America’s History: Printed Page 223

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 199

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 195

The Rise of Political Parties

The appearance of Federalists and Republicans marked a new stage in American politics — what historians call the First Party System. Colonial legislatures had factions based on family, ethnicity, or region, but they did not have organized political parties. Nor did the new state and national constitutions make any provision for political societies. Indeed, most Americans believed that parties were dangerous because they looked out for themselves rather than serving the public interest.

But a shared understanding of the public interest collapsed in the face of sharp conflicts over Hamilton’s fiscal policies. Most merchants and creditors supported the Federalist Party, as did wheat-exporting slaveholders in the Tidewater districts of the Chesapeake. The emerging Republican coalition included southern tobacco and rice planters, debt-conscious western farmers, Germans and Scots-Irish in the southern backcountry, and subsistence farmers in the Northeast.

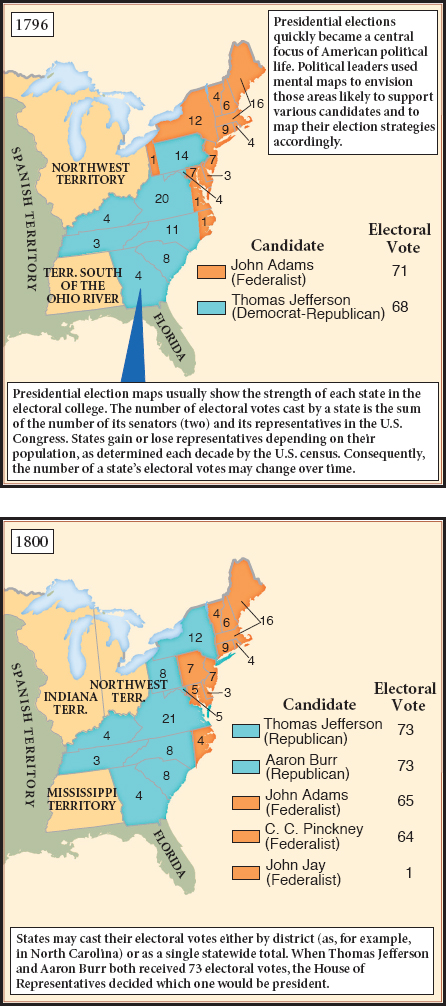

Party identity crystallized in 1796. To prepare for the presidential election, Federalist and Republican leaders called caucuses in Congress and conventions in the states. They also mobilized popular support by organizing public festivals and processions: the Federalists held banquets in February to celebrate Washington’s birthday, and the Republicans marched through the streets on July 4 to honor the Declaration of Independence.

In the election, voters gave Federalists a majority in Congress and made John Adams president. Adams continued Hamilton’s pro-British foreign policy and strongly criticized French seizures of American merchant ships. When the French foreign minister Talleyrand solicited a loan and a bribe from American diplomats to stop the seizures, Adams charged that Talleyrand’s agents, whom he dubbed X, Y, and Z, had insulted America’s honor. In response to the XYZ Affair, Congress cut off trade with France in 1798 and authorized American privateering (licensing private ships to seize French vessels). This undeclared maritime war curtailed American trade with the French West Indies and resulted in the capture of nearly two hundred French and American merchant vessels.

The Naturalization, Alien, and Sedition Acts of 1798 As Federalists became more hostile to the French Republic, they also took a harder line against their Republican critics. When Republican-minded immigrants from Ireland vehemently attacked Adams’s policies, a Federalist pamphleteer responded in kind: “Were I president, I would hang them for otherwise they would murder me.” To silence the critics, the Federalists enacted three coercive laws limiting individual rights and threatening the fledgling party system. The Naturalization Act lengthened the residency requirement for American citizenship from five to fourteen years, the Alien Act authorized the deportation of foreigners, and the Sedition Act prohibited the publication of insults or malicious attacks on the president or members of Congress. “He that is not for us is against us,” thundered the Federalist Gazette of the United States. Using the Sedition Act, Federalist prosecutors arrested more than twenty Republican newspaper editors and politicians, accused them of sedition, and convicted and jailed a number of them.

This repression sparked a constitutional crisis. Republicans charged that the Sedition Act violated the First Amendment’s prohibition against “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” However, they did not appeal to the Supreme Court because the Court’s power to review congressional legislation was uncertain and because most of the justices were Federalists. Instead, Madison and Jefferson looked to the state legislatures. At their urging, the Kentucky and Virginia legislatures issued resolutions in 1798 declaring the Alien and Sedition Acts to be “unauthoritative, void, and of no force.” The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions set forth a states’ rights interpretation of the Constitution, asserting that the states had a “right to judge” the legitimacy of national laws.

The conflict over the Sedition Act set the stage for the presidential election of 1800. Jefferson, once opposed on principle to political parties, now asserted that they could “watch and relate to the people” the activities of an oppressive government. Meanwhile, John Adams reevaluated his foreign policy. Rejecting Hamilton’s advice to declare war against France (and benefit from the resulting upsurge in patriotism), Adams put country ahead of party and used diplomacy to end the maritime conflict.

The “Revolution of 1800” The campaign of 1800 degenerated into a bitter, no-holds-barred contest. The Federalists launched personal attacks on Jefferson, branding him an irresponsible pro-French radical and, because he opposed state support of religion in Virginia, “the arch-apostle of irreligion and free thought.” Both parties changed state election laws to favor their candidates, and rumors circulated of a Federalist plot to stage a military coup.

The election did not end these worries. Thanks to a low Federalist turnout in Virginia and Pennsylvania and the three-fifths rule (which boosted electoral votes in the southern states), Jefferson won a narrow 73-to-65 victory over Adams in the electoral college. However, the Republican electors also gave 73 votes to Aaron Burr of New York, who was Jefferson’s vice-presidential running mate (Map 7.1). The Constitution specified that in the case of a tie vote, the House of Representatives would choose between the candidates. For thirty-five rounds of balloting, Federalists in the House blocked Jefferson’s election, prompting rumors that Virginia would raise a military force to put him into office.

Ironically, arch-Federalist Alexander Hamilton ushered in a more democratic era by supporting Jefferson. Calling Burr an “embryo Caesar” and the “most unfit man in the United States for the office of president,” Hamilton persuaded key Federalists to allow Jefferson’s election. The Federalists’ concern for political stability also played a role. As Senator James Bayard of Delaware explained, “It was admitted on all hands that we must risk the Constitution and a Civil War or take Mr. Jefferson.”

Jefferson called the election the “Revolution of 1800,” and so it was. The bloodless transfer of power showed that popularly elected governments could be changed in an orderly way, even in times of bitter partisan conflict. In his inaugural address in 1801, Jefferson praised this achievement, declaring, “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.”

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

Why did Jefferson consider his election in 1800 to be revolutionary?