America’s History: Printed Page 168

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 148

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 144

A Compromise Repudiated

Once aroused, political passions are not easily quieted. In Boston, Samuel Adams and other radical Patriots continued to warn Americans of imperial domination and, late in 1772, persuaded the town meeting to set up a committee of correspondence “to state the Rights of the Colonists of this Province.” Soon, eighty Massachusetts towns had similar committees. When British officials threatened to seize the Americans responsible for the burning of the customs vessel Gaspée and prosecute them in Britain, the Virginia House of Burgesses and several other assemblies set up their own committees of correspondence. These standing committees allowed Patriots to communicate with leaders in other colonies when new threats to liberty occurred. By 1774, among the colonies that would later declare independence, only Pennsylvania was without one.

The East India Company and the Tea Act These committees sprang into action when Parliament passed the Tea Act of May 1773. The act provided financial relief for the East India Company, a royally chartered private corporation that served as the instrument of British imperialism. The company was deeply in debt; it also had a huge surplus of tea as a result of high import duties, which led Britons and colonists alike to drink smuggled Dutch tea instead. The Tea Act gave the company a government loan and, to boost its revenue, canceled the import duties on tea the company exported to Ireland and the American colonies. Now even with the Townshend duty of 3 pence a pound on tea, high-quality East India Company tea would cost less than the Dutch tea smuggled into the colonies by American merchants.

Radical Patriots accused the British ministry of bribing Americans with the cheaper East India Company’s tea so they would give up their principled opposition to the tea tax. As an anonymous woman wrote to the Massachusetts Spy, “The use of [British] tea is considered not as a private but as a public evil … a handle to introduce a variety of … oppressions amongst us.” Merchants joined the protest because the East India Company planned to distribute its tea directly to shopkeepers, excluding American wholesalers from the trade’s profits. “The fear of an Introduction of a Monopoly in this Country,” British general Frederick Haldimand reported from New York, “has induced the mercantile part of the Inhabitants to be very industrious in opposing this Step and added Strength to a Spirit of Independence already too prevalent.”

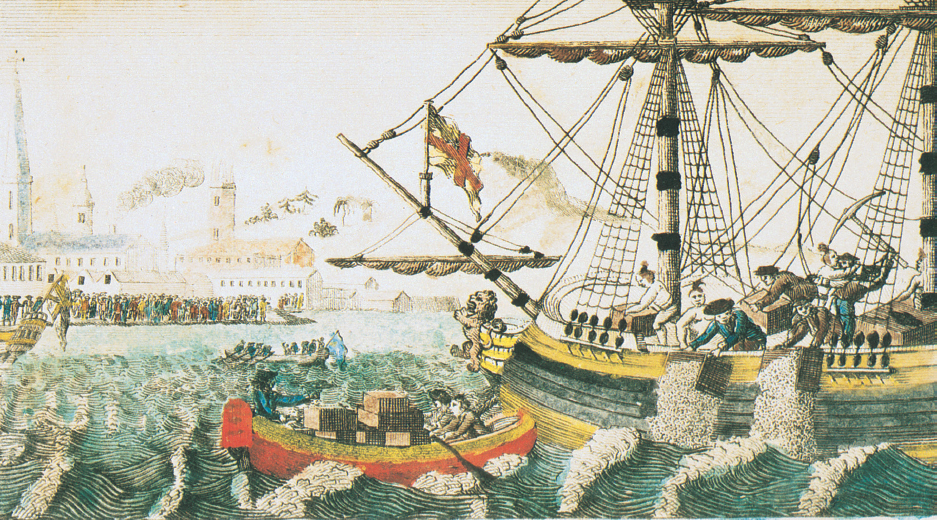

The Tea Party and the Coercive Acts The Sons of Liberty prevented East India Company ships from delivering their cargoes in New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston. In Massachusetts, Royal Governor Hutchinson was determined to land the tea and collect the tax. To foil the governor’s plan, artisans and laborers disguised as Indians boarded three ships — the Dartmouth, the Eleanor, and the Beaver — on December 16, 1773, broke open 342 chests of tea (valued at about £10,000, or about $900,000 today), and threw them into the harbor. “This destruction of the Tea … must have so important Consequences,” John Adams wrote in his diary, “that I cannot but consider it as an Epoch in History.”

The king was outraged. “Concessions have made matters worse,” George III declared. “The time has come for compulsion.” Early in 1774, Parliament passed four Coercive Acts to force Massachusetts to pay for the tea and to submit to imperial authority. The Boston Port Bill closed Boston Harbor to shipping; the Massachusetts Government Act annulled the colony’s charter and prohibited most town meetings; a new Quartering Act mandated new barracks for British troops; and the Justice Act allowed trials for capital crimes to be transferred to other colonies or to Britain.

Patriot leaders throughout the colonies branded the measures “Intolerable” and rallied support for Massachusetts. In Georgia, a Patriot warned the “Freemen of the Province” that “every privilege you at present claim as a birthright, may be wrested from you by the same authority that blockades the town of Boston.” “The cause of Boston,” George Washington declared in Virginia, “now is and ever will be considered as the cause of America.” The committees of correspondence had created a firm sense of Patriot unity.

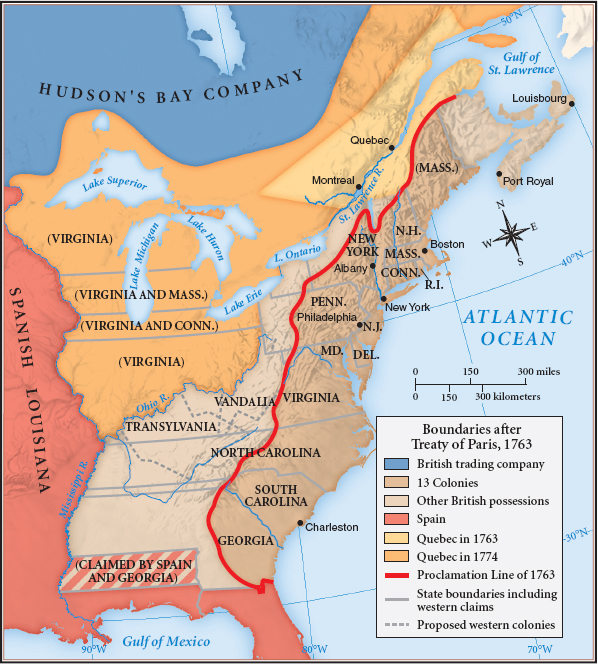

In 1774, Parliament also passed the Quebec Act, which allowed the practice of Roman Catholicism in Quebec. This concession to Quebec’s predominantly Catholic population reignited religious passions in New England, where Protestants associated Catholicism with arbitrary royal government. Because the act extended Quebec’s boundaries into the Ohio River Valley, it likewise angered influential land speculators in Virginia and Pennsylvania and ordinary settlers by the thousands (Map 5.4). Although the ministry did not intend the Quebec Act as a coercive measure, many colonists saw it as further proof of Parliament’s intention to control American affairs.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

Why did colonists react so strongly against the Tea Act, which imposed a small tax and actually lowered the price of tea?