America’s History: Printed Page 129

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 112

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 109

American Pietism and the Great Awakening

As some colonists turned to deism, thousands of others embraced Pietism, a Christian movement originating in Germany around 1700 and emphasizing pious behavior (hence the name). In its emotional worship services and individual striving for a mystical union with God, Pietism appealed to believers’ hearts rather than their minds (American Voices). In the 1720s, German migrants carried Pietism to America, sparking a religious revival (or renewal of religious enthusiasm) in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, where Dutch minister Theodore Jacob Frelinghuysen preached passionate sermons to German settlers and encouraged church members to spread the message of spiritual urgency. A decade later, William Tennent and his son Gilbert copied Frelinghuysen’s approach and led revivals among Scots-Irish Presbyterians throughout the Middle Atlantic region.

New England Revivalism Simultaneously, an American-born Pietist movement appeared in New England. Revivals of Christian zeal were built into the logic of Puritanism. In the 1730s, Jonathan Edwards, a minister in Northampton, Massachusetts, encouraged a revival there that spread to towns throughout the Connecticut River Valley. Edwards guided and observed the process and then published an account entitled A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God, printed first in London (1737), then in Boston (1738), and then in German and Dutch translations. Its publication history highlights the transatlantic network of correspondents that gave Pietism much of its vitality.

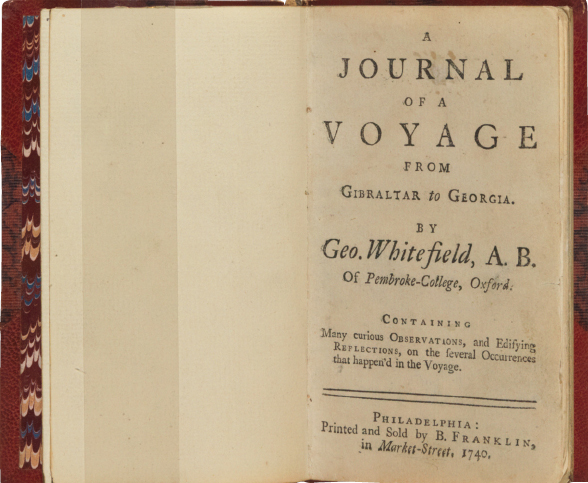

Whitefield’s Great Awakening English minister George Whitefield transformed the local revivals of Edwards and the Tennents into a Great Awakening. After Whitefield had his personal awakening upon reading the German Pietists, he became a follower of John Wesley, the founder of English Methodism. In 1739, Whitefield carried Wesley’s fervent message to America, where he attracted huge crowds from Georgia to Massachusetts.

Whitefield had a compelling presence. “He looked almost angelical; a young, slim, slender youth … cloathed with authority from the Great God,” wrote a Connecticut farmer. Like most evangelical preachers, Whitefield did not read his sermons but spoke from memory. More like an actor than a theologian, he gestured eloquently, raised his voice for dramatic effect, and at times assumed a female persona — as a woman in labor struggling to deliver the word of God. When the young preacher told his spellbound listeners that they had sinned and must seek salvation, some suddenly felt a “new light” within them. As “the power of god come down,” Hannah Heaton recalled, “my knees smote together … [and] it seemed to me I was a sinking down into hell … but then I resigned my distress and was perfectly easy quiet and calm … [and] it seemed as if I had a new soul & body both.” Strengthened and self-confident, these converts, the so-called New Lights, were eager to spread Whitefield’s message.

The rise of print intersected with this enthusiasm. “Religion is become the Subject of most Conversations,” the Pennsylvania Gazette reported. “No books are in Request but those of Piety and Devotion.” Whitefield and his circle did their best to answer the demand for devotional reading. As he traveled, Whitefield regularly sent excerpts of his journal to be printed in newspapers. Franklin printed Whitefield’s sermons and journals by subscription and found them to be among his best-selling titles. Printed accounts of Whitefield’s travels, conversion narratives, sermons, and other devotional literature helped to confirm Pietists in their faith and strengthen the communication networks that sustained them.