America’s History: Printed Page 196

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 173

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 171

The State Constitutions: How Much Democracy?

In May 1776, the Second Continental Congress urged Americans to reject royal authority and establish republican governments. Most states quickly complied. “Constitutions employ every pen,” an observer noted. Within six months, Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, New Jersey, Delaware, and Pennsylvania had all ratified new constitutions, and Connecticut and Rhode Island had revised their colonial charters to delete references to the king.

Republicanism meant more than ousting the king. The Declaration of Independence stated the principle of popular sovereignty: governments derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed.” In the heat of revolution, many Patriots gave this clause a further democratic twist. In North Carolina, the backcountry farmers of Mecklenburg County told their delegates to the state’s constitutional convention to “oppose everything that leans to aristocracy or power in the hands of the rich.” In Virginia, voters elected a new assembly in 1776 that, an eyewitness remarked, “was composed of men not quite so well dressed, nor so politely educated, nor so highly born” as colonial-era legislatures (Figure 6.1).

|

To see a longer excerpt of the Mecklenburg delegates’ document, along with other primary sources from this period, see Sources for America’s History. |

Pennsylvania’s Controversial Constitution This democratic impulse flowered in Pennsylvania, thanks to a coalition of Scots-Irish farmers, Philadelphia artisans, and Enlightenment-influenced intellectuals. In 1776, these insurgents ousted every officeholder of the Penn family’s proprietary government, abolished property ownership as a qualification for voting, and granted all taxpaying men the right to vote and hold office. The Pennsylvania constitution of 1776 also created a unicameral (one-house) legislature with complete power; there was no governor to exercise a veto. Other provisions mandated a system of elementary education and protected citizens from imprisonment for debt.

Pennsylvania’s democratic constitution alarmed many leading Patriots. From Boston, John Adams denounced the unicameral legislature as “so democratical that it must produce confusion and every evil work.” Along with other conservative Patriots, Adams wanted to restrict office holding to “men of learning, leisure and easy circumstances” and warned of oppression under majority rule: “If you give [ordinary citizens] the command or preponderance in the … legislature, they will vote all property out of the hands of you aristocrats.”

Tempering Democracy To counter the appeal of the Pennsylvania constitution, Adams published Thoughts on Government (1776). In that treatise, he adapted the British Whig theory of mixed government (a sharing of power among the monarch, the House of Lords, and the Commons) to a republican society. To disperse authority and preserve liberty, he insisted on separate institutions: legislatures would make laws, the executive would administer them, and the judiciary would enforce them. Adams also demanded a bicameral (two-house) legislature with an upper house of substantial property owners to offset the popular majorities in the lower one. As further curbs on democracy, he proposed an elected governor with veto power and an appointed — not elected — judiciary.

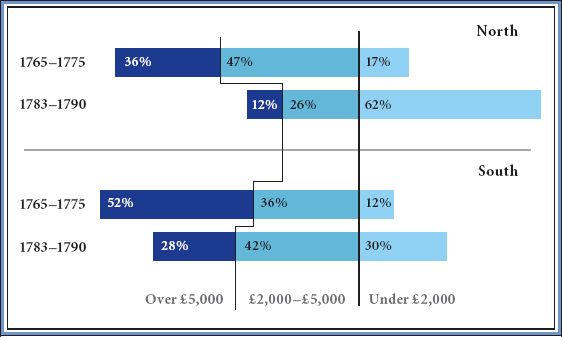

Conservative Patriots endorsed Adams’s governmental system. In New York’s constitution of 1777, property qualifications for voting excluded 20 percent of white men from assembly elections and 60 percent from casting ballots for the governor and the upper house. In South Carolina, elite planters used property rules to disqualify about 90 percent of white men from office holding. The 1778 constitution required candidates for governor to have a debt-free estate of £10,000 (about $700,000 today), senators to be worth £2,000, and assemblymen to own property valued at £1,000. Even in traditionally democratic Massachusetts, the 1780 constitution, authored primarily by Adams, raised property qualifications for voting and office holding and skewed the lower house toward eastern, mercantile interests.

The political legacy of the Revolution was complex. Only in Pennsylvania and Vermont were radical Patriots able to create truly democratic institutions. Yet in all the new states, representative legislatures had acquired more power, and average citizens now had greater power at the polls and greater influence in the halls of government.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

What aspects of the Pennsylvania constitution were most objectionable to Adams, and what did he advocate instead?