America’s History: Printed Page 160

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 142

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 138

Parliament and Patriots Square Off Again

When news of the Stamp Act riots and the boycott reached Britain, Parliament was already in turmoil. Disputes over domestic policy had led George III to dismiss Grenville as prime minister (Table 5.2). However, Grenville’s allies demanded that imperial reform continue, if necessary at gunpoint. “The British legislature,” declared Chief Justice Sir James Mansfield, “has authority to bind every part and every subject, whether such subjects have a right to vote or not.”

| Ministerial Instability in Britain, 1760–1782 | ||

| Leading Minister | Dates of Ministry | American Policy |

| Lord Bute | 1760–1763 | Mildly reformist |

| George Grenville | 1763–1765 | Ardently reformist |

| Lord Rockingham | 1765–1766 | Accommodationist |

| William Pitt / Charles Townshend | 1766–1770 | Ardently reformist |

| Lord North | 1770–1782 | Coercive |

Yet a majority in Parliament was persuaded that the Stamp Act was cutting deeply into British exports and thus doing more harm than good. “The Avenues of Trade are all shut up,” a Bristol merchant told Parliament: “We have no Remittances and are at our Witts End for want of Money to fulfill our Engagements with our Tradesmen.” Grenville’s successor, the Earl of Rockingham, forged a compromise. To mollify the colonists and help British merchants, he repealed the Stamp Act and reduced the duty on molasses imposed by the Sugar Act to a penny a gallon. Then he pacified imperial reformers and hard-liners with the Declaratory Act of 1766, which explicitly reaffirmed Parliament’s “full power and authority to make laws and statutes … to bind the colonies and people of America … in all cases whatsoever.” By swiftly ending the Stamp Act crisis, Rockingham hoped it would be forgotten just as quickly.

Charles Townshend Steps In Often the course of history is changed by a small event — an illness, a personal grudge, a chance remark. That was the case in 1767, when George III named William Pitt to head a new government. Pitt, chronically ill and often absent from parliamentary debates, left chancellor of the exchequer Charles Townshend in command. Pitt was sympathetic toward America; Townshend was not. As a member of the Board of Trade, Townshend had sought restrictions on the colonial assemblies and strongly supported the Stamp Act. In 1767, he promised to find a new source of revenue in America.

The new tax legislation, the Townshend Act of 1767, had both fiscal and political goals. It imposed duties on colonial imports of paper, paint, glass, and tea that were expected to raise about £40,000 a year. Though Townshend did allocate some of this revenue for American military expenses, he earmarked most of it to pay the salaries of royal governors, judges, and other imperial officials, who had always previously been paid by colonial assemblies. Now, he hoped, royal appointees could better enforce parliamentary laws and carry out the king’s instructions. Townshend next devised the Revenue Act of 1767, which created a board of customs commissioners in Boston and vice-admiralty courts in Halifax, Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston. By using parliamentary taxes to finance imperial administration, Townshend intended to undermine American political institutions.

The Townshend duties revived the constitutional debate over taxation. During the Stamp Act crisis, some Americans, including Benjamin Franklin, distinguished between external and internal taxes. They suggested that external duties on trade (such as those long mandated by the Navigation Acts) were acceptable to Americans, but that direct, or internal, taxes were not. Townshend thought this distinction was “perfect nonsense,” but he indulged the Americans and laid duties only on trade.

A Second Boycott and the Daughters of Liberty Even so, most colonial leaders rejected the legitimacy of Townshend’s measures. In February 1768, the Massachusetts assembly condemned the Townshend Act, and Boston and New York merchants began a new boycott of British goods. Throughout Puritan New England, ministers and public officials discouraged the purchase of “foreign superfluities” and promoted the domestic manufacture of cloth and other necessities.

American women, ordinarily excluded from public affairs, became crucial to the nonimportation movement. They reduced their households’ consumption of imported goods and produced large quantities of homespun cloth. Pious farmwives spun yarn at their ministers’ homes. In Berwick, Maine, “true Daughters of Liberty” celebrated American products by “drinking rye coffee and dining on bear venison.” Other women’s groups supported the boycott with charitable work, spinning flax and wool for the needy. Just as Patriot men followed tradition by joining crowd actions, so women’s protests reflected their customary concern for the well-being of the community.

Newspapers celebrated these exploits of the Daughters of Liberty. One Massachusetts town proudly claimed an annual output of 30,000 yards of cloth; East Hartford, Connecticut, reported 17,000 yards. This surge in domestic production did not offset the loss of British imports, which had averaged about 10 million yards of cloth annually, but it brought thousands of women into the public arena.

The boycott mobilized many American men as well. In the seaport cities, the Sons of Liberty published the names of merchants who imported British goods and harassed their employees and customers. By March 1769, the nonimportation movement had spread to Philadelphia; two months later, the members of the Virginia House of Burgesses vowed not to buy dutied articles, luxury goods, or imported slaves. Reflecting colonial self-confidence, Benjamin Franklin called for a return to the pre-1763 mercantilist system: “Repeal the laws, renounce the right, recall the troops, refund the money, and return to the old method of requisition.”

Despite the enthusiasm of Patriots, nonimportation — accompanied by pressure on merchants and consumers who resisted it — opened fissures in colonial society. Not only royal officials, but also merchants, farmers, and ordinary folk, were subject to new forms of surveillance and coercion — a pattern that would only become more pronounced as the imperial crisis unfolded.

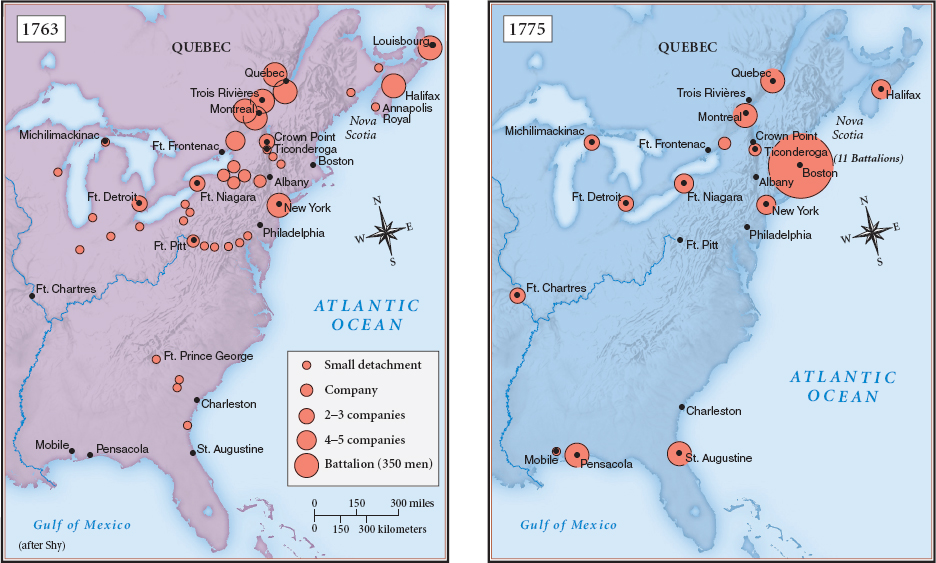

Troops to Boston American resistance only increased British determination. When the Massachusetts assembly’s letter opposing the Townshend duties reached London, Lord Hillsborough, the secretary of state for American affairs, branded it “unjustifiable opposition to the constitutional authority of Parliament.” To strengthen the “Hand of Government” in Massachusetts, Hillsborough dispatched General Thomas Gage and 2,000 British troops to Boston (Map 5.3). Once in Massachusetts, Gage accused its leaders of “Treasonable and desperate Resolves” and advised the ministry to “Quash this Spirit at a Blow.” In 1765, American resistance to the Stamp Act had sparked a parliamentary debate; in 1768, it provoked a plan for military coercion.

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES

Question

How did the nonimportation movement bring women into the political sphere?