America’s History: Printed Page 152

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 133

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 131

An Empire Transformed

The Great War for Empire of 1756–1763 (Chapter 4) transformed the British Empire in North America. The British ministry could no longer let the colonies manage their own affairs while it contented itself with minimal oversight of the Atlantic trade. Its interests and responsibilities now extended far into the continental interior — a much more costly and complicated proposition than it had ever faced before. And neither its American colonies nor their Native American neighbors were inclined to cooperate in the transformation.

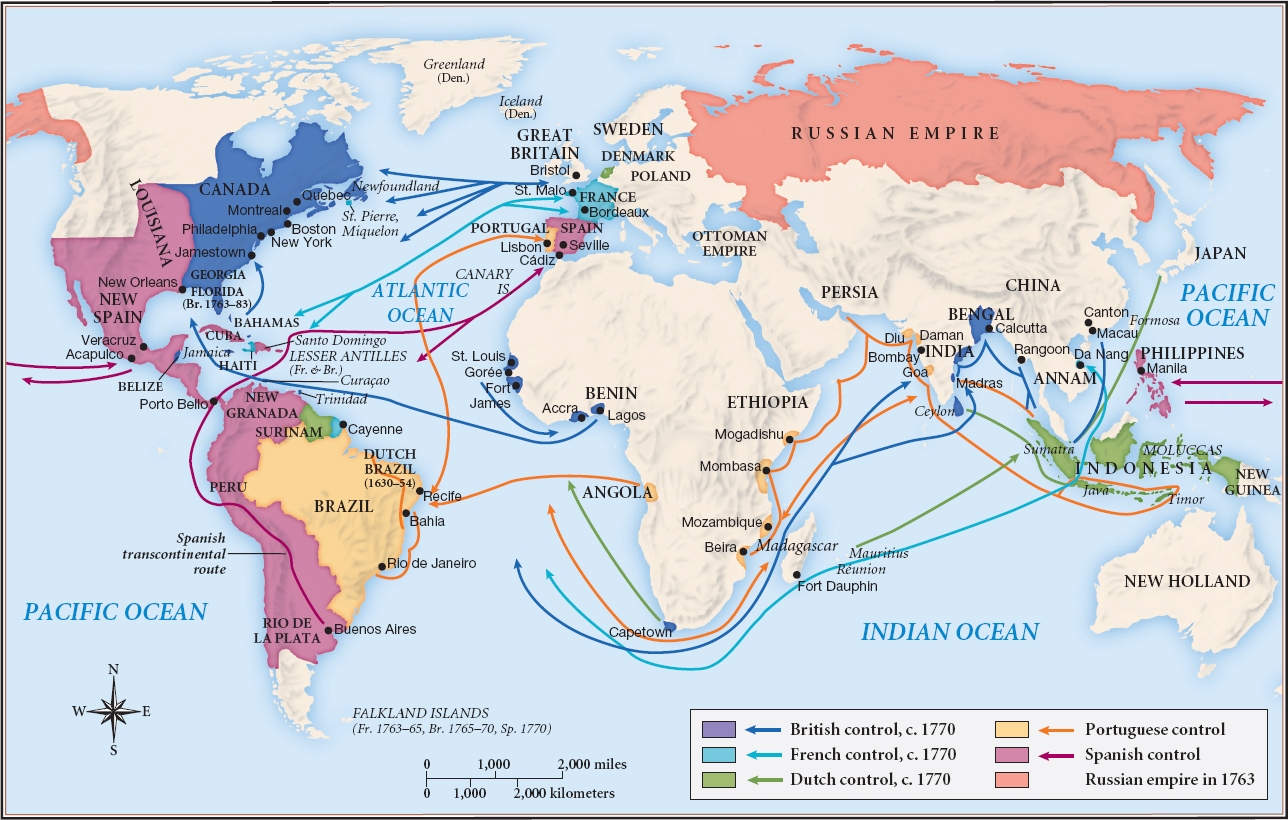

British administrators worried about their American colonists, who, according to former Georgia governor Henry Ellis, felt themselves “entitled to a greater measure of Liberty than is enjoyed by the people of England.” Ireland had been closely ruled for decades, and recently the East India Company set up dominion over millions of non-British peoples (Map 5.1 and America Compared). Britain’s American possessions were likewise filled with aliens and “undesirables”: “French, Dutch, Germans innumerable, Indians, Africans, and a multitude of felons from this country,” as one member of Parliament put it. Consequently, declared Lord Halifax, “The people of England” considered Americans “as foreigners.”

Contesting that status, wealthy Philadelphia lawyer John Dickinson argued that his fellow colonists were “not [East Indian] Sea Poys, nor Marattas, but British subjects who are born to liberty, who know its worth, and who prize it high.” Thus was the stage set for a struggle between the conceptions of identity — and empire — held by British ministers, on the one hand, and many American colonists on the other.