America’s History: Printed Page 207

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 187

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 183

The People Debate Ratification

The procedure for ratifying the new constitution was as controversial as its contents. Knowing that Rhode Island (and perhaps other states) would reject it, the delegates did not submit the Constitution to the state legislatures for their unanimous consent, as required by the Articles of Confederation. Instead, they arbitrarily — and cleverly — declared that it would take effect when ratified by conventions in nine of the thirteen states.

As the constitutional debate began in early 1788, the nationalists seized the initiative with two bold moves. First, they called themselves Federalists, suggesting that they supported a federal union — a loose, decentralized system — and obscuring their commitment to a strong national government. Second, they launched a coordinated campaign in pamphlets and newspapers to explain and justify the Philadelphia constitution.

The Antifederalists The opponents of the Constitution, called by default the Antifederalists, had diverse backgrounds and motives. Some, like Governor George Clinton of New York, feared that state governments would lose power. Rural democrats protested that the proposed document, unlike most state constitutions, lacked a declaration of individual rights; they also feared that the central government would be run by wealthy men. “Lawyers and men of learning and monied men expect to be managers of this Constitution,” worried a Massachusetts farmer. “[T]hey will swallow up all of us little folks … just as the whale swallowed up Jonah.” Giving political substance to these fears, Melancton Smith of New York argued that the large electoral districts prescribed by the Constitution would restrict office holding to wealthy men, whereas the smaller districts used in state elections usually produced legislatures “composed principally of respectable yeomanry.” John Quincy Adams agreed: if only “eight men” would represent Massachusetts, “they will infallibly be chosen from the aristocratic part of the community.”

Smith summed up the views of Americans who held traditional republican values. To keep government “close to the people,” they wanted the states to remain small sovereign republics tied together only for trade and defense — not the “United States” but the “States United.” Citing the French political philosopher Montesquieu, Antifederalists argued that republican institutions were best suited to small polities. “No extensive empire can be governed on republican principles,” declared James Winthrop of Massachusetts. Patrick Henry worried that the Constitution would re-create British rule: high taxes, an oppressive bureaucracy, a standing army, and a “great and mighty President … supported in extravagant munificence.” As another Antifederalist put it, “I had rather be a free citizen of the small republic of Massachusetts than an oppressed subject of the great American empire.”

Federalists Respond In New York, where ratification was hotly contested, James Madison, John Jay, and Alexander Hamilton defended the proposed constitution in a series of eighty-five essays written in 1787 and 1788, collectively titled The Federalist. This work influenced political leaders throughout the country and subsequently won acclaim as an important treatise of practical republicanism. Its authors denied that a centralized government would lead to domestic tyranny. Drawing on Montesquieu’s theories and John Adams’s Thoughts on Government, Madison, Jay, and Hamilton pointed out that authority would be divided among the president, a bicameral legislature, and a judiciary. Each branch of government would “check and balance” the others and so preserve liberty.

In “Federalist No. 10,” Madison challenged the view that republican governments only worked in small polities, arguing that a large state would better protect republican liberty. It was “sown in the nature of man,” Madison wrote, for individuals to seek power and form factions. Indeed, “a landed interest, a manufacturing interest, a mercantile interest, a moneyed interest, with many lesser interests, grow up of necessity in civilized nations.” A free society should welcome all factions but keep any one of them from becoming dominant — something best achieved in a large republic. “Extend the sphere and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests,” Madison concluded, inhibiting the formation of a majority eager “to invade the rights of other citizens.”

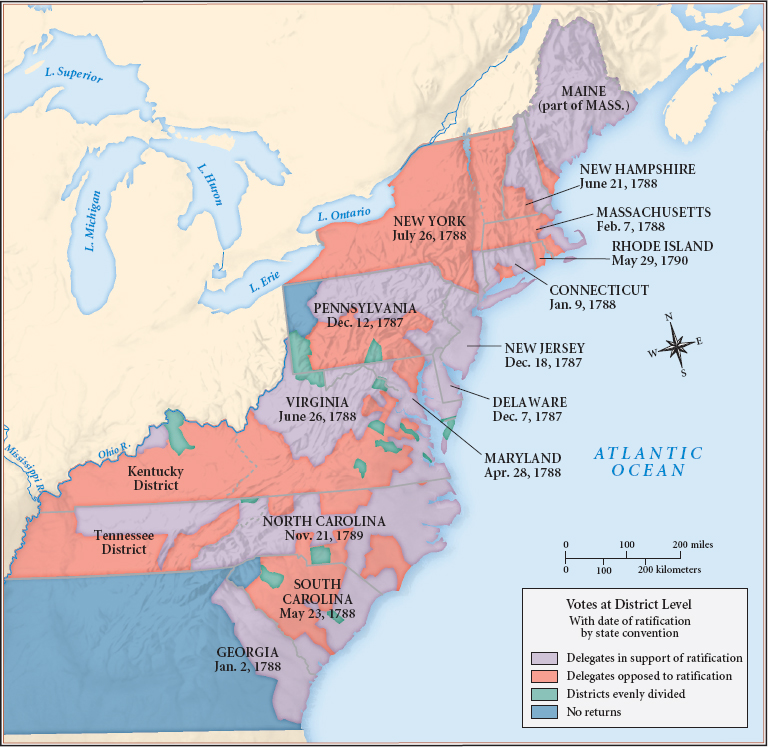

The Constitution Ratified The delegates debating these issues in the state ratification conventions included untutored farmers and middling artisans as well as educated gentlemen. Generally, backcountry delegates were Antifederalists, while those from coastal areas were Federalists. In Pennsylvania, Philadelphia merchants and artisans joined commercial farmers to ratify the Constitution. Other early Federalist successes came in four less populous states — Delaware, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut — where delegates hoped that a strong national government would offset the power of large neighboring states (Map 6.7).

The Constitution’s first real test came in January 1788 in Massachusetts, a hotbed of Antifederalist sentiment. Influential Patriots, including Samuel Adams and Governor John Hancock, opposed the new constitution, as did many followers of Daniel Shays. But Boston artisans, who wanted tariff protection from British imports, supported ratification. To win over other delegates, Federalist leaders assured the convention that they would recommend a national bill of rights. By a close vote of 187 to 168, the Federalists carried the day.

Spring brought Federalist victories in Maryland, South Carolina, and New Hampshire, reaching the nine-state quota required for ratification. But it took the powerful arguments advanced in The Federalist and more promises of a bill of rights to secure the Constitution’s adoption in the essential states of Virginia and New York. The votes were again close: 89 to 79 in Virginia and 30 to 27 in New York.

Testifying to their respect for popular sovereignty and majority rule, most Americans accepted the verdict of the ratifying conventions. “A decided majority” of the New Hampshire assembly had opposed the “new system,” reported Joshua Atherton, but now they said, “It is adopted, let us try it.” In Virginia, Patrick Henry vowed to “submit as a quiet citizen” and fight for amendments “in a constitutional way.”

Unlike in France, where the Revolution of 1789 divided the society into irreconcilable factions for generations, the American Constitutional Revolution of 1787 created a national republic that enjoyed broad popular support. Federalists celebrated their triumph by organizing great processions in the seaport cities. By marching in an orderly fashion — in conscious contrast to the riotous Revolutionary mobs — Federalist-minded citizens affirmed their allegiance to a self-governing but elite-ruled republican nation.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

How did the Constitution, in its final form, differ from the plan that James Madison originally proposed?