America’s History: Printed Page 199

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 176

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 174

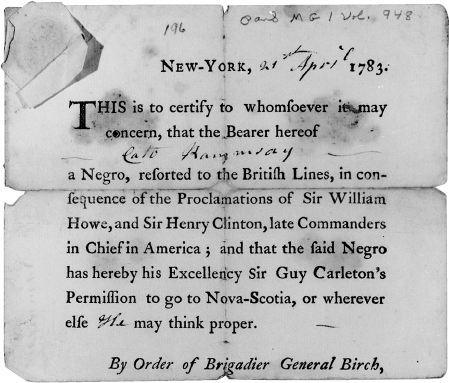

The War’s Losers: Loyalists, Native Americans, and Slaves

The success of republican institutions was assisted by the departure of as many as 100,000 Loyalists, many of whom suffered severe financial losses. Some Patriots demanded revolutionary justice: the seizure of all Loyalist property and its distribution to needy Americans. But most officials were unwilling to go so far. When state governments did seize Loyalist property, they often auctioned it to the highest bidders; only rarely did small-scale farmers benefit. In the cities, Patriot merchants replaced Loyalists at the top of the economic ladder, supplanting a traditional economic elite — who often invested profits from trade in real estate — with republican entrepreneurs who tended to promote new trading ventures and domestic manufacturing. This shift facilitated America’s economic development in the years to come.

Though the Revolution did not result in widespread property redistribution, it did encourage yeomen, middling planters, and small-time entrepreneurs to believe that their new republican governments would protect their property and ensure widespread access to land. In western counties, former Regulators demanded that the new governments be more responsive to their needs; beyond the Appalachians, thousands of squatters who had occupied lands in Kentucky and Tennessee expected their claims to be recognized and lands to be made available on easy terms. If the United States were to secure the loyalty of westerners, it would have to meet their needs more effectively than the British Empire had.

This meant, among other things, extinguishing Native American claims to land as quickly as possible. At war’s end, George Washington commented on the “rage for speculating” in Ohio Valley lands. “Men in these times, talk with as much facility of fifty, a hundred, and even 500,000 Acres as a Gentleman formerly would do of 1000 acres.” “If we make a right use of our natural advantages,” a Fourth of July orator observed, “we soon must be a truly great and happy people.” Native American land claims stood as a conspicuous barrier to the “natural advantages” he imagined.

For southern slaveholders, the Revolution was fought to protect property rights, and any sentiment favoring slave emancipation met with violent objections. When Virginia Methodists called for general emancipation in 1785, slaveholders used Revolutionary principles to defend their right to human property. They “risked [their] Lives and Fortunes, and waded through Seas of Blood” to secure “the Possession of [their] Rights of Liberty and Property,” only to hear of “a very subtle and daring Attempt” to “dispossess us of a very important Part of our Property.” Emancipation would bring “Want, Poverty, Distress, and Ruin to the Free Citizen.” The liberties coveted by ordinary white Americans bore hard on the interests of Native Americans and slaves.

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES

Question

How did the Revolutionary commitment to liberty and the protection of property affect enslaved African Americans and western Indians?