America’s History: Printed Page 157

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 138

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 136

Formal Protests and the Politics of the Crowd

Virginia’s House of Burgesses was the first formal body to complain. In May 1765, hotheaded young Patrick Henry denounced Grenville’s legislation and attacked George III for supporting it. He compared the king to Charles I, whose tyranny had led to his overthrow and execution in the 1640s. These remarks, which bordered on treason, frightened the Burgesses; nonetheless, they condemned the Stamp Act’s “manifest Tendency to Destroy American freedom.” In Massachusetts, James Otis, another republican-minded firebrand, persuaded the House of Representatives to call a meeting of all the mainland colonies “to implore Relief” from the act.

The Stamp Act Congress Nine assemblies sent delegates to the Stamp Act Congress, which met in New York City in October 1765. The congress protested the loss of American “rights and liberties,” especially the right to trial by jury. And it challenged the constitutionality of both the Stamp and Sugar Acts by declaring that only the colonists’ elected representatives could tax them. Still, moderate-minded delegates wanted compromise, not confrontation. They assured Parliament that Americans “glory in being subjects of the best of Kings” and humbly petitioned for repeal of the Stamp Act. Other influential Americans favored active (but peaceful) resistance; they organized a boycott of British goods.

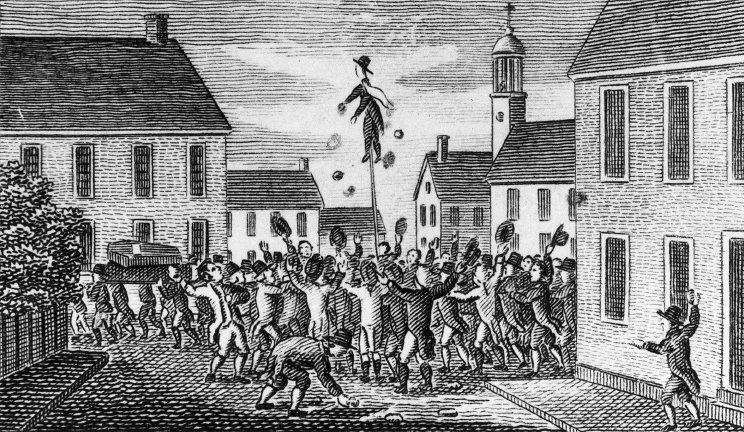

Crowd Actions Popular opposition also took a violent form, however. When the Stamp Act went into effect on November 1, 1765, disciplined mobs demanded the resignation of stamp-tax collectors. In Boston, a group calling itself the Sons of Liberty burned an effigy of collector Andrew Oliver and then destroyed Oliver’s new brick warehouse. Two weeks later, Bostonians attacked the house of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson, Oliver’s brother-in-law and a prominent defender of imperial authority, breaking his furniture, looting his wine cellar, and setting fire to his library.

Wealthy merchants and Patriot lawyers, such as John Hancock and John Adams, encouraged the mobs, which were usually led by middling artisans and minor merchants. In New York City, nearly three thousand shopkeepers, artisans, laborers, and seamen marched through the streets breaking windows and crying “Liberty!” Resistance to the Stamp Act spread far beyond the port cities: in nearly every colony, angry crowds — the “rabble,” their detractors called them — intimidated royal officials. Near Wethersfield, Connecticut, five hundred farmers seized tax collector Jared Ingersoll and forced him to resign his office in “the Cause of the People.”

The Motives of the Crowd Such crowd actions were common in both Britain and America, and protesters had many motives. Roused by the Great Awakening, evangelical Protestants resented arrogant British military officers and corrupt royal bureaucrats. In New England, where rioters invoked the antimonarchy sentiments of their great-grandparents, an anonymous letter sent to a Boston newspaper promising to save “all the Freeborn Sons of America” was signed “Oliver Cromwell,” the English republican revolutionary of the 1650s. In New York City, Sons of Liberty leaders Isaac Sears and Alexander McDougall were minor merchants and Radical Whigs who feared that imperial reform would undermine political liberty. The mobs also included apprentices, day laborers, and unemployed sailors: young men with their own notions of liberty who — especially if they had been drinking — were quick to resort to violence.

Nearly everywhere popular resistance nullified the Stamp Act. Fearing an assault on Fort George, New York lieutenant governor Cadwallader Colden called on General Gage to use his small military force to protect the stamps. Gage refused. “Fire from the Fort might disperse the Mob, but it would not quell them,” he told Colden, and the result would be “an Insurrection, the Commencement of Civil War.” The tax was collected in Barbados and Jamaica, but frightened collectors resigned their offices in all thirteen colonies that would eventually join in the Declaration of Independence. This popular insurrection gave a democratic cast to the emerging Patriot movement. “Nothing is wanting but your own Resolution,” declared a New York rioter, “for great is the Authority and Power of the People.”

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

Why did the Stamp Act arouse so much more resistance than the Sugar Act?