America’s History: Printed Page 228

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 206

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 201

Migration and the Changing Farm Economy

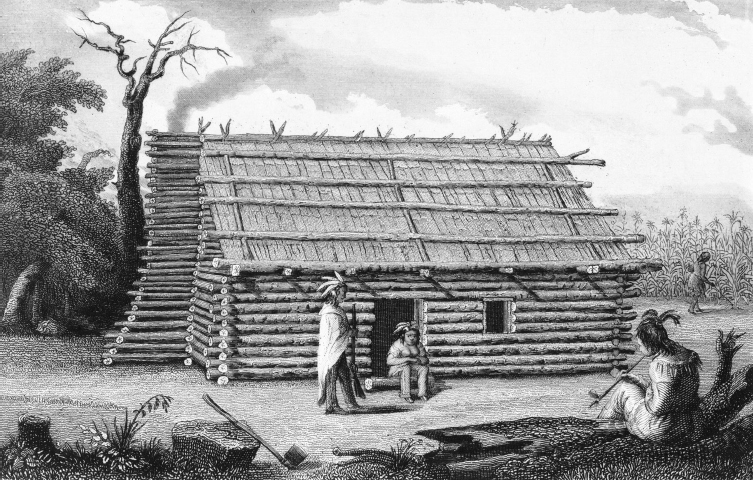

Native American resistance slowed the advance of white settlers but did not stop it. Nothing “short of a Chinese Wall, or a line of Troops,” Washington declared, “will restrain … the Incroachment of Settlers, upon the Indian Territory.” During the 1790s, two great streams of migrants moved out of the southern states (Map 7.3).

Southern Migrants One stream, composed primarily of white tenant farmers and struggling yeomen families, flocked through the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky and Tennessee. “Boundless settlements open a door for our citizens to run off and leave us,” a worried Maryland landlord lamented, “depreciating all our landed property and disabling us from paying taxes.” In fact, many migrants were fleeing from this planter-controlled society. They wanted more freedom and hoped to prosper by growing cotton and hemp, which were in great demand.

Many settlers in Kentucky and Tennessee lacked ready cash to buy land. Like the North Carolina Regulators in the 1770s, poorer migrants claimed a customary right to occupy “back waste vacant Lands” sufficient “to provide a subsistence to themselves and their Posterity.” Virginia legislators, who administered the Kentucky Territory, had a more elitist vision. Although they allowed poor settlers to buy up to 1,400 acres of land at reduced prices, they sold or granted huge tracts of 100,000 acres to twenty-one groups of speculators and leading men. In 1792, this landed elite owned one-fourth of the state, while half the white men owned no land and lived as quasi-legal squatters or tenant farmers.

Widespread landlessness — and opposition to slavery — prompted a new migration across the Ohio River into the future states of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. In a free community, thought Peter Cartwright, a Methodist lay preacher from southwestern Kentucky who moved to Illinois, “I would be entirely clear of the evil of slavery … [and] could raise my children to work where work was not thought a degradation.” Yet land distribution in Ohio was almost exactly as unequal as in Kentucky: in 1810, a quarter of its real estate was owned by 1 percent of the population, while more than half of its white men were landless.

Meanwhile, a second stream of southern planters and slaves from the Carolinas moved along the coastal plain toward the Gulf of Mexico. Some set up new estates in the interior of Georgia and South Carolina, while others moved into the future states of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. “The Alabama Feaver rages here with great violence,” a North Carolina planter remarked, “and has carried off vast numbers of our Citizens.”

Cotton was the key to this migratory surge. Around 1750, the demand for raw wool and cotton increased dramatically as water-powered spinning jennies, weaving mules, and other technological innovations of the Industrial Revolution boosted textile production in England. South Carolina and Georgia planters began growing cotton, and American inventors, including Connecticut-born Eli Whitney, built machines (called gins) that efficiently extracted seeds from its strands. To grow more cotton, white planters imported about 115,000 Africans between 1776 and 1808, when Congress cut off the Atlantic slave trade. The cotton boom financed the rapid settlement of Mississippi and Alabama — in a single year, a government land office in Huntsville, Alabama, sold $7 million of uncleared land — and the two states entered the Union in 1817 and 1819, respectively.

Exodus from New England As southerners moved across the Appalachians and along the Gulf Coast, a third stream of migrants flowed out of the overcrowded communities of New England. Previous generations of Massachusetts and Connecticut farm families had moved north and east, settling New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine. Now New England farmers moved west. Seeking land for their children, thousands of parents migrated to New York. “The town of Herkimer,” noted one traveler, “is entirely populated by families come from Connecticut.” By 1820, almost 800,000 New Englanders lived in a string of settlements stretching from Albany to Buffalo, and many others had traveled on to Ohio and Indiana. Soon, much of the Northwest Territory consisted of New England communities that had moved inland.

In New York, as in Kentucky and Ohio, well-connected speculators snapped up much of the best land, leasing farms to tenants for a fee. Imbued with the “homestead” ethic, many New England families preferred to buy farms. They signed contracts with the Holland Land Company, a Dutch-owned syndicate of speculators, that allowed settlers to pay for their farms as they worked them, or moved west again in an elusive search for land on easy terms.

Innovation on Eastern Farms The new farm economy in New York, Ohio, and Kentucky forced major changes in eastern agriculture. Unable to compete with lower-priced western grains, farmers in New England switched to potatoes, which were high yielding and nutritious. To make up for the labor of sons and daughters who had moved inland, Middle Atlantic farmers bought more efficient farm equipment. They replaced metal-tipped wooden plows with cast-iron models that dug deeper and required a single yoke of oxen instead of two. Such changes in crop mix and technology kept production high.

Easterners also adopted the progressive farming methods touted by British agricultural reformers. “Improvers” in Pennsylvania doubled their average yield per acre by rotating their crops. Yeomen farmers raised sheep and sold the wool to textile manufacturers. Many farmers adopted a year-round planting cycle, sowing corn in the spring for animal fodder and then planting winter wheat in September for market sale. Women and girls milked the family cows and made butter and cheese to sell in the growing towns and cities.

Whether hacking fields out of western forests or carting manure to replenish eastern soils, farmers now worked harder and longer, but their increased productivity brought them a better standard of living. European demand for American produce was high in these years, and westward migration — the settlement and exploitation of Indian lands — boosted the farming economy throughout the country.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

Why were westward migration and agricultural improvement so widespread in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries?