America’s History: Printed Page 152

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 133

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 131

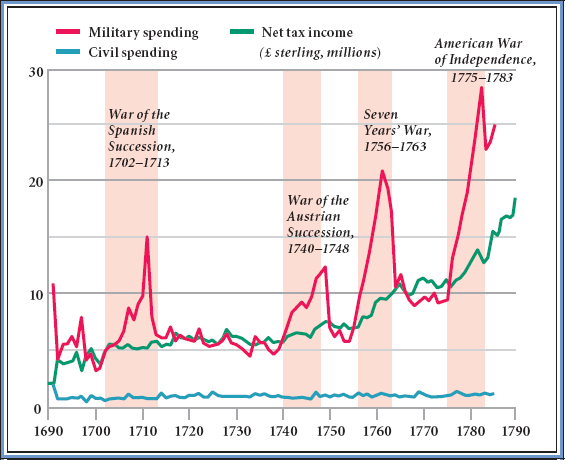

The Costs of Empire

The Great War for Empire imposed enormous costs on Great Britain. The national debt soared from £75 million to £133 million and was, an observer noted, “becoming the alarming object of every British subject.” By war’s end, interest on the debt alone consumed 60 percent of the nation’s budget, and the ministry had to raise taxes. During the eighteenth century, taxes were shifting from land — owned by the gentry and aristocracy — to consumables, and successive ministries became ever more ingenious in devising new ways to raise money. Excise (or sales) taxes were levied on all kinds of ordinary goods — salt and beer, bricks and candles, paper (in the form of a stamp tax) — that were consumed by middling and poor Britons. In the 1760s, the per capita tax burden was 20 percent of income.

To collect the taxes, the government doubled the size of the tax bureaucracy (Figure 5.1). Customs agents patrolled the coasts of southern Britain, seizing tons of contraband French wines, Dutch tea, and Flemish textiles. Convicted smugglers faced heavy penalties, including death or forced “transportation” to America as indentured servants. (Despite colonial protests, nearly fifty thousand English criminals had already been shipped to America to be sold as indentured servants.)

The price of empire abroad was thus larger government and higher taxes at home. Members of two British opposition parties, the Radical Whigs and the Country Party, complained that the huge war debt placed the nation at the mercy of the “monied interests,” the banks and financiers who reaped millions of pounds’ interest from government bonds. To reverse the growth of government and the threat to personal liberty and property rights, British reformers demanded that Parliament represent a broader spectrum of the property-owning classes. The Radical Whig John Wilkes condemned rotten boroughs — sparsely populated, aristocratic-controlled electoral districts — and demanded greater representation for rapidly growing commercial and manufacturing cities. The war thus transformed British politics.

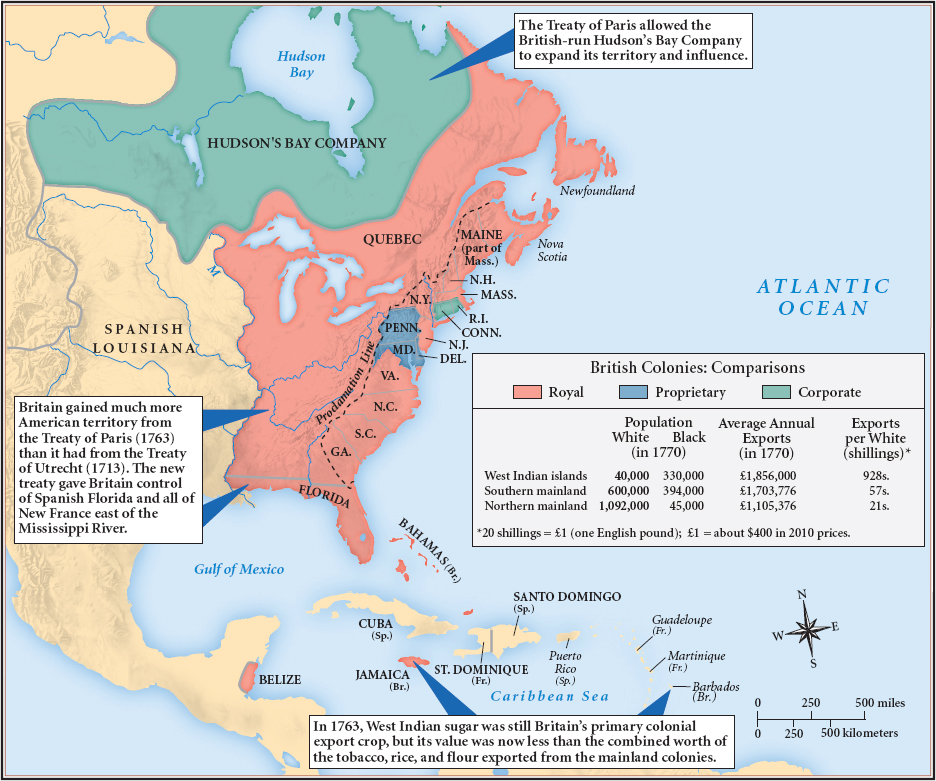

The war also revealed how little power Britain wielded in its American colonies. In theory, royal governors had extensive political powers, including command of the provincial militia; in reality, they shared power with the colonial assemblies, which outraged British officials. The Board of Trade complained that in Massachusetts “almost every act of executive and legislative power is ordered and directed by votes and resolves of the General Court.” To enforce the collection of trade duties, which colonial merchants had evaded for decades by bribing customs officials, Parliament passed the Revenue Act of 1762. The ministry also instructed the Royal Navy to seize American vessels carrying food crops from the mainland colonies to the French West Indies. It was absurd, declared a British politician, that French armies attempting “to Destroy one English province … are actually supported by Bread raised in another.”

Britain’s military victory brought another fundamental shift in policy: a new peacetime deployment of 15 royal battalions — some 7,500 troops — in North America. The ministers who served under George III (r. 1760–1820) feared a possible rebellion by the 60,000 French residents of Canada, Britain’s newly conquered colony (Map 5.2). Native Americans were also a concern: Pontiac’s Rebellion had nearly overwhelmed Britain’s frontier forts. Moreover, only a substantial military force would deter land-hungry whites from defying the Proclamation of 1763 and settling west of the Appalachian Mountains (see Chapter 4). Finally, British politicians worried about the colonists’ loyalty now that they no longer faced a threat from French Canada.

The cost of stationing these troops, estimated at £225,000 per year, compounded Britain’s fiscal crisis, and it seemed clear that the burden had to be shared by the colonies. They had always managed their own finances, but the king’s ministers agreed that Parliament could no longer let them off the hook for the costs of empire. The greatest gains from the war had come in North America, where the specter of French encirclement had finally been lifted, and the greatest new postwar expenses were being incurred in North America as well.

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES

Question

What was the impact of the Great War for Empire on British policymakers and the colonies?