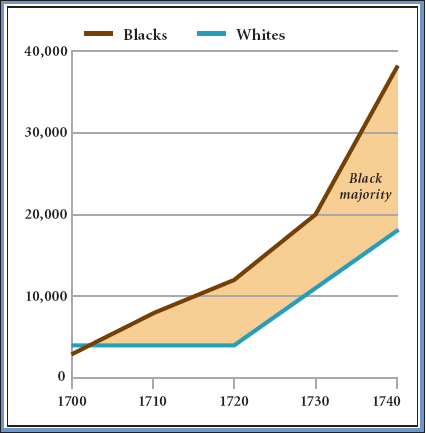

Slaves in South Carolina labored under much more oppressive conditions. The colony grew slowly until 1700, when planters began to plant and export rice to southern Europe, where it was in great demand. Between 1720 and 1750, rice production increased fivefold. To expand production, planters imported thousands of Africans, some of them from rice-growing societies. By 1710, Africans formed a majority of the total population, eventually rising to 80 percent in rice-growing areas (Figure 3.2).

Most rice plantations lay in inland swamps, and the work was dangerous and exhausting. Slaves planted, weeded, and harvested the rice in ankle-deep mud. Pools of stagnant water bred mosquitoes, which transmitted diseases that claimed hundreds of African lives. Other slaves, forced to move tons of dirt to build irrigation works, died from exhaustion. “The labour required [for growing rice] is only fit for slaves,” a Scottish traveler remarked, “and I think the hardest work I have seen them engaged in.” In South Carolina, as in the West Indies and Brazil, there were many slave deaths and few births, and the arrival of new slaves continually “re-Africanized” the black population.