America’s History: Printed Page 166

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 146

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 142

Parliament Wavers

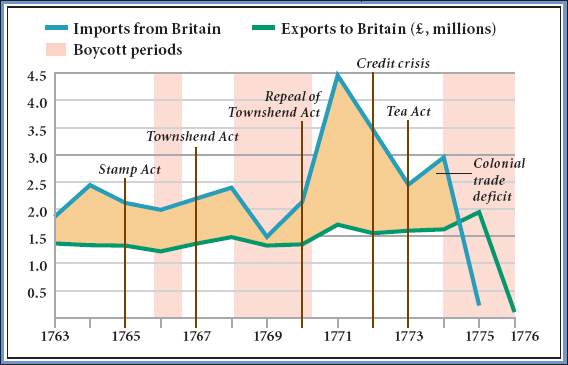

In Britain, the colonies’ nonimportation agreement was taking its toll. In 1768, the colonies had cut imports of British manufactures in half; by 1769, the mainland colonies had a trade surplus with Britain of £816,000. Hard-hit by these developments, British merchants and manufacturers petitioned Parliament to repeal the Townshend duties. Early in 1770, Lord North became prime minister. A witty man and a skillful politician, North designed a new compromise. Arguing that it was foolish to tax British exports to America (thereby raising their price and decreasing consumption), he persuaded Parliament to repeal most of the Townshend duties. However, North retained the tax on tea as a symbol of Parliament’s supremacy (Figure 5.2).

The Boston Massacre Even as Parliament was debating North’s repeal, events in Boston guaranteed that reconciliation between Patriots and Parliament would be hard to achieve. Between 1,200 and 2,000 troops had been stationed in Boston for a year and a half. Soldiers were also stationed in New York, Philadelphia, several towns in New Jersey, and various frontier outposts in these years, with a minimum of conflict or violence. But in Boston — a small port town on a tiny peninsula — the troops numbered 10 percent of the local population, and their presence wore on the locals. On the night of March 5, 1770, a group of nine British redcoats fired into a crowd and killed five townspeople. A subsequent trial exonerated the soldiers, but Boston’s Radical Whigs, convinced of a ministerial conspiracy against liberty, labeled the incident a “massacre” and used it to rally sentiment against imperial power.

Sovereignty Debated When news of North’s compromise arrived in the colonies in the wake of the Boston Massacre, the reaction was mixed. Most of Britain’s colonists remained loyal to the empire, but five years of conflict had taken their toll. In 1765, American leaders had accepted Parliament’s authority; the Stamp Act Resolves had opposed only certain “unconstitutional” legislation. By 1770, the most outspoken Patriots — Benjamin Franklin in Pennsylvania, Patrick Henry in Virginia, and Samuel Adams in Massachusetts — repudiated parliamentary supremacy and claimed equality for the American assemblies within the empire. Franklin suggested that the colonies were now “distinct and separate states” with “the same Head, or Sovereign, the King.”

Franklin’s suggestion outraged Thomas Hutchinson, the American-born royal governor of Massachusetts. Hutchinson emphatically rejected the idea of “two independent legislatures in one and the same state.” He told the Massachusetts assembly, “I know of no line that can be drawn between the supreme authority of Parliament and the total independence of the colonies.”

There the matter rested. The British had twice imposed revenue acts on the colonies, and American Patriots had twice forced a retreat. If Parliament insisted on a policy of constitutional absolutism by imposing taxes a third time, some Americans were prepared to pursue violent resistance. Nor did they flinch when reminded that George III condemned their agitation. As the Massachusetts House replied to Hutchinson, “There is more reason to dread the consequences of absolute uncontrolled supreme power, whether of a nation or a monarch, than those of total independence.” Fearful of civil war, Lord North’s ministry hesitated to force the issue.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

What was Benjamin Franklin’s position on colonial representation in 1765, and why had his view changed by 1770?